Colombian conflict

[66] Although the deal was rejected in the subsequent October plebiscite,[67] the same month, the then Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to bring the country's more than 50-year-long civil war to an end.

Unlike the rural FARC, which had roots in the previous Liberal peasant struggles, the ELN was mostly an outgrowth of university unrest and would subsequently tend to follow a small group of charismatic leaders, including Camilo Torres Restrepo.

These efforts were aided by the U.S. government and the CIA, which employed hunter-killer teams and involved U.S. personnel from the previous Philippine campaign against the Huks, and which would later participate in the subsequent Phoenix Program in the Vietnam War.

The M-19 was a mostly urban guerrilla group, founded in response to an alleged electoral fraud during the final National Front election of Misael Pastrana Borrero (1970–1974) and the forced removal of former President Gustavo Rojas Pinilla.

[107] By 1982, the perceived passivity of the FARC, together with the relative success of the government's efforts against the M-19 and the ELN, enabled the administration of the Liberal Party's Julio César Turbay Ayala (1978–82) to lift a state-of-siege decree that had been in effect, on and off, for most of the previous 30 years.

The M-19 claimed that the cease-fire had not been fully respected by official security forces, alleged that several of its members had suffered threats and assaults, and questioned the government's real willingness to implement any accords.

[citation needed] According to historian Daniel Pecáut, the creation of the Patriotic Union took the guerrillas' political message to a wider public outside of the traditional communist spheres of influence and led to local electoral victories in regions such as Urabá and Antioquia, with their mayoral candidates winning 23 municipalities and their congressional ones gaining 14 seats (five in the Senate, nine in the lower Chamber) in 1988.

[108] According to journalist Steven Dudley, who interviewed ex-FARC as well as former members of the UP and the Communist Party,[109] FARC leader Jacobo Arenas insisted to his subordinates that the UP's creation did not mean that the group would lay down its arms; neither did it imply a rejection of the Seventh Conference's military strategy.

[112][113] According to Pecáut, the killers included members of the military and the political class who had opposed Betancur's peace process and considered the UP to be little more than a "facade" for the FARC, as well as drug traffickers and landowners who were also involved in the establishment of paramilitary groups.

[114] The Virgilio Barco Vargas (1986–1990) administration, in addition to continuing to handle the difficulties of the complex negotiations with the guerrillas, also inherited a particularly chaotic confrontation against the drug lords, who were engaged in a campaign of terrorism and murder in response to government moves in favor of their extradition overseas.

[115][116] According to journalist Steven Dudley, FARC founder Jacobo Arenas considered the incident to be a "natural" part of the truce and reiterated the group's intention to continue the dialogue, but President Barco sent an ultimatum to the guerrillas and demanded that they immediately disarm or face military retaliation.

[117] Pecáut and Dudley argue that significant tensions had emerged between Jaramillo, FARC and the Communist Party due to the candidate's recent criticism of the armed struggle and their debates over the rebels' use of kidnapping, almost leading to a formal break.

[citation needed] Both parties nevertheless never completely broke off some amount of political contacts for long, as some peace feelers continued to exist, leading to short rounds of conversations in both Caracas, Venezuela (1991) and Tlaxcala, Mexico (1992).

[citation needed] In mid-1996, a civic protest movement made up of an estimated 200,000 coca growers from Putumayo and part of Cauca began marching against the Colombian government to reject its drug war policies, including fumigations and the declaration of special security zones in some departments.

[123][124][125] In Las Delicias, Caquetá, five FARC fronts (about 400 guerrillas) recognized intelligence pitfalls in a Colombian Army base and exploited them to overrun it on August 30, 1996, killing 34 soldiers, wounding 17 and taking some 60 as prisoners.

[citation needed] These attacks, and the dozens of members of the Colombian security forces taken prisoner by the FARC, contributed to increasingly shaming the government of President Ernesto Samper Pizano (1994–1998) in the eyes of sectors of public and political opinion.

[citation needed] Samper also contacted the guerrillas to negotiate the release of some or all of the hostages in FARC hands, which led to the temporary demilitarization of the municipality of Cartagena del Chairá, Caquetá in July 1997 and the unilateral liberation of 70 soldiers, a move which was opposed by the command of the Colombian military.

After some of these operations, government prosecutors and/or human rights organizations blamed officers and members of Colombian Army and police units for either passively permitting these acts, or directly collaborating in their execution.

The new president's program was based on a commitment to bring about a peaceful resolution of Colombia's longstanding civil conflict and to cooperate fully with the United States to combat the trafficking of illegal drugs.

[citation needed] Some critical observers considered that Uribe's policies, while reducing crime and guerrilla activity, were too slanted in favor of a military solution to Colombia's internal war while neglecting grave social and human rights concerns.

Critics have asked for Uribe's government to change this position and make serious efforts towards improving the human rights situation inside the country, protecting civilians and reducing any abuses committed by the armed forces.

[citation needed] In 2001 the largest government supported paramilitary group, the AUC, which had been linked to drug trafficking and attacks on civilians, was added to the US State Department's list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations and the European Union and Canada soon followed suit.

[70] In September 2019, Colombia's President Iván Duque Márquez launched a new military crackdown against FARC, which declared resuming the armed struggle due to the government's failure to abide by the 2016 peace deal.

[185] On April 25, senior Gulf Cartel (Clan de Golfo) leader Gustavo Adolfo Álvarez Téllez, who was one of Colombia's most wanted drug lords, with a 580 million peso bounty for his capture, was arrested at his lavish estate in Cereté while holding a party under quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[189] The Gulf Clan, which dispatched 1,000 of its paramilitaries from Urabá, southern Córdoba and Chocó, hopes to suppress FARC rebels in northern Antioquia and take control of the entire municipality of Ituango.

[200] A study carried out by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) for the year 2001 "[...] shows that Colombia ranked 24th in the countries with the largest participation in military spending, out of a total of 116 investigated.

A study by Corporación Invertir en Colombia (Coinvertir) and the National Planning Department (DNP) shows that insecurity hinders the development of new foreign investments, especially in the financial, oil and gas, and electric power sectors.

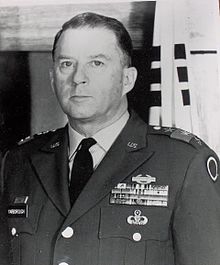

[227] In a secret supplement to his report to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Yarborough encouraged the creation and deployment of a paramilitary force to commit sabotage and terrorist acts against communists: A concerted country team effort should be made now to select civilian and military personnel for clandestine training in resistance operations in case they are needed later.

[51] In 2016, Judge Kenneth Marra of the Southern District of Florida ruled in favor of allowing Colombians to sue former Chiquita Brand International executives for the company's funding of the outlawed right-wing paramilitary organization that murdered their family members.

[241] The Special Jurisdiction of Peace (Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, JEP) would be the transitional justice component of the Comprehensive System, complying with Colombia's duty to investigate, clarify, prosecute and punish serious human rights violations and grave breaches of international humanitarian law which occurred during the armed conflict.