Complex geometry

Application of transcendental methods to algebraic geometry falls in this category, together with more geometric aspects of complex analysis.

Because of the blend of techniques and ideas from various areas, problems in complex geometry are often more tractable or concrete than in general.

For example, the classification of complex manifolds and complex algebraic varieties through the minimal model program and the construction of moduli spaces sets the field apart from differential geometry, where the classification of possible smooth manifolds is a significantly harder problem.

Additionally, the extra structure of complex geometry allows, especially in the compact setting, for global analytic results to be proven with great success, including Shing-Tung Yau's proof of the Calabi conjecture, the Hitchin–Kobayashi correspondence, the nonabelian Hodge correspondence, and existence results for Kähler–Einstein metrics and constant scalar curvature Kähler metrics.

These results often feed back into complex algebraic geometry, and for example recently the classification of Fano manifolds using K-stability has benefited tremendously both from techniques in analysis and in pure birational geometry.

It is often a source of examples in other areas of mathematics, including in representation theory where generalized flag varieties may be studied using complex geometry leading to the Borel–Weil–Bott theorem, or in symplectic geometry, where Kähler manifolds are symplectic, in Riemannian geometry where complex manifolds provide examples of exotic metric structures such as Calabi–Yau manifolds and hyperkähler manifolds, and in gauge theory, where holomorphic vector bundles often admit solutions to important differential equations arising out of physics such as the Yang–Mills equations.

Complex geometry additionally is impactful in pure algebraic geometry, where analytic results in the complex setting such as Hodge theory of Kähler manifolds inspire understanding of Hodge structures for varieties and schemes as well as p-adic Hodge theory, deformation theory for complex manifolds inspires understanding of the deformation theory of schemes, and results about the cohomology of complex manifolds inspired the formulation of the Weil conjectures and Grothendieck's standard conjectures.

On the other hand, results and techniques from many of these fields often feed back into complex geometry, and for example developments in the mathematics of string theory and mirror symmetry have revealed much about the nature of Calabi–Yau manifolds, which string theorists predict should have the structure of Lagrangian fibrations through the SYZ conjecture, and the development of Gromov–Witten theory of symplectic manifolds has led to advances in enumerative geometry of complex varieties.

For example, whereas smooth manifolds admit partitions of unity, collections of smooth functions which can be identically equal to one on some open set, and identically zero elsewhere, complex manifolds admit no such collections of holomorphic functions.

Indeed, this is the manifestation of the identity theorem, a typical result in complex analysis of a single variable.

In some sense, the novelty of complex geometry may be traced back to this fundamental observation.

In contrast, the possible singular behaviour of a continuous real-valued function is much more difficult to characterise.

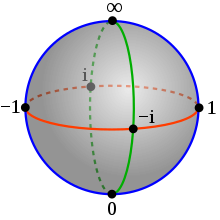

of complex projective space that is, in the same way, locally given by the zeroes of a finite collection of holomorphic functions on open subsets of

One may similarly define an affine complex algebraic variety to be a subset

To define a projective complex algebraic variety, one requires the subset

We say a complex variety is smooth or non-singular if it's singular locus is empty.

Complex manifolds may be studied from the perspective of differential geometry, whereby they are equipped with extra geometric structures such as a Riemannian metric or symplectic form.

Serre's GAGA theorem asserts that projective complex analytic varieties are actually algebraic.

Whilst this is not strictly true for affine varieties, there is a class of complex manifolds that act very much like affine complex algebraic varieties, called Stein manifolds.

Examples of Stein manifolds include non-compact Riemann surfaces and non-singular affine complex algebraic varieties.

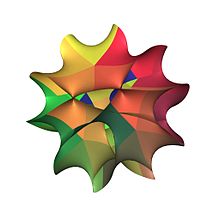

admits a Kähler metric with vanishing Ricci curvature, and this may be taken as an equivalent definition of Calabi–Yau.

Examples of Calabi–Yau manifolds are given by elliptic curves, K3 surfaces, and complex Abelian varieties.

This makes toric varieties a particularly attractive test case for many constructions in complex geometry.

Examples of toric varieties include complex projective spaces, and bundles over them.

For example, in differential geometry, many problems are approached by taking local constructions and patching them together globally using partitions of unity.

For example, famous problems in the analysis of several complex variables preceding the introduction of modern definitions are the Cousin problems, asking precisely when local meromorphic data may be glued to obtain a global meromorphic function.

Since sheaf cohomology measures obstructions in complex geometry, one technique that is used is to prove vanishing theorems.

For example, the Hirzebruch-Riemann-Roch theorem, a special case of the Atiyah-Singer index theorem, computes the holomorphic Euler characteristic of a holomorphic vector bundle in terms of characteristic classes of the underlying smooth complex vector bundle.

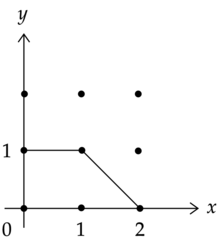

Due to the rigid nature of complex manifolds and varieties, the problem of classifying these spaces is often tractable.

, which is a non-negative integer counting the number of holes in the given compact Riemann surface.