Composition of the Torah

The composition of the Torah (or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) was a process that involved multiple authors over an extended period of time.

[1] Jewish tradition held that all five books were originally written by Moses in the 2nd millennium BCE, but since the 17th century modern scholars have rejected Mosaic authorship.

[4][5][6] By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.

[7] Other scholars, such as Richard Elliott Friedman or Joel S. Baden, support a revised version of the documentary hypothesis, holding that the Torah was composed by using four different sources—Yahwist, Elohist, Priestly, and Deuteronomist—that were combined into one in the Persian period in Yehud.

[11] The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, was likely completed during the Persian period (539–333 BCE).

[17][18] In addition, early non-biblical sources, such as the Letter of Aristeas, indicate that the Torah was first translated into Greek in Alexandria under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–247 BCE).

In Book 40 of Diodorus Siculus's Library, an ancient encyclopedia compiled from a variety of quotations from older documents, there is a passage that refers to a written Jewish law passed down from Moses.

[21] Scholars have traditionally attributed the passage to the late 4th-century Greek historian Hecataeus of Abdera, which, if correct, would imply that the Torah must have been composed in some form before 315 BCE.

Russell Gmirkin has argued that the passage is in fact a quote from Theophanes of Mytilene, a first-century BCE Roman biographer cited earlier in Book 40, who in turn used Hecataeus along with other sources.

[23][24] The papyri also document the existence of a small Jewish temple at Elephantine, which possessed altars for incense offerings and animal sacrifices, as late as 411 BCE.

[27] By contrast, most scholars explain this data by theorizing that the Elephantine Jews represented an isolated remnant of Jewish religious practices from earlier centuries,[24] or that the Torah had only recently been promulgated at that time.

[36] Ian Young and Martin Ehrensvärd maintain that even some texts that were certainly written during the post-exilic period, such as the Book of Haggai, lack features distinctive of Late Biblical Hebrew.

[37] Summing up these problems, Young has argued that "none of the linguistic criteria used to date [biblical] texts either early or late is strong enough to compel scholars to reconsider an argument made on non-linguistic grounds.

[44] Similarly, many scholars associate the Priestly source with the Book of the Law brought to the people of Israel by Ezra upon his return from exile in Babylonia in 458 BCE, as described in Nehemiah 8–10.

These critics stress that the historicity of the Josiah and Ezra narratives cannot be independently established outside the Hebrew Bible, and that archaeological evidence generally does not support the occurrence of a radical centralizing religious reform in the 7th century as described in 2 Kings.

[46] In the influential book In Search of 'Ancient Israel': A Study in Biblical Origins, Philip Davies argued that the Torah was likely promulgated in its final form during the Persian period, when the Judean people were governed under the Yehud Medinata province of the Achaemenid Empire.

[47][48] Davies points out that the Persian empire had a general policy of establishing national law codes and consciously creating an ethnic identity among its conquered peoples in order to legitimate its rule, and concludes that this is the most likely historical context in which the Torah could have been published.

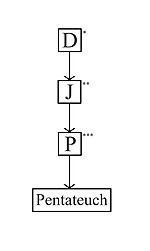

[55] While Gmirkin accepts the conventional stratification of the Pentateuch into sources such as J, D, and P, he believes that they are best understood as reflecting the different social strata and beliefs of the Alexandrian authors, rather than as independent writers separated by long periods of time.

[58] John Van Seters criticized Gmirkin's work in a 2007 book review, arguing that Berossus and Genesis engages in a straw man fallacy by attacking the documentary hypothesis without seriously addressing more recent theories of Pentateuchal origins.

[73] While the classical documentary hypothesis posited that the Priestly material constituted an independent document which was compiled into the Pentateuch by a later redactor, most contemporary scholars now view P as a redactional layer, or commentary, on the Yahwistic and Deuteronomistic sources.

[75] Avi Hurvitz, for example, has forcefully argued on linguistic grounds that P represents an earlier form of the Hebrew language than what is found in both Ezekiel and Deuteronomy, and therefore pre-dates both of them.

[76][33] These scholars often claim that the late-dating of P is due in large part to a Protestant bias in biblical studies which assumes that "priestly" and "ritualistic" material must represent a late degeneration of an earlier, "purer" faith.

[35] The Deuteronomist source is responsible for the core chapters (12–26) of Book of Deuteronomy, containing the Deuteronomic Code,[77] and its composition is generally dated between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE.

It includes, among other pericopes, the departure from Sinai, the story of the spies who are afraid of the giants in Canaan, and the refusal of the Israelites to enter the Promised Land – which then brings on the wrath of Yahweh, who condemns them to wander in the wilderness for the next forty years.

[1] In 1780 Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and exegete Jean Astruc's "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the Jehovist ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the Elohist ("E").

[104] Van Seters and Schmid both forcefully argued, to the satisfaction of most scholars, that the Yahwist source could not be dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE) as posited by the documentary hypothesis.

[4][5][6] By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.

[11] The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses.

[110] The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the Persian period (539–333 BCE).

Mid-twentieth century scholars like Gerhard von Rad and Martin Noth argued that the transmission of Pentateuchal narratives occurred primarily through oral tradition.

- J: Yahwist (10th–9th century BCE) [ 97 ] [ 98 ]

- E: Elohist (9th century BCE) [ 97 ]

- Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- P*: Priestly (6th–5th century BCE) [ 64 ] [ 98 ]

- D†: Deuteronomist

- R: redactor

- DH: Deuteronomistic history (books of Joshua , Judges , Samuel , Kings )

| * | Independent document, c. 620 BCE. |

| ** | Response to D, c. 540 BCE. |

| *** | Largely a redactor of J, c. 400 BCE. |