Color motion picture film

These early systems used black-and-white film to photograph and project two or more component images through different color filters.

These also used black-and-white film to photograph multiple color-filtered source images, but the final product was a multicolored print that did not require special projection equipment.

George Méliès offered manual-painted prints of his own films at an additional cost over the black-and-white versions, including the visual-effects pioneering A Trip to the Moon (1902).

[4] The first commercially successful stencil color process was introduced in 1905 by Segundo de Chomón working for Pathé Frères.

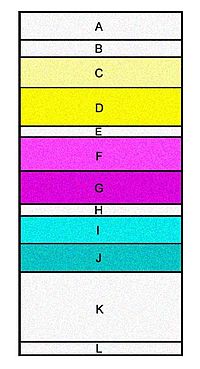

This process was popular during the silent era, with specific colors employed for certain narrative effects (red for scenes with fire or firelight, blue for night, etc.).

[4] A complementary process, called toning, replaces the silver particles in the film with metallic salts or mordanted dyes.

[4] In the United States, St. Louis engraver Max Handschiegl and cinematographer Alvin Wyckoff created the Handschiegl Color Process, a dye-transfer equivalent of the stencil process, first used in Joan the Woman (1917) directed by Cecil B. DeMille, and used in special effects sequences for films such as The Phantom of the Opera (1925).

The Sonochrome line featured films tinted in seventeen different colors including Peachblow, Inferno, Candle Flame, Sunshine, Purple Haze, Firelight, Azure, Nocturne, Verdante, Aquagreen,[6] Caprice, Fleur de Lis, Rose Doree, and the neutral-density Argent, which kept the screen from becoming excessively bright when switching to a black-and-white scene.

Tinting was used as late as 1951 for Sam Newfield's sci-fi film Lost Continent for the green lost-world sequences.

[7] These principles on which color photography is based were first proposed by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1855 and presented at the Royal Society in London in 1861.

Maxwell discovered that all natural colors in this spectrum as perceived by the human eye may be reproduced with additive combinations of three primary colors—red, green, and blue—which, when mixed equally, produce white light.

[8] The film industry recognizes the impact of color on human psychology as it plays a key role in filmmaking by creating the right mood, directing attention, and evoking certain emotions from the audience.

[9] It used a rotating set of red, green and blue filters to photograph the three color components one after the other on three successive frames of panchromatic black-and-white film.

In 1902, Turner shot test footage to demonstrate his system, but projecting it proved problematic because of the accurate registration (alignment) of the three separate color elements required for acceptable results.

[5] This was a two-color system created in England by George Albert Smith, and commercialized by film pioneer Charles Urban's Natural Color Kinematograph Company from 1909 on.

A perceived range of colors resulted from the blending of the separate red and green alternating images by the viewer's persistence of vision.

[4] The first practical subtractive color process was introduced by Kodak as "Kodachrome", a name recycled twenty years later for a very different and far better-known product.

Leon Forrest Douglass (1869–1940), a founder of Victor Records, developed a system he called Naturalcolor, and first showed a short test film made in the process on 15 May 1917 at his home in San Rafael, California.

The system used a beam splitter in a specially modified camera to send red and green light to adjacent frames of one strip of black-and-white film.

From this negative, skip-printing was used to print each color's frames contiguously onto film stock with half the normal base thickness.

In 1947, the United States Justice Department filed an antitrust suit against Technicolor for monopolization of color cinematography through their 1934 "Monopack Agreement" with Kodak (even though rival processes such as Cinecolor and Trucolor were in general use).

[21][22] In 1950, a federal court ordered Technicolor to allot a number of its three-strip cameras for use by independent studios and filmmakers.

[3] In the field of motion pictures, the many-layered type of color film normally called an integral tripack in broader contexts has long been known by the less tongue-twisting term monopack.

Essentially, the "Imbibition Agreement" lifted a portion of the "Monopack Agreement's" restrictions on Technicolor (which prevented it from making motion picture products less than 35mm wide) and somewhat related restrictions on Eastman Kodak (which prevented it from experimenting and developing monopack products greater than 16mm wide).

This is Cinerama was initially printed on Eastmancolor positive, but its significant success eventually resulted in it being reprinted by Technicolor, using dye-transfer.

This nearly fatal flaw was not corrected until 1955 and caused numerous features initially printed by Technicolor to be scrapped and reprinted by DeLuxe Labs.

[27] [28] This has recently gained significant attention online as a result of the Blu-Ray editions of Sailor Moon having a pink tint due to film fading and no color correction being applied.

Each color is separated by a gelatin layer that prevents silver development in one record from causing unwanted dye formation in another.

In the late 1980s, Kodak introduced the T-Grain emulsion, a technological advancement in the shape and make-up of silver halide grains in their films.

In 2005, Fuji unveiled their Eterna 500T stock, the first in a new line of advanced emulsions, with Super Nano-structure Σ Grain Technology.