Combinatorial chemistry

Combinatorial chemistry comprises chemical synthetic methods that make it possible to prepare a large number (tens to thousands or even millions) of compounds in a single process.

The basic principle of combinatorial chemistry is to prepare libraries of a very large number of compounds and identify those which are useful as potential drugs or agrochemicals.

[2] Although combinatorial chemistry has only really been taken up by industry since the 1990s,[3] its roots can be seen as far back as the 1960s when a researcher at Rockefeller University, Bruce Merrifield, started investigating the solid-phase synthesis of peptides.

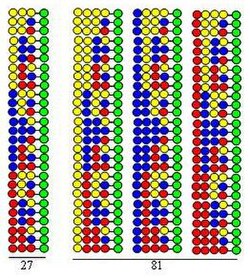

Solid-phase methods for small molecules were later introduced and Furka devised a "split and mix" approach[2][4] In its modern form, combinatorial chemistry has probably had its biggest impact in the pharmaceutical industry.

[6][7] Advances in robotics have led to an industrial approach to combinatorial synthesis, enabling companies to routinely produce over 100,000 new and unique compounds per year.

The researcher will select a subset of the 'virtual library' for actual synthesis, based upon various calculations and criteria (see ADME, computational chemistry, and QSAR).

As the founding editor of the American Chemical Society's Journal of Combinatorial Chemistry, he also led research into RFID tags for targeted sorting in compound library synthesis.

[14] If a combinatorial peptide library is synthesized using 20 amino acids (or other kinds of building blocks) the bead form solid support is divided into 20 equal portions.

Combinatorial chemistry has emerged in recent decades as an approach to quickly and efficiently synthesize large numbers of potential small molecule drug candidates.

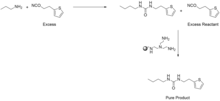

In a combinatorial synthesis, when using only single starting material, it is possible to synthesize a large library of molecules using identical reaction conditions that can then be screened for their biological activity.

Solid-phase synthesis offers potential solutions to obviate the need for typical quenching and purification steps often used in synthetic chemistry.

Armstrong, et al. describe a one-pot method for generating combinatorial libraries, called multiple-component condensations (MCCs).

The beauty of this method is that the identity of each product can be known simply by its location along the thread, and the corresponding biological activity is identified by Fourier transformation of fluorescence signals.

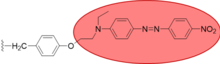

Ellman uses solid phase supports in a multi-step synthesis scheme to obtain 192 individual 1,4-benzodiazepine derivatives, which are well-known therapeutic agents.

[31] Gordon et al., describe several case studies that utilize imines and peptidyl phosphonates to generate combinatorial libraries of small molecules.

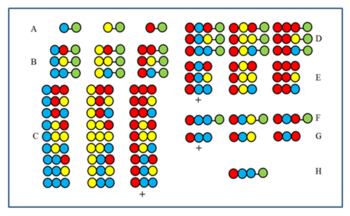

Combinatorial libraries are special multi-component mixtures of small-molecule chemical compounds that are synthesized in a single stepwise process.

For practical reasons however, it is advisable to use the split-mix method in which one of two mixtures is replaced by single building blocks (BBs).

Some of them can be used in deconvolution[32] If the synthesized molecules of a combinatorial library are cleaved from the solid support a soluble mixture forms.

The method is based on the heat that is evolved in the beads that contain a catalyst when the tethered library immersed into a solution of a substrate.

Ohlmeyer and his colleagues published a binary encoding method[40] They used mixtures of 18 tagging molecules that after cleaving them from the beads could be identified by Electron Capture Gas Chromatography.

Sarkar et al. described chiral oligomers of pentenoic amides (COPAs) that can be used to construct mass encoded OBOC libraries.

[41] Kerr et al. introduced an innovative encoding method[42] An orthogonally protected removable bifunctional linker was attached to the beads.

The next generation techniques make it possible to sequence large number of samples in parallel that is very important in screening of DNA encoded libraries.

By the novel approach of the authors, this restraint was eliminated and made it possible to prepare new compounds in practically unlimited number.

components[47] The DNA encoded libraries are soluble that makes possible to apply the efficient affinity binding in screening.

In addition, the polyionic character of DNA encoding chains limits the utility of non-aqueous solvents in the synthesis.

Schultz et al. in the mid-nineties [56] in the context of luminescent materials obtained by co-deposition of elements on a silicon substrate.

Work has been continued by several academic groups[58][59][60][61] as well as companies with large research and development programs (Symyx Technologies, GE, Dow Chemical etc.).

[68] The analysis of the poor success rate of the approach has been suggested to connect with the rather limited chemical space covered by products of combinatorial chemistry.

[69] When comparing the properties of compounds in combinatorial chemistry libraries to those of approved drugs and natural products, Feher and Schmidt[69] noted that combinatorial chemistry libraries suffer particularly from the lack of chirality, as well as structure rigidity, both of which are widely regarded as drug-like properties.