Columbian mammoth

Several sites contain the skeletons of multiple Columbian mammoths, either because they died in incidents such as a drought, or because these locations were natural traps in which individuals accumulated over time.

The extinction of the Columbian mammoth and other American megafauna was most likely a result of habitat loss caused by climate change, hunting by humans, or a combination of both.

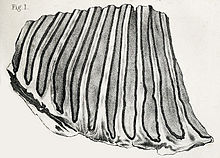

[1] The Columbian mammoth was first scientifically described in 1857 by the Scottish naturalist Hugh Falconer, who named the species Elephas columbi after the explorer Christopher Columbus.

The animal was brought to Falconer's attention in 1846 by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell, who sent him molar fragments found during the 1838 excavation of the Brunswick–Altamaha Canal in Georgia, in the southeastern United States.

Although scientists William Phipps Blake and Richard Owen believed that E. texianus was more appropriate for the species, Falconer rejected the name; he also suggested that E. imperator and E. jacksoni, two other American elephants described from molars, were based on remains too fragmentary to classify properly.

In 1942, the American paleontologist Henry F. Osborn's posthumous monograph on the Proboscidea was published, wherein he used various generic and subgeneric names that had previously been proposed for extinct elephant species, such as Archidiskodon, Metarchidiskodon, Parelephas, and Mammonteus.

Osborn also retained names for many regional and intermediate subspecies or "varieties", and created recombinations such as Parelephas columbi felicis and Archidiskodon imperator maibeni.

Among many now extinct clades, the mastodon (Mammut) is only a distant relative, and part of the distinct family Mammutidae, which diverged 25 million years before the mammoths evolved.

[11] The Columbian mammoth evolved from a population of M. trogontherii that had crossed the Bering Strait and entered North America about 1.5-1.3 million years ago; it retained a similar number of molar ridges.

[18] In 2016, a genetic study of North American mammoth specimens confirmed that the mitochondrial diversity of M. columbi was nested within that of M. primigenius and suggested that both species interbred extensively, were both descended from M. trogontherii, and concluded that morphological differences between fossils may, therefore, not be reliable for determining taxonomy.

[19] In 2021, DNA older than a million years was sequenced for the first time, from two steppe mammoth-like teeth of Early Pleistocene age found in eastern Siberia.

In a 2024 review, Adrian Lister and Love Dalén argued that M. columbi should be retained in a broad sense covering the entire time-period of mammoth occupation of North America.

About a quarter of the tusks' length was inside the sockets; they grew spirally in opposite directions from the base, curving until the tips pointed towards each other, and sometimes crossed.

[31][32] Although to what extent Columbian mammoths migrated is unclear, an isotope analysis of Blackwater Draw in New Mexico indicated that they spent part of the year in the Rocky Mountains, 200 km (120 mi) away.

[31][33] Mathematical modelling indicates that Columbian mammoths would have had to have been periodically on the move to avoid starvation, as prolonged stays in one area would rapidly exhaust the food resources necessary to sustain a population.

In 2016, the herd was suggested to have died by drought near a diminishing watering hole; scavenging traces on the bones contradict rapid burial, and the absence of calves and the large diversity of other animal species found gathered at the site support this scenario.

[24][35] Since the early 20th century, excavations at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles have yielded 100 t (220,000 lb) of fossils from 600 species of flora and fauna, including several Columbian mammoths.

[38] A site in an airport construction area in Mexico nicknamed "mammoth central" is believed to have been the boggy shores of an ancient lake bed where animals were trapped 10,0000 to 20,000 years ago.

[44] Evidence from Florida reveals that Columbian mammoths typically preferred C4 grasses, but that they would alter their dietary habits and consume greater proportions of non-traditional foods during periods of significant environmental change.

[24] The Columbian mammoth shared its habitat with other now-extinct Pleistocene mammals such as Glyptotherium, the sabertooth cat Smilodon, ground sloths, the camel Camelops, mastodons, horses, and bison.

Fossils of woolly and Columbian mammoths have been found in the same place in a few areas of North America where their ranges overlapped, including the Hot Springs Site.

[55] Towards the end of the Late Pleistocene, around or after 16,000 years ago, Paleoindians entered the Americas through the Beringia landbridge,[56] and evidence documents their interactions with Columbian mammoths.

A female mammoth at the Naco-Mammoth Kill Site in Arizona, found with eight Clovis points near its skull, shoulder blade, ribs, and other bones, is considered the most convincing evidence for hunting.

However, isotope studies have shown that the accumulations represent individual deaths at different seasons of the year, so are not herds killed in single incidents.

In response, other scientists found no reason to abandon the traditional idea that Clovis points were used to hunt big-game, one suggesting that such spears could have been thrown or thrust at areas of the torso that were not protected by ribs, with the wounds not killing the mammoths instantly, but the hunters could follow their prey until it had bled to death.

[68] Geological dating of the San Juan River depictions in 2013 have shown them to be less than 4000 years old, after mammoths and mastodons went extinct, and they may instead be an arrangement of unrelated elements.

According to the climate-change hypothesis, warmer weather led to the shrinking of suitable habitat for Columbian mammoths, which turned from parkland to forest, grassland, and semidesert, with less diverse vegetation.

The "overkill hypothesis" attributes the extinction to hunting by humans, an idea first proposed by geoscientist Paul S. Martin in 1967; more recent research on this subject has varied in conclusions.

[79] In contrast, a 2007 study found that the Clovis record indicated the highest frequency of prehistoric exploitation of proboscideans for subsistence in the world, and supported the "overkill hypothesis".

[60] On the other hand, large mammals are generally less vulnerable to climatic stresses since they have greater fat deposits at their disposal[82] and can migrate long distances to escape food shortages.