Congo Crisis

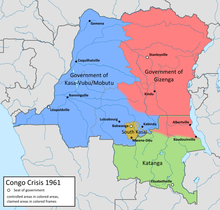

Amid continuing unrest and violence, the United Nations deployed peacekeepers, but UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld refused to use these troops to help the central government in Léopoldville fight the secessionists.

Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, the charismatic leader of the largest nationalist faction, reacted by calling for assistance from the Soviet Union, which promptly sent military advisers and other support.

Mobutu, at that time Lumumba's chief military aide and a lieutenant-colonel in the army, broke this deadlock with a coup d'état, expelled the Soviet advisors and established a new government effectively under his own control.

With Katanga and South Kasai back under the government's control, a reconciliatory compromise constitution was adopted and the exiled Katangese leader, Moïse Tshombe, was recalled to head an interim administration while fresh elections were organised.

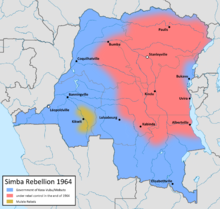

Government forces gradually retook territory and, in November 1964, Belgium and the United States intervened militarily in Stanleyville to recover hostages from Simba captivity.

On many occasions, the interests of the government and private enterprise became closely tied and the state helped companies with strikebreaking and countering other efforts by the indigenous population to better their lot.

[9] The country was split into nesting, hierarchically organised administrative subdivisions, and run uniformly according to a set "native policy" (politique indigène)—in contrast to the British and the French, who generally favoured the system of indirect rule whereby traditional leaders were retained in positions of authority under colonial oversight.

Large numbers of white immigrants who moved to the Congo after the end of World War II came from across the social spectrum, but were nonetheless always treated as superior to black people.

The split divided the party's support base into those who remained with Lumumba, chiefly in the Stanleyville region in the north-east, and those who backed the MNC-K, which became most popular around the southern city of Élisabethville and among the Luba ethnic group.

[17] August de Schryver, the Minister of the Colonies, launched a high-profile Round Table Conference in Brussels in January 1960, with the leaders of all the major Congolese parties[which?]

[28] Belgians began campaigning against Lumumba, whom they wanted to marginalise; they accused him of being a communist and, hoping to fragment the nationalist movement, supported rival, ethnic-based parties like CONAKAT.

[29] Many Belgians hoped that an independent Congo would form part of a federation, like the French Community or Britain's Commonwealth of Nations, and that close economic and political association with Belgium would continue.

In a ceremony at the Palais de la Nation in Léopoldville, King Baudouin gave a speech in which he presented the end of colonial rule in the Congo as the culmination of the Belgian "civilising mission" begun by Leopold II.

[41] The international press expressed shock at the apparent sudden collapse of order in the Congo, as the world view of the Congolese situation prior to independence—due largely to Belgian propaganda—was one of peace, stability, and strong control by the authorities.

This action prompted renewed attacks on whites across the country, while Belgian forces entered other towns and cities, including Léopoldville, and clashed with Congolese troops.

UMHK was largely owned by the Société Générale de Belgique, a prominent holding company based in Brussels that had close ties to the Belgian government.

[60] Ostensibly in order to resolve the deadlock, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu launched a bloodless coup and replaced both Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba with a College of Commissionaires-General (Collège des Commissaires-généraux) consisting of a panel of university graduates, led by Justin Bomboko.

A meeting of the UN Security Council was called on 7 December 1960 to consider Soviet demands that the UN seek Lumumba's immediate release, his restoration to the head of the Congolese government and the disarming of Mobutu's forces.

[78][e] ONUC's claim to impartiality was undermined in mid-September when a company of Irish UN troops were captured by numerically superior Katangese forces following a six-day siege in Jadotville.

[81] Katanga released the captured Irish soldiers in mid-October as part of a cease-fire deal in which ONUC agreed to pull its troops back—a propaganda coup for Tshombe.

[83] On 5 October 1962, central government troops again arrived in Bakwanga to support the mutineers and help suppress the last Kalonjist loyalists, marking the end of South Kasai's secession.

The resolution "completely rejected" Katanga's claim to statehood and authorised ONUC troops to use all necessary force to "assist the Central Government of the Congo in the restoration and maintenance of law and order".

Faced with international pressure, Tshombe signed the Kitona Declaration in December 1961 in which he agreed in principle to accept the authority of the central government and state constitution and to abandon any claim to Katangese independence.

[91] Although personally capable, and supported as an anti-communist by Western powers, Tshombe was denounced by other African leaders such as King Hassan II of Morocco as an imperialist puppet for his role in the Katangese secession.

[96] The rebels, who called themselves "Simbas" (from the Kiswahili word for "lion"), had a populist but vague ideology, loosely based on communism, which prioritised equality and aimed to increase overall wealth.

[117] Pockets of Simba resistance continued to hold out in the eastern Congo, most notably in South Kivu, where Laurent-Désiré Kabila led a Maoist cross-border insurgency which lasted until the 1980s.

[127] Subsequent loss of faith in central government is one of the reasons that the Congo has been labeled as a failed state, and has contributed violence by factions advocating ethnic and localised federalism.

[133] In particular, Lumumba's murder is viewed in the context of the memory as a symbolic moment in which the Congo lost its dignity in the international realm and the ability to determine its future, which has since been controlled by the West.

[136] In Belgium, allegations of Belgian complicity in the killing of Lumumba led to a state-backed inquiry and subsequent official apology in 2001 for "moral responsibility", though not direct involvement, in the assassination.

[152] Unlike Katanga, Biafra achieved limited official international recognition and rejected the support of Western multinational companies involved in the local oil industry.