Conestoga wagon

Conestoga wagon usage likely declined as a result of displacement by canals and railroads in the 19th century, which proved to be more efficient means of transporting goods.

In November of the same year, Logan established a store for selling hardware and household goods to German settlers and Native Americans in Conestoga.

Logan then purchased what he called a "Conestogoe Waggon" from James Hendricks on December 31, 1717, thus making this the earliest known mention of the wagon name.

[4] Advertisements in The Pennsylvania Gazette indicate that the former term saw common usage by February 5, 1750, for a Philadelphia tavern named "The Sign of the Conestogoe Wagon".

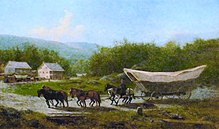

[9] In comparison, American western frontier covered wagons were often transported by oxen instead of horses, but travelers tended to prefer the latter option.

It is boat-shaped in terms of both crosswise (horizontal) and lengthwise (vertical) dimensions, thus ensuring the ability for sagging, or curving downwards in the middle, during movements through hills and valleys so that the loads remained centered.

Its designs were meant to replicate large-sized watercrafts that serve the dual purposes of carrying heavy quantities of goods and withstanding hostile environmental conditions such as currents.

Six to twelve sloping hooplike hickory bows or "tilts",[16] reaching individual grounded heights of 12 ft (3.7 m), are arched over the wagon's bed to hold the white canvas sheet that covers them.

The canvas, a cloth made from hemp fiber, was tied down to both sides of the wagon body but were left overhanging at both its front and rear ends.

The rear portion is made up of similar components, but instead of a tongue, it has a coupling pole (a beam connecting the front and back wagon axles).

The left front hound may also hold an iron sheath for an axe that wagoners can use to cut through wood obstacles or make new tongues and axletrees.

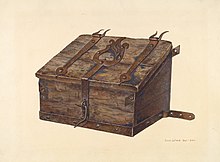

[27] Conestoga wagons may also be equipped with water barrels on the side, toolboxes for wagon-fixing, and a pot of tar for keeping the wheels moving.

[29] Conestoga wagon production depended largely on the labors of blacksmiths and similar occupations since the colonial era of the United States, coinciding with increased land colonization and the rise of the American iron industry.

[32] By 1720, farm wagons were already put into usage within the British colony of Pennsylvania as they carried merchandise from Philadelphia to Lancaster county in exchange for furs.

[4] In the mid-18th century, the German immigrants of Lancaster County produced their own Conestoga wagons for hauling crops elsewhere and for traveling on dirt roads.

[34] Major-General Edward Braddock arrived to North America in February 1755 to carry out his role as commander-in-chief of the British forces during the French and Indian War.

[35] Colonel Sir John St. Clair informed Braddock about settlers at the Blue Ridge Mountains who were running provisions and stores, expressing confidence that by early May 1755, they would have 200 wagons and 1,500 pack horses ready for deployment into Fort Cumberland.

The major-general was aggravated in reaction to the underwhelming resources and wanted to shut down the expedition, but he later commissioned Benjamin Franklin to gather some 150 wagons and 1,500 pack horses from the locals.

[36] According to the British Army officer Robert Orme, the wagons, artillery, and carrying horses were placed into three different divisions that were each overseen by an appointed superior.

Most of the wagons at Dunbar's Camp were burned by the British to prevent the French and Native Americans from seizing their materials as they anticipated pursuit by the enemy forces.

[17][7] As the main terrestrial vehicles of transport in North America, they frequently hauled farm goods from rural areas into towns and cities in exchange for other manufactured commodities.

[38] In the 18th century of the United States, the Conestoga wagon was the most popular transport vehicle of the American frontier, and as many as one hundred of them traveled in individual groups, extending in geographical range from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Augusta, Georgia.

[43] It was used to some extent for travel to the western frontier, but it was generally too heavy, required too many draft animals for hauling, and was an expensive vehicle to build or purchase.

[39] The perception of Conestoga wagons being the preferred vehicle of choice for traveling westward in North America is seemingly the result of them being better-represented in literature and media compared to the smaller prairie schooners.

Tavern keepers, generally influential men of their communities, made profits from selling liquor and meals to them, but their revenue mainly came from overnight stays, which would have cost less than $1.75.

[50] The Conestoga wagon's extended period of use in North America gradually declined in the latter half of the early 19th century as technological change ushered in more practical alternatives.

This was especially true in the state where the covered wagons had originated, Pennsylvania, as the introduction and spread of canals provided a cheaper and faster way to transport goods.

[52] Despite the replacement not only of most wagons but also of the short-lived Pony Express mail service by more technologically advanced modes of transport, the US horse population did not experience a corresponding decline in numbers.

The Nissen Wagon, originating in North Carolina,[21] was still a popular transport vehicle throughout the 19th century; contemporaneous production numbers reflect that high demand.

[58] In the modern day, the legacy of Conestoga wagons declined mostly to books, paintings, and historical artifacts held by museums and private collections.