Johannine Comma

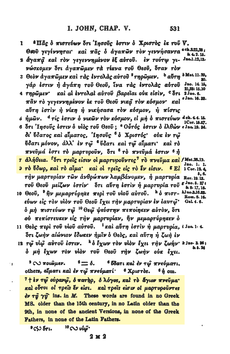

In the Greek Textus Receptus (TR), the verse reads thus:[2]ὅτι τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες εν τῷ οὐρανῷ, ὁ πατήρ, ὁ λόγος, καὶ τὸ Ἅγιον Πνεῦμα· καὶ οὗτοι οἱ τρεῖς ἕν εἰσι.It became a touchpoint for the Christian theological debate over the doctrine of the Trinity from the early church councils to the Catholic and Protestant disputes in the early modern period.

The Comma Johanneum is among the most noteworthy variants found within the Textus Receptus in addition to the confession of the Ethiopian eunuch, the long ending of Mark, the Pericope Adulterae, the reading "God" in 1 Timothy 3:16 and the "Book of Life" in Revelation 22:19.

[18] The first undisputed work to quote the Comma Johanneum as an actual part of the Epistle's text appears to be the 4th-century Latin homily Liber Apologeticus, probably written by Priscillian of Ávila (died 385), or his close follower Bishop Instantius.

[60] The Treatise on Rebaptism, placed as a 3rd-century writing and transmitted with Cyprian's works, has two sections that directly refer to the earthly witnesses, and thus has been used against authenticity by Nathaniel Lardner, Alfred Plummer and others.

However, because of the context being water baptism and the precise wording being "et isti tres unum sunt", the Matthew Henry Commentary uses this as evidence for Cyprian speaking of the heavenly witnesses in Unity of the Church.

Indeed, it has come to our notice that in this letter some unfaithful translators have gone far astray from the truth of the faith, for in their edition they provide just the words for three [witnesses]—namely water, blood and spirit—and omit the testimony of the Father, the Word and the Spirit, by which the Catholic faith is especially strengthened, and proof is tendered of the single substance of divinity possessed by Father, Son and Holy Spirit.77[63]The Prologue presents itself as a letter of Jerome to Eustochium, to whom Jerome dedicated his commentary on the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel.

That is, the Spirit of sanctification, and the blood of redemption, and the water of baptism; which three things are one, and remain undivided ...[84]This epistle from Leo was considered by Richard Porson to be the "strongest proof" of verse inauthenticity.

[91] The Cyprian citation, dating to more than a century before any extant Epistle of John manuscripts and before the Arian controversies that are often considered pivotal in verse addition/omission debate, remains a central focus of comma research and textual apologetics.

The contrasting position is that there are in fact such references, and that "evidences from silence" arguments, looking at the extant early church writer material, should not be given much weight as reflecting absence in the manuscripts—with the exception of verse-by-verse homilies, which were uncommon in the Ante-Nicene era.

In the scholium on Psalm 123 attributed to Origen is the commentary: spirit and body are servants to masters, Father and Son, and the soul is handmaid to a mistress, the Holy Ghost; and the Lord our God is the three (persons), for the three are one.

[103] Ellsworth especially noted the Richard Porson comment in response to the evidence of the Psalm commentary: "The critical chemistry which could extract the doctrine of the Trinity from this place must have been exquisitely refining".

[118] "The Comma ... was invoked at Carthage in 484 when the Catholic bishops of North Africa confessed their faith before Huneric the Vandal (Victor de Vita, Historia persecutionis Africanae Prov 2.82 [3.11]; CSEL, 7, 60).

"[119] The Confession of Faith representing the hundreds of Orthodox bishops[120] included the following section, emphasizing the heavenly witnesses to teach luce clarius ("clearer than the light"): And so, no occasion for uncertainty is left.

Ebrard, in referencing this quote, comments, "We see that he had before him the passage in his New Testament in its corrupt form (aqua, sanguis et caro, et tres in nobis sunt); but also, that the gloss was already in the text, and not merely in a single copy, but that it was so widely diffused and acknowledged in the West as to be appealed to by him bona fide in his contest with his Arian opponents.

From Responsio contra Arianos ("Reply against the Arians"; Migne (Ad 10; CC 91A, 797)): In the Father, therefore, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, we acknowledge unity of substance, but dare not confound the persons.

In Complexiones in Epistolis Apostolorum, first published in 1721 by Scipio Maffei, in the commentary section on 1 John, from the Cassiodorus corpus, is written: On earth three mysteries bear witness, the water, the blood, and the spirit, which were fulfilled, we read, in the passion of the Lord.

"[137] In the early 7th century, the Testimonia Divinae Scripturae et Patrum is often attributed to Isidore of Seville: De Distinctions personarum, Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti.In Epistola Joannis.

When the Fourth Council of the Lateran was held in 1215 at Rome, with hundreds of Bishops attending, the understanding of the heavenly witnesses was a primary point in siding with Lombard, against the writing of Joachim.

There are three that bear Record in Heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost and these three are one ..."[28] The Epistle of Gregory, the Bishop of Sis, to Haitho c. 1270 utilized 1 John 5:7 in the context of the use of water in the mass.

Vulgate scholar Samuel Berger reports on Corbie MS 13174 in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris that shows the scribe listing four distinct textual variations of the heavenly witnesses.

Erasmian scholar John Jack Bateman, discussing the Paraphrase and the Ratio uerae theologiae, says of these uses of the comma that "Erasmus attributes some authority to it despite any doubts he had about its transmission in the Greek text.

"[151] The New Testament of Erasmus provoked critical responses that focused on a number of verses, including his text and translation decisions on Romans 9:5, John 1:1, 1 Timothy 1:17, Titus 2:13 and Philippians 2:6.

[12] This change was accepted into editions based on the Textus Receptus, the chief source for the King James Version, thereby fixing the comma firmly in the English-language scriptures for centuries.

And about the 16th-century controversies, Thomas Burgess summarized "In the sixteenth century its chief opponents were Socinus, Blandrata, and the Fratres Poloni; its defenders, Ley, Beza, Bellarmine, and Sixtus Senensis.

There were writings by numerous additional scholars, including posthumous publication in London of Isaac Newton's Two Letters in 1754 (An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture), which he had written to John Locke in 1690.

Some highlights from this era are the Nicholas Wiseman Old Latin and Speculum scholarship, the defence of the verse by the Germans Immanuel Sander, Besser, Georg Karl Mayer and Wilhelm Kölling, the Charles Forster New Plea book which revisited Richard Porson's arguments, and the earlier work by his friend Arthur-Marie Le Hir,[165] Discoveries included the Priscillian reference and Exposito Fidei.

[166] Daniel McCarthy noted the change in position among the textual scholars,[167] and in French there was the sharp Roman Catholic debate in the 1880s involving Pierre Rambouillet, Auguste-François Maunoury, Jean Michel Alfred Vacant, Elie Philippe and Paulin Martin.

There were specialty papers by Anton Baumstark (Syriac reference), Norbert Fickermann (Augustine), Claude Jenkins (Bede), Mateo del Alamo, Teófilo Ayuso Marazuela, Franz Posset (Luther) and Rykle Borger (Peshitta).

He remarked that although it is possible in Greek to agree masculine or feminine nouns with neuter adjectives or pronouns, the reverse was unusual; one would more normally expect τρία εἰσι τὰ μαρτυροῦντα .

[187] However, according Daniel Wallace the grammar can be explained without a need for the Johannine comma, stating each article-participle phrase (οἱ μαρτυροῦντες) in 1 John 5:7-8 functions as a substantive and agrees with the natural gender (masculine) of the idea being expressed (persons).