Colorado War

The Kiowa and the Comanche played a minor role in actions that occurred in the southern part of the Territory along the Arkansas River.

The war included an attack in November 1864 against the winter camp of the Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle known as the Sand Creek massacre.

The massacre resulted in military and congressional hearings which established the culpability of John M. Chivington, the commander of the Colorado Volunteers, and his troops.

En route they carried out extensive raids along the South Platte River and attacked U.S. military forts and forces, successfully eluding defeat and capture by the U.S. army.

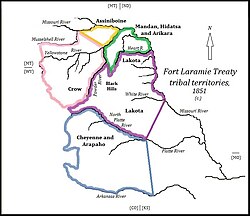

By the terms of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie between the United States and a few representatives of various tribes including the Cheyenne and Arapaho,[2] the United States unilaterally defined and recognized Cheyenne and Arapaho territory as ranging from the North Platte River in present-day Wyoming and Nebraska southward to the Arkansas River in present-day Colorado and Kansas.

The treaty did not – as is often falsely assumed – "allocate territory" to various tribes but endeavoured to make declaratory delineations of already existing sovereign tribal lands through which the US merely secured a right of way.

[3] Colorado territorial officials pressured federal authorities to redefine and reduce the extent of Indian treaty lands.

The whites, however, claimed the treaty was a "solemn obligation" and considered that those Indians who refused to abide by it were hostile and planning a war.

On April 9, however, Colonel John Chivington, commander of the Colorado volunteers, reported that Indians had stolen 175 head of cattle from whites.

[12] The mixed blood Cheyenne warrior, George Bent, said that the Indians were puzzled by what they regarded as unprovoked attacks by soldiers.

[17] Also, in May, Major Jacob Downing and a force of Colorado volunteers attacked a Cheyenne village in Cedar Canyon north of the South Platte River.

[18] On June 11, only 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Denver, four Arapaho killed the four members of the Hungate family, creating fear in the city that the war was on their doorstep.

On September 25, Major General James G. Blunt with 400 soldiers and Delaware Indian scouts encountered Cheyennes on the Pawnee Fork of the Arkansas River.

In response, Major Edward W. Wynkoop, the commander of Fort Lyon (near present-day Lamar, Colorado) led a force of 130 men to try to recover the prisoners.

In talks with Black Kettle and others, Wynkoop invited the chiefs to visit Denver to meet with the governor, John Evans, and Colonel Chivington.

The meetings at Camp Weld ended with Black Kettle and the other chiefs apparently believing that they had made peace with the whites.

The plains, from Julesburg west, for more than one hundred miles, are red with the blood of murdered men, women, and children – ranches are in ashes – stock all driven off – the country utterly desolate.

[27] Julesburg consisted of a stagecoach station, stables, an express and telegraph office, a warehouse, and a large store that catered to travelers going to Denver along the South Platte.

After the raid, Black Kettle and 80 lodges of his followers (perhaps 100 men and their families) left the main body and joined the Kiowa and Comanche south of the Arkansas River.

In the summer of 1865, the Indians launched a large-scale offensive in the Battle of Platte Bridge (present-day Casper, Wyoming) achieving a minor victory.

[35] Historian John D. McDermott said that the Colorado War was the last time the Northern and Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos and the Brulé Sioux were united to effectively resist the tide of white settlers and soldiers traveling through and settling on what had formerly been their lands.

[36][37] Black Kettle, always seeking peace, signed the Little Arkansas Treaty in October 1865 obligating his band of Southern Cheyenne to move to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

[40] Guerrier worked for a time as a scout for George Armstrong Custer in campaigns against his Cheyenne relatives and as an interpreter for many interactions between the tribe and the United States.

[41] In 1865, the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War investigated the Sand Creek massacre and concluded the following: "the truth is that he [Col. Chivington] surprised and murdered, in cold blood, the unsuspecting men, women, and children on Sand creek, who had every reason to believe they were under the protection of the United States authorities, and then returned to Denver and boasted of the brave deed he and the men under his command had performed.

Of the five conclusions outlined in their report, the first linked the ongoing conflicts with Indigenous Peoples directly to the actions of "lawless white men."

A group of legislators from the committee visited Fort Lyon in 1865 and told tribe members there that the government disapproved of Chivington's actions.