Comparative mythology

[2] Anthropologist C. Scott Littleton defined comparative mythology as "the systematic comparison of myths and mythic themes drawn from a wide variety of cultures".

[1] To an extent, all theories about mythology follow a comparative approach—as scholar of religion Robert Segal notes, "by definition, all theorists seek similarities among myths".

This suggests that the Greeks, Romans, and Indians originated from a common ancestral culture, and that the names Zeus, Jupiter, Dyaus and the Germanic Tiu (cf.

The folklorist Vladimir Propp proposed that many Russian fairy tales have a common plot structure, in which certain events happen in a predictable order.

Creation myths address questions deeply meaningful to the society that shares them, revealing their central worldview and the framework for the self-identity of the culture and individual in a universal context.

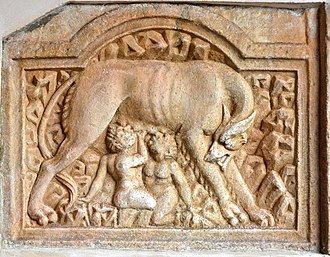

In Chinese mythology (see Chu Ci and Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era), Nüwa molded figures from the yellow earth, giving them life and the ability to bear children.

A protoplast, from ancient Greek πρωτόπλαστος (prōtóplastos, "first-formed"), in a religious context initially referred to the first human or, more generally, to the first organized body of progenitors of mankind in a creation myth.

A few examples include: in Greek mythology, according to Hesiod, the Titan Prometheus steals the heavenly fire for humanity, enabling the progress of civilization.

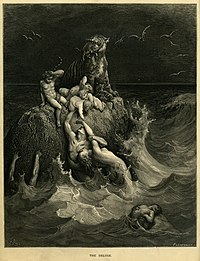

For example, both the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh and the Hebrew Bible tell of a global flood that wiped out humanity and of a man who saved the Earth's species by taking them aboard a boat.

[17] The flood narratives, spanning across different traditions such as Mesopotamian, Hebrew, Islamic, and Hindu, reveal striking similarities in their core elements, including divine warnings, ark construction, and the preservation of righteousness, highlighting the universal themes that thread through diverse religious beliefs.

[35] In the mythologies of highly complex cultures, the supreme being tends to disappear completely, replaced by a strong polytheistic belief system.

[36] In Greek mythology, "Chaos", the creator of the universe, disappears after creating primordial deities such as Gaea (Earth), Uranus (Sky), Pontus (Water) and Tartarus (Hell), among others.

[37] In the Greek myth of the Titanomachy, the Olympian gods defeat the Titans, an older and more primitive divine race, and establish cosmic order.

[37][38] In Norse mythology, the Aesir and Vanir are two distinct groups of gods who initially waged a war against each other, but eventually reconciled and formed a united pantheon In various mythologies, a group of "anti-gods" or adversarial beings oppose the main pantheon of gods, They embody chaos, destruction, or primal forces and are often considered demons or evil gods/divinities due to their opposition to divine order, symbolizing a struggle between cosmic order and chaos, good and evil.

[39][40] In particular, The Gigantomachy is a motif found in Greek mythology where the Olympian gods battle the Giants, often depicted as a cataclysmic struggle between order and chaos.

These are frequently portrayed as enemies of the gods, be they Greek (Giants), Celtic (Fomorians), Hindu (Asuras), Norse (Jötnar) or Persian (Daevas).

[41][42] The Mesopotamian myth of The Enuma Elish describes the conflict between the gods led by Marduk and the chaotic sea goddess Tiamat, who is often represented with monstrous forms.

In Egyptian mythology, Ra's nightly journey through the underworld involves a fierce struggle against Apep, the serpent of chaos, whose attempts to devour the sun god represent the ongoing battle between order and disorder.

In Abrahamic traditions, the War in Heaven refers to the celestial conflict described in Christian and Islamic texts, where the archangel Michael leads the faithful angels in a rebellion against Satan and his followers, who sought to overthrow God's divine authority.

This epic battle, depicted in Revelation 12:7-9 and alluded to in Islamic tradition, results in the expulsion of Satan and his demons from Heaven, reinforcing the ultimate triumph of divine order over chaos and evil.

In Norse mythology, the Ouroboros appears as the serpent Jörmungandr, one of the three children of Loki and Angrboda, which grew so large that it could encircle the world and grasp its tail in its teeth.

It is a common belief among indigenous people of the tropical lowlands of South America that waters at the edge of the world-disc are encircled by a snake, often an anaconda, biting its own tail.

[43][44] For example, according to the myths of the Australian Karajarri, the mythical Bagadjimbiri brothers established all of the Karadjeri's customs, including the position in which they stand while urinating.

For example, the Austrian scholar Johann Georg von Hahn tried to identify a common structure underlying Aryan hero stories.

Examples include Lamia of Greek mythology, a woman who became a child-eating monster after her children were destroyed by Hera, upon learning of her husband Zeus' trysts.

The myth of Baxbaxwalanuksiwe, in Hamatsa society of the Kwakwaka'wakw indigenous tribe, tells of a man-eating giant, who lives in a strange house with red smoke emanating from its roof.

Most human civilizations - India, China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Maya, and Inca, among others - based their culture on complex systems of astrology, which provided a link between the cosmos with the conditions and events on earth.

Spirits are thought to travel between worlds, or layers of existence in such traditions, usually along an axis such as a giant tree, a tent pole, a river, a rope or mountains.

Vedanta (Advaita Vedanta), Ayyavazhi, shamanism, Hermeticism, Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Kashmir Shaivism, Sant Mat/Surat Shabd Yoga, Sufism, Druze, Kabbalah, Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Rosicrucianism (Esoteric Christian), Eckankar, Ascended Master Teachings, etc.—which propound the idea of a whole series of subtle planes or worlds or dimensions which, from a center, interpenetrate themselves and the physical planet in which we live, the solar systems, and all the physical structures of the universe.

This interpenetration of planes culminates in the universe itself as a physical structured, dynamic and evolutive expression emanated through a series of steadily denser stages, becoming progressively more material and embodied.