Commutative ring

In contrast to fields, where every nonzero element is multiplicatively invertible, the concept of divisibility for rings is richer.

consists of symbols subject to certain rules that mimic the cancellation familiar from rational numbers.

For example, all ideals in a commutative ring are automatically two-sided, which simplifies the situation considerably.

For various applications, understanding the ideals of a ring is of particular importance, but often one proceeds by studying modules in general.

A ring is called Noetherian (in honor of Emmy Noether, who developed this concept) if every ascending chain of ideals

A ring is called Artinian (after Emil Artin), if every descending chain of ideals

A cornerstone of algebraic number theory is, however, the fact that in any Dedekind ring (which includes

as a function that takes the value f mod p (i.e., the image of f in the residue field R/p), this subset is the locus where f is non-zero.

The spectrum also makes precise the intuition that localisation and factor rings are complementary: the natural maps R → Rf and R → R / fR correspond, after endowing the spectra of the rings in question with their Zariski topology, to complementary open and closed immersions respectively.

Even for basic rings, such as illustrated for R = Z at the right, the Zariski topology is quite different from the one on the set of real numbers.

The spectrum contains the set of maximal ideals, which is occasionally denoted mSpec (R).

For an algebraically closed field k, mSpec (k[T1, ..., Tn] / (f1, ..., fm)) is in bijection with the set Thus, maximal ideals reflect the geometric properties of solution sets of polynomials, which is an initial motivation for the study of commutative rings.

(an entity that collects functions defined locally, i.e. on varying open subsets).

In such a situation S is also called an R-algebra, by understanding that s in S may be multiplied by some r of R, by setting The kernel and image of f are defined by ker(f) = {r ∈ R, f(r) = 0} and im(f) = f(R) = {f(r), r ∈ R}.

The kernel is an ideal of R, and the image is a subring of S. A ring homomorphism is called an isomorphism if it is bijective.

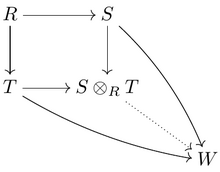

In some cases, the tensor product can serve to find a T-algebra which relates to Z as S relates to R. For example, An R-algebra S is called finitely generated (as an algebra) if there are finitely many elements s1, ..., sn such that any element of s is expressible as a polynomial in the si.

The residue field of R is defined as Any R-module M yields a k-vector space given by M / mM.

Nakayama's lemma shows this passage is preserving important information: a finitely generated module M is zero if and only if M / mM is zero.

For any Noetherian local ring R, the inequality holds true, reflecting the idea that the cotangent (or equivalently the tangent) space has at least the dimension of the space Spec R. If equality holds true in this estimate, R is called a regular local ring.

As of 2017, it is in general unknown, whether curves in three-dimensional space are set-theoretic complete intersections.

The aim of such constructions is often to improve certain properties of the ring so as to make it more readily understandable.

For example, if k is a field, k[[X]], the formal power series ring in one variable over k, is the I-adic completion of k[X] where I is the principal ideal generated by X.

Complete local rings satisfy Hensel's lemma, which roughly speaking allows extending solutions (of various problems) over the residue field k to R. Several deeper aspects of commutative rings have been studied using methods from homological algebra.

[5] The Quillen–Suslin theorem asserts that any finitely generated projective module over k[T1, ..., Tn] (k a field) is free, but in general these two concepts differ.

A local Noetherian ring is regular if and only if its global dimension is finite, say n, which means that any finitely generated R-module has a resolution by projective modules of length at most n. The proof of this and other related statements relies on the usage of homological methods, such as the Ext functor.

The importance of this standard construction in homological algebra stems can be seen from the fact that a local Noetherian ring R with residue field k is regular if and only if vanishes for all large enough n. Moreover, the dimensions of these Ext-groups, known as Betti numbers, grow polynomially in n if and only if R is a local complete intersection ring.

[6] A key argument in such considerations is the Koszul complex, which provides an explicit free resolution of the residue field k of a local ring R in terms of a regular sequence.

Despite being defined in terms of homological algebra, flatness has profound geometric implications.

[8] A graded ring R = ⨁i∊Z Ri is called graded-commutative if, for all homogeneous elements a and b, If the Ri are connected by differentials ∂ such that an abstract form of the product rule holds, i.e., R is called a commutative differential graded algebra (cdga).

An example is the complex of differential forms on a manifold, with the multiplication given by the exterior product, is a cdga.