Columbia, Maryland

In 1957, Rouse formed Community Research and Development, Inc. (CRD) for the purpose of building, owning and operating shopping centers throughout the country.

Rouse's ideas about what a new model city should be like were informed by a number of factors, including his personal Christian faith as well as the goal for his company to earn a profit, influences that he did not consider to be incompatible with one another.

[12] After exploring possible new city locations near Atlanta, Georgia, and Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, Rouse focused his attention between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in Howard County, Maryland.

[16]: 58 The $19,122,622 acquisition was then funded by Rouse's former employer Connecticut General Life Insurance in October 1962 at an average price of $1,500 per acre ($0.37/m2).

J. Hubert Black, Charles E. Miller, and David W. Force who campaigned on a low-density growth ballot, but later approved the Columbia project.

[16]: 64 In June 1965 zoning was approved for the project, and Howard Research and Development entered into a $37.5 million construction deed backed by the property.

[26] Miller had been defeated in the November 1974 Howard County Council elections, in part as a result of the changed political landscape that Columbia's development brought.

[27] At the unveiling on June 21, 1967, James Rouse described Columbia as a planned new city which would avoid the leap-frog and spot-zoning development threatening the county.

The urban planning process for Columbia included not only planners, but also a convened panel of nationally recognized experts in the social sciences, known as the Work Group.

The fourteen member group of men and one woman, Antonia Handler Chayes, met for two days, twice a month, for half a year starting in 1963.

[16]: 68 The Work Group suggested innovations for planners in education, recreation, religion, and health care, as well as ways of improving social interactions.

Columbia's "New Town District" zoning ordinance gave developers great flexibility about what to put where, without requiring county approval for each specific project.

"[28] In 1969, County Executive Omar J. Jones felt that the increase in tax base was lagging behind the need for infrastructure as the operating budget doubled to $15 million in three years.

[30][31] By 1970, the project required additional financing to continue, borrowing $30 million from Connecticut General, Manufacturers Hanover Trust, and Morgan Guaranty.

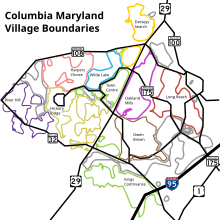

[citation needed] To achieve the goals set forth by the Work Group, Columbia's Master Plan called for a series of ten self-contained villages, around which day-to-day life would revolve.

Four of the villages have interfaith centers, common worship facilities which are owned and jointly operated by a variety of religious congregations working together.

[43] An outer ring of greenspace was abandoned early in the project because the combination with the already required river buffers would have reduced profitable land available for building.

James Rouse conceived of a city, not a suburban bedroom community, and a large area on the eastern edge was allocated for industrial purposes.

[16]: 141 One section of the property was subsequently redeveloped for big box retail; the remainder became the large Gateway Commerce office complex, still being expanded.

There are several other major competing shopping centers in East Columbia, including Dobbin Center strip mall opened in 1983, Snowden Square big box retail on the remainder of the GE industrial site, Columbia Crossing I and II big box retail started in 1997, and Gateway Overlook.

[16]: 142 Columbia's nine "village centers" provide residents with nearby shopping as well, often including supermarkets, filling stations, liquor stores, dry cleaners, restaurants, and hair salons.

Most historic buildings, mills and plantations within Columbia that qualified for the register, such as Oakland Manor,[64] were not submitted by Rouse company affiliates.

[12] Dr. Stanley Hallet advised this 1964 work group to economically abandon "The extravagance of church life" in favor of ecumenical establishments that focused resources on retreat centers and non-profit religious corporations.

[66][67] On June 22, 1969, $2.5 million in church donations applied to the CFRC to purchase Columbia land and build an interfaith facility in the village of Wilde Lake.

CA operates a variety of recreational facilities, including 23 outdoor swimming pools, five indoor pools, two water slides, ice and roller skating rinks, an equestrian center, a sports park with miniature golf, a skateboard park, batting cages, picnic pavilions, clubhouse and playground, three athletic clubs, numerous indoor and outdoor tennis, basketball, volleyball, squash, pickleball, and racquetball courts, and running tracks.

There are a variety of fairs and celebrations throughout the year, including entertainment on the lakefront of Lake Kittamaqundi during the summer and the Columbia Festival of the Arts.

Columbia's initial plan called for a minibus system connecting the village centers on a distinct right-of-way that allowed denser development along the route.

Six Howard Transit bus routes served Columbia and connected it with its neighboring areas (such as Ellicott City and the BWI Airport) until they were replaced by Regional Transportation Agency of Central Maryland (RTA) in 2014.

[90] The novel is largely set in Baltimore City and describes Columbia as a utopian experiment with huge homes and affluent residents.

[94] Columbia is a sister city to Cergy-Pontoise, France, Tres Cantos, Spain, Tema, Ghana, Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, and Liyang, China.