Comics

Comics has had a lowbrow reputation for much of their history, but towards the end of the 20th century, they began to find greater acceptance with the public and academics.

The ukiyo-e artist Hokusai popularized the Japanese term for comics and cartooning, manga, in the early 19th century.

[14] In the post-war era modern Japanese comics began to flourish when Osamu Tezuka produced a prolific body of work.

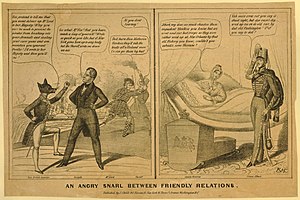

[7] Outside of these genealogies, comics theorists and historians have seen precedents for comics in the Lascaux cave paintings[16] in France (some of which appear to be chronological sequences of images), Egyptian hieroglyphs, Trajan's Column in Rome,[17] the 11th-century Norman Bayeux Tapestry,[18] the 1370 bois Protat woodcut, the 15th-century Ars moriendi and block books, Michelangelo's The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel,[17] and William Hogarth's 18th-century sequential engravings,[19] amongst others.

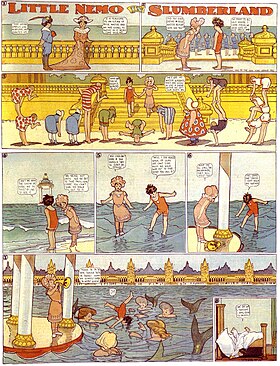

[26] An example is Gustave Verbeek, who wrote his comic series "The UpsideDowns of Old Man Muffaroo and Little Lady Lovekins" between 1903 and 1905.

In 2012, a remake of a selection of the comics was made by Marcus Ivarsson in the book 'In Uppåner med Lilla Lisen & Gamle Muppen'.

(ISBN 978-91-7089-524-1) Shorter, black-and-white daily strips began to appear early in the 20th century, and became established in newspapers after the success in 1907 of Bud Fisher's Mutt and Jeff.

[27] In Britain, the Amalgamated Press established a popular style of a sequence of images with text beneath them, including Illustrated Chips and Comic Cuts.

[30] In the UK and the Commonwealth, the DC Thomson-created Dandy (1937) and Beano (1938) became successful humor-based titles, with a combined circulation of over 2 million copies by the 1950s.

Their characters, including "Dennis the Menace", "Desperate Dan" and "The Bash Street Kids" have been read by generations of British children.

[38] The underground gave birth to the alternative comics movement in the 1980s and its mature, often experimental content in non-superhero genres.

[45] The francophone Swiss Rodolphe Töpffer produced comic strips beginning in 1827,[17] and published theories behind the form.

[60] A group including René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo founded the magazine Pilote in 1959 to give artists greater freedom over their work.

[63] Frustration with censorship and editorial interference led to a group of Pilote cartoonists to found the adults-only L'Écho des savanes in 1972.

[69] Japanese comics and cartooning (manga),[g] have a history that has been seen as far back as the anthropomorphic characters in the 12th-to-13th-century Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, 17th-century toba-e and kibyōshi picture books,[73] and woodblock prints such as ukiyo-e which were popular between the 17th and 20th centuries.

[75] Illustrated magazines for Western expatriates introduced Western-style satirical cartoons to Japan in the late 19th century.

[77] By the 1930s, comic strips were serialized in large-circulation monthly girls' and boys' magazine and collected into hardback volumes.

Modern manhwa has gained global popularity, partly due to the rise of webtoons—digitally formatted comics designed for scrolling on mobile devices.

Manga’s established presence in Japan during this period strongly shaped the foundational styles and formats of Korean comics.

As Korea transitioned into independence, manhwa evolved into a distinct medium, balancing the artistic influences of its neighbors with traditional Korean aesthetics and storytelling.

European comic albums are most commonly colour volumes printed at A4-size, a larger page size than used in many other cultures.

[94] Webcomics can make use of an infinite canvas, meaning they are not constrained by the size or dimensions of a printed comics page.

[101] Theorists such as Töpffer,[102] R. C. Harvey, Will Eisner,[103] David Carrier,[104] Alain Rey,[100] and Lawrence Grove emphasize the combination of text and images,[105] though there are prominent examples of pantomime comics throughout its history.

[107] European comics studies began with Töpffer's theories of his own work in the 1840s, which emphasized panel transitions and the visual–verbal combination.

[109] In 1987, Henri Vanlier introduced the term multicadre, or "multiframe", to refer to the comics page as a semantic unit.

[110] By the 1990s, theorists such as Benoît Peeters and Thierry Groensteen turned attention to artists' poïetic creative choices.

[109] Thierry Smolderen and Harry Morgan have held relativistic views of the definition of comics, a medium that has taken various, equally valid forms over its history.

[110] In the mid-2000s, Neil Cohn began analyzing how comics are understood using tools from cognitive science, extending beyond theory by using actual psychological and neuroscience experiments.

Eisner described what he called "sequential art" as "the arrangement of pictures or images and words to narrate a story or dramatize an idea";[120] Scott McCloud defined comics as "juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer",[121] a strictly formal definition which detached comics from its historical and cultural trappings.

[110] Aaron Meskin saw McCloud's theories as an artificial attempt to legitimize the place of comics in art history.