Orthogenesis

Prominent historical figures who have championed some form of evolutionary progress include Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Henri Bergson.

The evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr made the term effectively taboo in the journal Nature in 1948, by stating that it implied "some supernatural force".

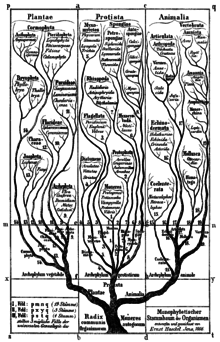

[9][10] Theodor Eimer was the first to give the word a definition; he defined orthogenesis as "the general law according to which evolutionary development takes place in a noticeable direction, above all in specialized groups".

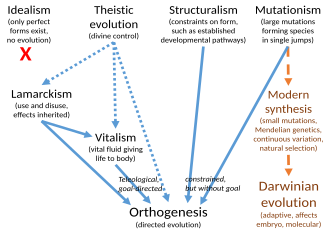

It ranged from theories of mystical forces to mere descriptions of a general trend in development due to natural limitations of either the germinal material or the environment ... By 1910, however most who subscribed to orthogenesis hypothesized some physical rather than metaphysical determinant of orderly change.

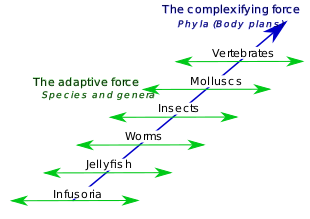

The concept, indeed, had its roots in Aristotle's biology, from insects that produced only a grub, to fish that laid eggs, and on up to animals with blood and live birth.

The medieval chain, as in Ramon Lull's Ladder of Ascent and Descent of the Mind, 1305, added steps or levels above humans, with orders of angels reaching up to God at the top.

The French zoologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) himself accepted the idea, and it had a central role in his theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics, the hypothesized mechanism of which resembled the "mysterious inner force" of orthogenesis.

[18] His grandfather, the physician and polymath Erasmus Darwin, was both progressionist and vitalist, seeing "the whole cosmos [as] a living thing propelled by an internal vital force" towards "greater perfection".

[19] Robert Chambers, in his popular anonymously published 1844 book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation presented a sweeping narrative account of cosmic transmutation, culminating in the evolution of humanity.

"[21][23][24] In 1864, the Swiss anatomist Albert von Kölliker (1817–1905) presented his orthogenetic theory, heterogenesis, arguing for wholly separate lines of descent with no common ancestor.

[2] Charles Darwin saw this as a serious challenge, replying that "There must be some efficient cause for each slight individual difference", but was unable to provide a specific answer without knowledge of genetics.

[27][28] Darwin indeed wrote in his 1859 Origin of Species:[29] The inhabitants of each successive period in the world's history have beaten their predecessors in the race for life, and are, insofar, higher in the scale of nature; and this may account for that vague yet ill-defined sentiment, felt by many palaeontologists, that organisation on the whole has progressed.

[35] For example, biologists such as Maynard M. Metcalf (1914), John Merle Coulter (1915), David Starr Jordan (1920) and Charles B. Lipman (1922) claimed evidence for orthogenesis in bacteria, fish populations and plants.

He believed this was purely mechanistic, denying any kind of vitalism, but that evolution occurs due to a periodic cycle of evolutionary processes dictated by factors internal to the organism.

[71] The stronger versions of the orthogenetic hypothesis began to lose popularity when it became clear that they were inconsistent with the patterns found by paleontologists in the fossil record, which were non-rectilinear (richly branching) with many complications.

[72] The historian of biology Edward J. Larson commented that At theoretical and philosophical levels, Lamarckism and orthogenesis seemed to solve too many problems to be dismissed out of hand—yet biologists could never reliably document them happening in nature or in the laboratory.

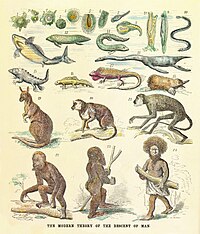

The philosopher of biology Michael Ruse wrote that "some of the most significant of today's evolutionists are progressionists, and that because of this we find (absolute) progressionism alive and well in their work.

[79] Presentations of evolution remain characteristically progressionist, with humans at the top of the "Tower of Time" in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., while Scientific American magazine could illustrate the history of life leading progressively from mammals to dinosaurs to primates and finally man.

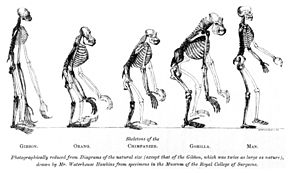

The historian Jennifer Tucker, writing in The Boston Globe, notes that Thomas Henry Huxley's 1863 illustration comparing the skeletons of apes and humans "has become an iconic and instantly recognizable visual shorthand for evolution.

The Origin of Species had only one illustration, a diagram showing that random events create a process of branching evolution, a view that Tucker notes is broadly acceptable to modern biologists.

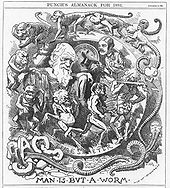

Edward Linley Sambourne's Man is But a Worm, drawn for Punch's Almanack, mocked the idea of any evolutionary link between humans and animals, with a sequence from chaos to earthworm to apes, primitive men, a Victorian beau, and Darwin in a pose that according to Tucker recalls Michelangelo's figure of Adam in his fresco adorning the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

"There it remained frozen, for nearly another hundred years",[4] until mathematicians such as Fisher[87] provided "both models and status", enabling evolutionary biologists to construct the modern synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s.

These butterflies are Müllerian mimics of each other, so natural selection is the driving force, but their wing patterns, which arose in separate evolutionary events, are controlled by the same genes.