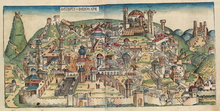

Babylonian captivity

[1] Archaeological studies have revealed that, although the city of Jerusalem was utterly destroyed, other parts of Judah continued to be inhabited during the period of the exile.

This decision led to the establishment of a sizable Jewish community in Mesopotamia known as the golah (dispersal), which persisted until modern times.

Egypt, fearing the sudden rise of the Neo-Babylonian empire, seized control of Assyrian territory up to the Euphrates river in Syria, but Babylon counter-attacked.

After the defeat of Pharaoh Necho's army by the Babylonians at Carchemish in 605 BCE, Jehoiakim began paying tribute to Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon.

[11] The city fell on 2 Adar (March 16) 597 BCE,[12] and Nebuchadnezzar pillaged Jerusalem and its Temple and took Jeconiah, his court and other prominent citizens (including the prophet Ezekiel) back to Babylon.

[13] Jehoiakim's uncle Zedekiah was appointed king in his place, but the exiles in Babylon continued to consider Jeconiah as their Exilarch, or rightful ruler.

Some time later, a surviving member of the royal family assassinated Gedaliah and his Babylonian advisors, prompting many refugees to seek safety in Egypt.

[19][20] One of the tablets refers to food rations for "Ya’u-kīnu, king of the land of Yahudu" and five royal princes, his sons.

[21] Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonian forces returned in 589 BCE and rampaged through Judah, leaving clear archaeological evidence of destruction in many towns and settlements there.

Taking the different biblical numbers of exiles at their highest, 20,000, this would mean that perhaps 25% of the population had been deported to Babylon, with the remaining majority staying in Judah.

[18]: 306 Although Jerusalem was destroyed, with large parts of the city remaining in ruins for 150 years, numerous other settlements in Judah continued to be inhabited, with no signs of disruption visible in archaeological studies.

Biblical scholar Niels Peter Lemche suggests that the exiled Judeans experienced a lifestyle scarcely less prosperous than what they were accustomed to in their homeland.

For example, exiled Jewish leaders were suspected of national disloyalty and were reduced to peasantry, where they worked in agriculture and building projects and performed simple tasks such as farming, shepherding and fishing.

[25] Professor Lester L. Grabbe asserted that the "alleged decree of Cyrus" regarding Judah, "cannot be considered authentic", but that there was a "general policy of allowing deportees to return and to re-establish cult sites".

[35] This period saw the last high point of biblical prophecy in the person of Ezekiel, followed by the emergence of the central role of the Torah in Jewish life.

"[37] Notably, the period also saw the theological transition of the ancient Israelite religion among the captives from a monolatrous to a monotheistic faith system.

After this time, there were always sizable numbers of Jews living outside the Land of Israel; thus, it also marks the beginning of the "Jewish diaspora", unless this is considered to have begun with the Assyrian captivity.