Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism,[1] is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy (humanistic or rationalistic), religion, theory of government, or way of life.

[12] The worldly concern of Confucianism rests upon the belief that human beings are fundamentally good, and teachable, improvable, and perfectible through personal and communal endeavor, especially self-cultivation and self-creation.

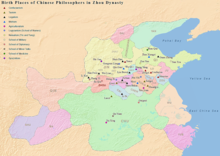

Confucianism was initiated by the disciples of Confucius, developed by Mencius (c. 372–289 BC) and inherited by later generations, undergoing constant transformations and restructuring since its establishment, but preserving the principles of humaneness and righteousness at its core.

[26] Traditionally, Confucius was thought to be the author or editor of the Five Classics which were the basic texts of Confucianism, all edited into their received versions around 500 years later by Imperial Librarian Liu Xin.

[29] Yao suggests that most modern scholars hold the "pragmatic" view that Confucius and his followers did not intend to create a system of classics, but nonetheless "contributed to their formation".

[34] Joël Thoraval studied Confucianism as a diffused civil religion in contemporary China, finding that it expresses itself in the widespread worship of five cosmological entities: Heaven and Earth (地; dì), the sovereign or the government (君; jūn), ancestors (親; qīn), and masters (師; shī).

"Yin and yang are the invisible and visible, the receptive and the active, the unshaped and the shaped; they characterise the yearly cycle (winter and summer), the landscape (shady and bright), the sexes (female and male), and even sociopolitical history (disorder and order).

The scholar Ronnie Littlejohn warns that tian was not to be interpreted as a personal God comparable to that of the Abrahamic faiths, in the sense of an otherworldly or transcendent creator.

[46] Regarding personal gods (shen, energies who emanate from and reproduce Tian) enliving nature, in the Analects Confucius says that it is appropriate (yi) for people to worship (敬; jìng) them,[50] although only through proper rites (li), implying respect of positions and discretion.

[55] Feuchtwang explains that the difference between Confucianism and Taoism primarily lies in the fact that the former focuses on the realisation of the starry order of Heaven in human society, while the latter on the contemplation of the Dao which spontaneously arises in nature.

[57] As explained by Stephan Feuchtwang, the order coming from Heaven preserves the world, and has to be followed by humanity finding a "middle way" between yin and yang forces in each new configuration of reality.

Loyalty (忠; zhōng) is particularly relevant for the social class to which most of Confucius's students belonged, because the most important way for an ambitious young scholar to become a prominent official was to enter a ruler's civil service.

Examples of such xiaoren individuals may range from those who continually indulge in sensual and emotional pleasures all day to the politician who is interested merely in power and fame; neither sincerely aims for the long-term benefit of others.

[3] John C. Didier and David Pankenier relate the shapes of both the ancient Chinese characters for Di and Tian to the patterns of stars in the northern skies, either drawn, in Didier's theory by connecting the constellations bracketing the north celestial pole as a square,[81] or in Pankenier's theory by connecting some of the stars which form the constellations of the Big Dipper and broader Ursa Major, and Ursa Minor (Little Dipper).

Communication with the divine no longer was an exclusive privilege of the Zhou royal house, but might be bought by anyone able to afford the elaborate ceremonies and the old and new rites required to access the authority of Tian.

As central political authority crumbled in the wake of the collapse of the Western Zhou, the population lost faith in the official tradition, which was no longer perceived as an effective way to communicate with Heaven.

Confucius saw an opportunity to reinforce values of compassion and tradition into society, with the intended goal of reconstructing what he believed to be a lost perfect moral order of high antiquity.

[108] Confucianism, despite supporting the importance of obeying national authority, places this obedience under absolute moral principles that curbed the willful exercise of power, rather than being unconditional.

"[116]: 151–179 Bell and Wang argue that this combination conserves the main advantages of democracy—involving the people in public affairs at the local level, strengthening the legitimacy of the system, forcing some degree of direct accountability, etc.—while preserving the broader meritocratic character of the regime.

[118] Jiang's aim is to construct a legitimacy that will go beyond what he sees as the atomistic, individualist, and utilitarian ethos of modern democracies and ground authority in something sacred and traditional.

[114]: 76–78 Others, like Jiang Qing, defend a model in which superiors decide who gets promoted; this method is in line with more traditionalist strands of Confucian political thought, which place a greater emphasis on strict hierarchies and epistemic paternalism—that is, the idea that older and more experienced people know more.

Against defenders of political meritocracy, Tseng claims that the fusion of Confucian and democratic institutions can conserve the best of both worlds, producing a more communal democracy which draws on a rich ethical tradition, addresses abuses of power, and combines popular accountability with a clear attention to the cultivation of virtue in elites.

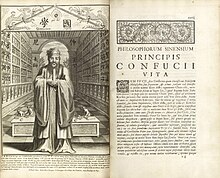

[125] Translations of Confucian texts influenced European thinkers of the period,[126] particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western civilization.

[128] He praised Confucian ethics and politics, portraying the sociopolitical hierarchy of China as a model for Europe:[128] Confucius has no interest in falsehood; he did not pretend to be prophet; he claimed no inspiration; he taught no new religion; he used no delusions; flattered not the emperor under whom he lived ...From the late 17th century onwards a whole body of literature known as the Han Kitab developed amongst the Hui Muslims of China who infused Islamic thought with Confucianism.

These scholars have held that, if not for Confucianism's influence on these cultures, many of the people of the East Asia region would not have been able to modernise and industrialise as quickly as Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and even China have done.

Though in his own day, Confucius had rejected the practice of Martial Arts (with the exception of Archery), he did serve under rulers who used military power extensively to achieve their goals.

Confucius and Confucianism were opposed or criticised from the start, including Laozi's philosophy and Mozi's critique, and Legalists such as Han Fei ridiculed the idea that virtue would lead people to be orderly.

For example, South Korean writer Kim Kyong-il wrote a book in 1998 entitled "Confucius Must Die For the Nation to Live" (공자가 죽어야 나라가 산다, gongjaga jug-eoya naraga sanda).

[138] Starting from the Han period, Confucians began to teach that a virtuous woman was supposed to follow the males in her family: the father before her marriage, the husband after she marries, and her sons in widowhood.

[153][154] But using a broader definition, such as Frederick Streng's characterisation of religion as "a means of ultimate transformation",[155] Confucianism could be described as a "sociopolitical doctrine having religious qualities".