Landslide classification

Various scientific disciplines have developed taxonomic classification systems to describe natural phenomena or individuals, like for example, plants or animals.

In the following write-up, factors are discussed by dividing them into two groups: the first one is made up of the criteria utilised in the most widespread classification systems that can generally be easily determined.

Furthermore, the evaluation of the age of the landslide permits to correlate the trigger to specific conditions, as earthquakes or periods of intense rains.

It is possible that phenomena could be occurred in past geological times, under specific environmental conditions which no longer act as agents today.

As the landslide is a geological volume with a hidden side, morphological characteristics are extremely important in the reconstruction of the technical model.

Structural and geological factors, as already described, can determine the development of the movement, inducing the presence of mass in kinematic freedom.

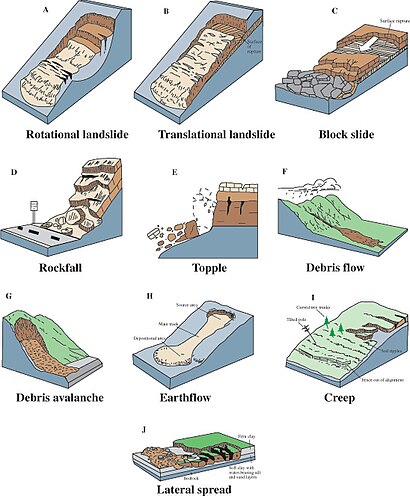

In traditional usage, the term landslide has at one time or another been used to cover almost all forms of mass movement of rocks and regolith at the Earth's surface.

In 1978, in a very highly cited publication, David Varnes noted this imprecise usage and proposed a new, much tighter scheme for the classification of mass movements and subsidence processes.

Toppling is sometimes driven by gravity exerted by material upslope of the displaced mass and sometimes by water or ice in cracks in the mass" (Varnes, 1996) Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid Type of slope: slope angle 45–90 degrees Control factor: Discontinuities, lithostratigraphy Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion "A slide is a downslope movement of soil or rock mass occurring dominantly on the surface of rupture or on relatively thin zones of intense shear strain."

(Varnes, 1996) Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid (>5 m/s) Type of slope: slope angle 20–45 degrees Control factor: Discontinuities, geological setting Description: "Rotational slides move along a surface of rupture that is curved and concave" (Varnes, 1996) Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid Type of slope: slope angle 20–40 degrees[5] Control factor: morphology and lithology Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion "Spread is defined as an extension of a cohesive soil or rock mass combined with a general subsidence of the fractured mass of cohesive material into softer underlying material."

"In spread, the dominant mode of movement is lateral extension accommodated by shear or tensile fractures" (Varnes, 1978) Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid (>5 m/s) Type of slope: angle 45–90 degrees Control factor: Discontinuities, lithostratigraphy Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion A flow is a spatially continuous movement in which surfaces of shear are short-lived, closely spaced, and usually not preserved.

In July 2003 an intense rain band associated with the annual Asian monsoon tracked across central Nepal, triggering 14 fatal landslides that killed 85 people.

Finally, landslides triggered by Hurricane Mitch in 1998 killed an estimated 18,000 people in Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador.

In addition, in some cases fluid pressures can act down the slope as a result of groundwater flow to provide a hydraulic push to the landslide that further decreases the stability.

In some situations, the presence of high levels of fluid may destabilise the slope through other mechanisms, such as: Considerable efforts have been made to understand the triggers for landsliding in natural systems, with quite variable results.

Rafi Ahmad, working in Jamaica, found that for rainfall of short duration (about 1 hour) intensities of greater than 36 mm/h were required to trigger landslides.

Corominas and Moya (1999) found that the following thresholds exist for the upper basin of the Llobregat River, Eastern Pyrenees area.

Without antecedent rainfall, high intensity and short duration rains triggered debris flows and shallow slides developed in colluvium and weathered rocks.

With antecedent rain, moderate intensity precipitation of at least 40 mm in 24 h reactivated mudslides and both rotational and translational slides affecting clayey and silty-clayey formations.

Landslides occur during earthquakes as a result of two separate but interconnected processes: seismic shaking and pore water pressure generation.

The passage of the earthquake waves through the rock and soil produces a complex set of accelerations that effectively act to change the gravitational load on the slope.

These processes can be much more serious in mountainous areas in which the seismic waves interact with the terrain to produce increases in the magnitude of the ground accelerations.

Alternatively, the increase in pore pressure can reduce the normal stress in the slope, allowing the activation of translational and rotational failures.

These can occur either in association with the eruption of the volcano itself, or as a result of mobilisation of the very weak deposits that are formed as a consequence of volcanic activity.

Essentially, there are two main types of volcanic landslide: lahars and debris avalanches, the largest of which are sometimes termed sector collapses.

For example, a part of the side of Casita Volcano in Nicaragua collapsed on October 30, 1998, during the heavy precipitation associated with the passage of Hurricane Mitch.

Debris from the initial small failure eroded older deposits from the volcano and incorporated additional water and wet sediment from along its path, increasing in volume about ninefold.

Debris avalanches commonly occur at the same time as an eruption, but occasionally they may be triggered by other factors such as a seismic shock or heavy rainfall.

The bulge and surrounding area slid away in a gigantic rockslide and debris avalanche, releasing pressure, and triggering a major pumice and ash eruption of the volcano.

The most famous example of this is the Vajont failure, when a rapid decline in lake level contributed to the occurrence of a landslide that killed over 2000 people.