Ouray (Ute leader)

Ouray (/ˈjʊəreɪ/, c. 1833 – August 20, 1880) was a Native American chief of the Tabeguache (Uncompahgre) band of the Ute tribe, then located in western Colorado.

Raised in the culturally diverse town of Taos, Ouray learned to speak many languages that helped him in the negotiations, which were complicated by the manipulation of his grief over his five-year-old son, abducted during an attack by the Sioux.

Ouray met with Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and Hayes and was called the "man of peace" because he sought to make treaties with settlers and the government.

Ouray was known as the "White man's friend," and his services were almost indispensable to the government in negotiating with his tribe, who kept in good faith all treaties that were made by him.

[3] It might be added that Ouray himself, who pronounced his name as 'You-ray', never seemed to have objected to being called 'Chief of all the Utes' and he did not hesitate to sign documents by that title.

[1] Disturbed by the treaties that Ouray entered into, his brother-in-law "Hot Stuff" tried to kill him with an axe during his near-daily visit to the Los Piños Indian Agency in 1874.

[10] In 1862, he convinced Utes to negotiate with the government to enter into a treaty to ensure the protection of hereditary lands of the Tabeguache.

[6] Kit Carson had noticed in 1862 that prospectors were mining and settling in areas that had been traditional hunting grounds for the Utes and game was becoming scarce.

[8] Following an uprising by Chief Kaniatse, Colonel Kit Carson successfully negotiated a treaty with the Ouray and other Ute leaders in 1867.

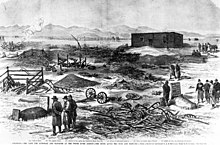

[8] In 1868, Ouray, Nicaagat, with Kit Carson were among a delegation to negotiate a treaty that would result in the creation of a reservation for the Ute,[11][8] served by an Indian Agencies at White River and near Montrose with a school, blacksmith shop, sawmill, and warehouse.

[8] Feeding on his grief due to the unknown status of his son after the Utes were attacked by the Sioux, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Felix Brunot had a 17-year-old orphan brought by Arapaho Chief Powder Face to meet Ouray and Chipeta in Washington, D.C. ten years after the abduction.

This was the first of many attempts by Brunot to find his son and was conducted so that Ouray would relinquish mining property and keep treaty talks open.

In 1873, with Ouray's help, the Brunot Agreement was ratified and the United States acquired the mineral-rich property they had been seeking.

The hostages, including Josephine Meeker, were delivered to Ouray's house at the Los Piños Indian Agency and were cared for by Chipeta.

[citation needed] When President Rutherford B. Hayes met Ouray in Washington, DC, he said that the Ute was "the most intellectual man I've ever conversed with.

"[2] When he had returned to Colorado, and while dying with Bright's disease, Ouray traveled to the Ignacio Indian Agency office to have the treaty signed by the Southern Utes.

[16] Ouray's first wife, Black Mare, died after the birth of their only child, a boy named Queashegut, also known as Pahlone, and called Paron (apple) by his father because of his round, dimpled face.

"[1][2] While visiting Kit Carson at Fort Garland in 1866, Ouray and Chipeta met and adopted two girls and two boys.

[1][d] Forty-five years later, in 1925, his bones were re-interred in a full ceremony led by Buckskin Charley and John McCook at the Ignacio cemetery.

[1][19] A 1928 article in the Denver Post reads in part, "He saw the shadow of doom on his people" and a 2012 article writes, "He sought peace among tribes and whites, and a fair shake for his people, though Ouray was dealt a sad task of liquidating a once-mighty force that ruled nearly 23 million acres of the Rocky Mountains.