Conic section

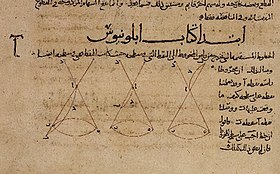

The ancient Greek mathematicians studied conic sections, culminating around 200 BC with Apollonius of Perga's systematic work on their properties.

In analytic geometry, a conic may be defined as a plane algebraic curve of degree 2; that is, as the set of points whose coordinates satisfy a quadratic equation in two variables which can be written in the form

The conic sections have been studied for thousands of years and have provided a rich source of interesting and beautiful results in Euclidean geometry.

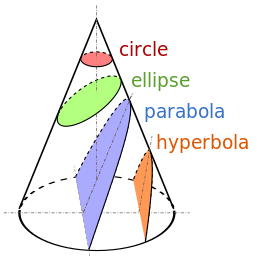

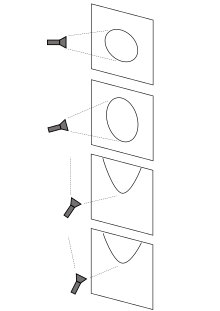

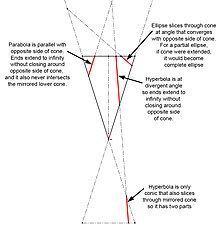

If the cutting plane is parallel to exactly one generating line of the cone, then the conic is unbounded and is called a parabola.

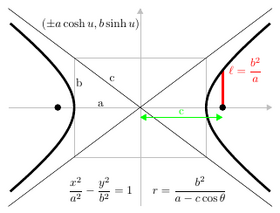

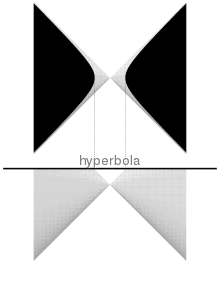

In the remaining case, the figure is a hyperbola: the plane intersects both halves of the cone, producing two separate unbounded curves.

[4] A proof that the above curves defined by the focus-directrix property are the same as those obtained by planes intersecting a cone is facilitated by the use of Dandelin spheres.

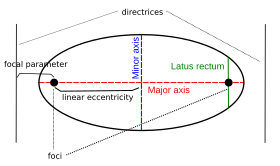

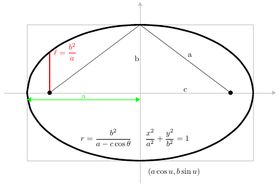

In addition to the eccentricity (e), foci, and directrix, various geometric features and lengths are associated with a conic section.

The principal axis is the line joining the foci of an ellipse or hyperbola, and its midpoint is the curve's center.

When an ellipse or hyperbola are in standard position as in the equations below, with foci on the x-axis and center at the origin, the vertices of the conic have coordinates (−a, 0) and (a, 0), with a non-negative.

After introducing Cartesian coordinates, the focus-directrix property can be used to produce the equations satisfied by the points of the conic section.

[7] By means of a change of coordinates (rotation and translation of axes) these equations can be put into standard forms.

If the conic is non-degenerate, then:[14] In the notation used here, A and B are polynomial coefficients, in contrast to some sources that denote the semimajor and semiminor axes as A and B.

The polar form of the equation of a conic is often used in dynamics; for instance, determining the orbits of objects revolving about the Sun.

This is important for many applications, such as aerodynamics, where a smooth surface is required to ensure laminar flow and to prevent turbulence.

It is believed that the first definition of a conic section was given by Menaechmus (died 320 BC) as part of his solution of the Delian problem (Duplicating the cube).

This may account for why Apollonius considered circles a fourth type of conic section, a distinction that is no longer made.

[34][35] A century before the more famous work of Khayyam, Abu al-Jud used conics to solve quartic and cubic equations,[36] although his solution did not deal with all the cases.

[38][39] Johannes Kepler extended the theory of conics through the "principle of continuity", a precursor to the concept of limits.

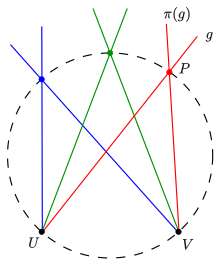

[40] Girard Desargues and Blaise Pascal developed a theory of conics using an early form of projective geometry and this helped to provide impetus for the study of this new field.

René Descartes and Pierre Fermat both applied their newly discovered analytic geometry to the study of conics.

However, it was John Wallis in his 1655 treatise Tractatus de sectionibus conicis who first defined the conic sections as instances of equations of second degree.

[41] Written earlier, but published later, Jan de Witt's Elementa Curvarum Linearum starts with Kepler's kinematic construction of the conics and then develops the algebraic equations.

Some authors prefer to write the general homogeneous equation as (or some variation of this) so that the matrix of the conic section has the simpler form, but this notation is not used in this article.

As multiplying all six coefficients by the same non-zero scalar yields an equation with the same set of zeros, one can consider conics, represented by (A, B, C, D, E, F) as points in the five-dimensional projective space

A synthetic (coordinate-free) approach to defining the conic sections in a projective plane was given by Jakob Steiner in 1867.

A polarity, π, of a projective plane P is an involutory bijection between the points and the lines of P that preserves the incidence relation.

One of them is based on the converse of Pascal's theorem, namely, if the points of intersection of opposite sides of a hexagon are collinear, then the six vertices lie on a conic.

The empty set case may correspond either to a pair of complex conjugate parallel lines such as with the equation

[68] The solutions to a system of two second degree equations in two variables may be viewed as the coordinates of the points of intersection of two generic conic sections.

The classification into elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic is pervasive in mathematics, and often divides a field into sharply distinct subfields.