Hanfu

[30] An example of a Shang dynasty attire can be seen on an anthropomorphic jade figurine excavated from the Tomb of Fu Hao in Anyang, which shows a person wearing a long narrow-sleeved yi with a wide band covering around waist, and a skirt underneath.

[32]: 16 Other markers of status included the fabric materials, the shape, size, colour of the clothing, the decorative pattern, the length of a skirt, the wideness of a sleeve, and the degree of ornamentation.

[32] The mianfu, bianfu, and xuanduan all consisted of four separate parts: a skirt underneath, a robe in the middle, a bixi on top, and a long cloth belt dadai (Chinese: 大带).

This reform, commonly referred to as Hufuqishe, required all Zhao soldiers to wear the Hufu-style uniforms of the Donghu, Linhu and Loufan people in battle to facilitate fighting capability.

[32][34][55] Based on the archaeological artifacts dating from the Eastern Zhou dynasty, ordinary men, peasants and labourers, were wearing a long youren yi with narrow-sleeves, with a narrow silk band called sitao (Chinese: 丝套) being knotted at the waist over the top.

[2]: 24 [66]: 183 In court, the officials wore hats, loose robes with carving knives hanging from the waist, holding hu, and stuck ink brush between head and ears.

[61] Typical women attire during this period is the guiyi, a wide-sleeved paofu adorned with xian (髾; long swirling silk ribbons) and shao (襳; a type of triangular pieces of decorative embroidered-cloth) on the lower hem of the robe that hanged like banners and formed a "layered effect".

[77] Leather boots (靴, xue), quekua (缺胯; an open-collared robe with tight sleeves; it cannot cover the undershirt), hood and cape ensemble were introduced by northern nomads in China.

[32] Near the areas of the Yellow River, the popularity of the ethnic minorities' hufu was high, almost equal to the Han Chinese clothing, in the Sixteen Kingdoms and the Northern and Southern dynasties period.

[54][99] Some of the female servants depicted from the tomb murals of Xu Xianxiu are wearing what appears to be Sogdian dresses, which tend to be associated with dancing girls and low-status entertainers during this period, while the ladies-in-waiting of Xu Xianxiu's wife are wearing narrow-sleeved clothing which look more closely related to Xianbei-style or Central Asian-style clothing; yet this Xianbei style of attire is different from the depictions of Xianbei-style attire worn before 500 AD.

Where previously Chinese women had been restricted by the old Confucian code to closely wrapped, concealing outfits, female dress in the Tang dynasty gradually became more relaxed, less constricting and even more revealing.

[134] The influence of hufu eventually faded after the High Tang period, and women's clothing gradually regained a broad, loose fitting, and more traditional Han style.

[50] Palace ladies searched for guidance in the Rites of Zhou on how to dress accordingly to ceremonial events and carefully chose ornaments which were graded for each occasion based on the classic rituals.

[135]: 32–59 They also banned people, except for drama actors, from wearing Jurchen and Khitan diaodun (釣墩; a type of lower garment where the socks and trousers were connected to each other) due to its foreign ethnic nature.

[153] Burial clothing and tomb paintings in the southern territories of the Yuan dynasty also show that women wore the Song-style attire, which looked slimmer when compared to the Mongol court robe.

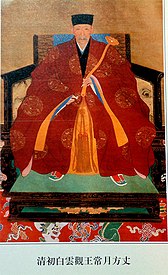

[155] The emperors tend to wear yellow satin gown with dragon designs, jade belts, and yishanguan (翼善冠; philanthropy crown, with wings folded upwards).

[159][164] In the middle of the Ming dynasty, the interlocking buttons were often paired with the upper garment with standing collar; it was commonly used by women partially because they wanted to cover their bodies to show modesty and preserve their chastity and because of the cold climate period.

[167] A royal edict was issued by Vietnam in 1474 forbidding Vietnamese from adopting foreign languages, hairstyles and clothes like that of the Lao, Champa or the "Northerners" which referred to the Ming.

[109]: 2–3 [165] The aim of this edict was made to preserve the Manchu identity once again, but at the same time, it also attempted to align the image of the emperor with Confucian ideas and codes of behaviours and manners.

[188][189] Even after a decade following tifayifu policy implementation, Han Chinese still resisted against the order of shaving the hair and changing into Manchu clothing frequently.

[195][191] Those who were exempted from such policies were women, children, Buddhist and Taoist monks, and Qing dynasty rebels; moreover, men in their living had to wear Manchu-clothing, but they could be buried in Hanfu after their death.

In an attempt to restore the identity of the Han Chinese, the Taiping rebels established their own clothing system, which introduced dedicated uniforms and features of Hakka fashion, removing characteristics of qizhuang such as the matixiu or horse-hoof cuffs and hats used by the Qing.

[200] After the Qing dynasty was toppled in the 1911 Xinhai revolution, the Taoist dress and topknot was adopted by the ordinary gentry and "Society for Restoring Ancient Ways" (Fuguhui) on the Sichuan and Hubei border where the White Lotus and Gelaohui operated.

[211] After death, their hair could also be combed into a topknot similar to the ones worn by the Han Chinese in Ming; a practice which was observed by the Europeans;[200] men who were wealthy but held no official rank were allowed to be buried in a deep-blue silk shenyi which was edged with bright blue or white band.

[27]: 257–265 Since the 20th century, hanfu and hanfu-style clothing has been used frequently as ancient costumes in Chinese and foreign television series, films and other forms of entertainment media, and was widely popularized since the late 1980s dramas.

[227][228] Modern Taoist monks and Taoism practitioners continue to style their long hair into a touji (頭髻; a topknot hairstyle) and wear traditional clothing.

[18] On March 8, 2021, the magazine Vogue published an article on modern hanfu defining it as a "type of dress from any era when Han Chinese ruled" and reported that the styles based on the Tang, Song, Ming periods were the most popular.

The typical types of male headwear are called jin (巾) for soft caps, mao (帽) for stiff hats and guan for formal headdress.

This was due to Confucius' teaching "Shenti fa fu, shou zhu fumu, bu gan huishang, xiaozhi shi ye (身體髮膚,受諸父母,不敢毀傷,孝之始也)" – which can be roughly translated as 'My body, hair and skin are bestowed by my father and mother, I dare not damage any of them, as this is the least I can do to honor and respect my parents'.

Such strict "no-cutting" hair tradition was implemented all throughout Han Chinese history since Confucius' time up until the end of Ming dynasty (1644 CE), when the Qing Prince Dorgon forced the male Han people to adopt the hairstyle of Manchu men, which was shave their foreheads bald and gather the rest of the hair into the queue to show that they submitted to Qing authority, the so-called "Queue Order" (薙髮令).