World's Columbian Exposition

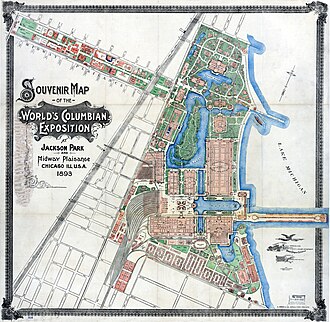

The layout of the Chicago Columbian Exposition was predominantly designed by John Wellborn Root, Daniel Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Charles B.

The exposition covered 690 acres (2.8 km2), featuring nearly 200 new but temporary buildings of predominantly neoclassical architecture, canals and lagoons, and people and cultures from 46 countries.

[5] Many prominent civic, professional, and commercial leaders from around the United States helped finance, coordinate, and manage the Fair, including Chicago shoe company owner Charles H. Schwab,[6] Chicago railroad and manufacturing magnate John Whitfield Bunn, and Connecticut banking, insurance, and iron products magnate Milo Barnum Richardson, among many others.

World's fairs, such as London's 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition, had been successful in Europe as a way to bring together societies fragmented along class lines.

In a Senate hearing held in January 1890, representative Thomas Barbour Bryan argued that the most important qualities for a world's fair were "abundant supplies of good air and pure water", "ample space, accommodations and transportation for all exhibits and visitors".

He argued that New York had too many obstructions, and Chicago would be able to use large amounts of land around the city where there was "not a house to buy and not a rock to blast" and that it would be located so that "the artisan and the farmer and the shopkeeper and the man of humble means" would be able to easily access the fair.

[9] The Exposition's offices set up shop in the upper floors of the Rand McNally Building on Adams Street, the world's first all-steel-framed skyscraper.

"[13] Ten thousand copies of the pamphlet were circulated in the White City from the Haitian Embassy (where Douglass had been selected as its national representative), and the activists received responses from the delegations of England, Germany, France, Russia, and India.

Black individuals were also featured in white exhibits, such as Nancy Green's portrayal of the character Aunt Jemima for the R. T. Davis Milling Company.

The layout of the fairgrounds was created by Frederick Law Olmsted, and the Beaux-Arts architecture of the buildings was under the direction of Daniel Burnham, Director of Works for the fair.

The lagoon was reshaped to give it a more natural appearance, except for the straight-line northern end where it still laps up against the steps on the south side of the Palace of Fine Arts/Museum of Science & Industry building.

[26] The celebration of Columbus was an intergovernmental project, coordinated by American special envoy William Eleroy Curtis, the Queen Regent of Spain, and Pope Leo XIII.

[28][29] Eadweard Muybridge gave a series of lectures on the Science of Animal Locomotion in the Zoopraxographical Hall, built specially for that purpose on Midway Plaisance.

Nearby, historian Frederick Jackson Turner gave academic lectures reflecting on the end of the frontier which Buffalo Bill represented.

Architect Kirtland Cutter's Idaho Building, a rustic log construction, was a popular favorite,[33] visited by an estimated 18 million people.

The newly built Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad also served passengers from Congress Terminal to the fairgrounds at Jackson Park.

The German firm Krupp had a pavilion of artillery, which apparently had cost one million dollars to stage,[42] including a coastal gun of 42 cm in bore (16.54 inches) and a length of 33 calibres (45.93 feet, 14 meters).

According to Eric J. Sharpe, Tomoko Masuzawa, and others, the event was considered radical at the time, since it allowed non-Christian faiths to speak on their own behalf.

Façades were made not of stone, but of a mixture of plaster, cement, and jute fiber called staff, which was painted white, giving the buildings their "gleam".

[55] As detailed in Erik Larson's popular history The Devil in the White City, extraordinary effort was required to accomplish the exposition, and much of it was unfinished on opening day.

The famous Ferris Wheel, which proved to be a major attendance draw and helped save the fair from bankruptcy, was not finished until June, because of waffling by the board of directors the previous year on whether to build it.

Buffalo Bill set up his highly popular show next door to the fair and brought in a great deal of revenue that he did not have to share with the developers.

The White City so impressed visitors (at least before air pollution began to darken the façades) that plans were considered to refinish the exteriors in marble or some other material.

Frank Lloyd Wright later wrote that "By this overwhelming rise of grandomania I was confirmed in my fear that a native architecture would be set back at least fifty years.

Swami Vivekananda visited the fair to attend the Parliament of the World's Religions and delivered his famous speech Sisters and Brothers of America!.

Part of the space occupied by the Westinghouse Company was devoted to demonstrations of electrical devices developed by Nikola Tesla[74] including induction motors and the generators used to power the system.

[76] Tesla himself showed up for a week in August to attend the International Electrical Congress, being held at the fair's Agriculture Hall, and put on a series of demonstrations of his wireless lighting system in a specially set up darkened room at the Westinghouse exhibit.

[81] There were many other black artists at the fair, ranging from minstrel and early ragtime groups to more formal classical ensembles to street buskers.

[111] A large Romanesque structure called "Greatest Refrigerator on Earth" stored thousands of pounds of the Exposition's food and held an ice-skating rink for patrons.

[128] Henry Adams wrote in his 1907 Education: “The Exposition denied philosophy ... [S]ince Noah’s Ark, no such Babel of loose and ill-jointed, such vague and ill-defined and unrelated thoughts and half-thoughts and experimental out-cries... had ruffled the surface of the Lakes.”[129]: 128 Michel-Rolph Trouillot wrote that the academic aspect of the event was not very important, even though the Harvard Peabody Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, and Franz Boas made contributions.