Capital (architecture)

From the highly visible position it occupies in all colonnaded monumental buildings, the capital is often selected for ornamentation; and is often the clearest indicator of the architectural order.

The capital extends below for further than in most other styles, with decoration drawn from the many cultures that the Persian Empire conquered including Egypt, Babylon, and Lydia.

The earliest Aegean capital is that shown in the frescoes at Knossos in Crete (1600 BC); it was of the convex type, probably moulded in stucco.

Volute capitals, also known as proto-Aeolic capitals, are encountered in Iron-Age Southern Levant and ancient Cyprus, many of them in royal architectural contexts in the kingdoms of Israel and Judah starting from the 9th century BCE, as well as in Moab, Ammon, and at Cypriot sites such as the city-state of Tamassos in the Archaic period.

[2][3] The orders, structural systems for organising component parts, played a crucial role in the Greeks' search for perfection of ratio and proportion.

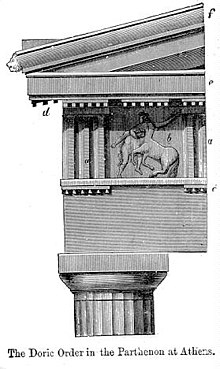

The Doric capital is the simplest of the five Classical orders: it consists of the abacus above an ovolo molding, with an astragal collar set below.

In the Temple of Apollo, Syracuse (c. 700 BC), the echinus moulding has become a more definite form: this in the Parthenon reaches its culmination, where the convexity is at the top and bottom with a delicate uniting curve.

The sloping side of the echinus becomes flatter in the later examples, and in the Colosseum at Rome forms a quarter round (see Doric order).

The Doric capital consists of a cushion-like convex moulding known as an echinus, and a square slab termed an abacus.

This order appears to have been developed contemporaneously with the Doric, though it did not come into common usage and take its final shape until the mid-5th century BC.

According to the Roman architect Vitruvius, the Ionic order's main characteristics were beauty, femininity, and slenderness, derived from its basis on the proportion of a woman.

In Roman architectural practice, capitals are briefly treated in their proper context among the detailing proper to each of the "Orders", in the only complete architectural textbook to have survived from classical times, the De architectura, by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, better known as Vitruvius, dedicated to the emperor Augustus.

Despite this origin, very many Composite capitals in fact treat the two volutes as different elements, each springing from one side of their leafy base.

In this, and in having a separate ornament between them, they resemble the Archaic Greek Aeolic order, though this seems not to have been the route of their development in early Imperial Rome.

[9] This powerfully carved lion capital from Sarnath stood a top a pillar bearing the edicts of the emperor Ashoka.

[10] Some capitals with strong Greek and Persian influence have been found in northeastern India in the Maurya Empire palace of Pataliputra, dating to the 4th–3rd century BC.

The Classical design was often adapted, usually taking a more elongated form, and sometimes being combined with scrolls, generally within the context of Buddhist stupas and temples.

Byzantine capitals vary widely, mostly developing from the classical Corinthian, but tending to have an even surface level, with the ornamentation undercut with drills.

One of the most remarkable designs features leaves carved as if blown by the wind; the finest example being at the 8th-century Hagia Sophia (Thessaloniki).

The composite capital that emerged during the Late Byzantine Empire, mainly in Rome, combines the Corinthian with the Ionic.

The capitals at Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (Italy) show wavy and delicate floral patterns similar to decorations found on belt buckles and dagger blades.

Capitals in early Islamic architecture are derived from Graeco-Roman and Byzantine forms, reflecting the training of most of the masons producing them.

In both periods, though there are common types, the sense of a strict order with rules was not maintained, and when the budget allowed, carvers were able to indulge their inventiveness.

The earliest type of capital in Lombardy and Germany is known as the cushion-cap, in which the lower portion of the cube block has been cut away to meet the circular shaft.

These capitals, however, are not equal to those of the Early English Gothic, in which foliage is treated as if copied from metalwork, and is of infinite variety, being found in small village churches as well as in cathedrals.

The flat pilaster, which was employed extensively in this period, called for a planar rendition of the capital, executed in high relief.

This had created an awkward transition at the corner – where, for example, the designer of the temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis in Athens had brought the outside volute of the end capitals forward at a 45-degree angle.

This problem was more satisfactorily solved by the 16th-century architect Sebastiano Serlio, who angled outwards all volutes of his Ionic capitals.

Since then use of antique Ionic capitals, instead of Serlio's version, has lent an archaic air to the entire context, as in Greek Revival.

When Benjamin Latrobe redesigned the Senate Vestibule in the United States Capitol in 1807, he introduced six columns that he "Americanized" with ears of corn (maize) substituting for the European acanthus leaves.