Infinitesimal

The word infinitesimal comes from a 17th-century Modern Latin coinage infinitesimus, which originally referred to the "infinity-eth" item in a sequence.

As calculus developed further, infinitesimals were replaced by limits, which can be calculated using the standard real numbers.

Vladimir Arnold wrote in 1990: Nowadays, when teaching analysis, it is not very popular to talk about infinitesimal quantities.

Hence, when used as an adjective in mathematics, infinitesimal means infinitely small, smaller than any standard real number.

Simon Stevin's work on the decimal representation of all numbers in the 16th century prepared the ground for the real continuum.

Bonaventura Cavalieri's method of indivisibles led to an extension of the results of the classical authors.

The use of infinitesimals by Leibniz relied upon heuristic principles, such as the law of continuity: what succeeds for the finite numbers succeeds also for the infinite numbers and vice versa; and the transcendental law of homogeneity that specifies procedures for replacing expressions involving unassignable quantities, by expressions involving only assignable ones.

As Cantor and Dedekind were developing more abstract versions of Stevin's continuum, Paul du Bois-Reymond wrote a series of papers on infinitesimal-enriched continua based on growth rates of functions.

A mathematical implementation of both the law of continuity and infinitesimals was achieved by Abraham Robinson in 1961, who developed nonstandard analysis based on earlier work by Edwin Hewitt in 1948 and Jerzy Łoś in 1955.

The English mathematician John Wallis introduced the expression 1/∞ in his 1655 book Treatise on the Conic Sections.

The concept suggests a thought experiment of adding an infinite number of parallelograms of infinitesimal width to form a finite area.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the calculus was reformulated by Augustin-Louis Cauchy, Bernard Bolzano, Karl Weierstrass, Cantor, Dedekind, and others using the (ε, δ)-definition of limit and set theory.

[8] The mathematical study of systems containing infinitesimals continued through the work of Levi-Civita, Giuseppe Veronese, Paul du Bois-Reymond, and others, throughout the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, as documented by Philip Ehrlich (2006).

In the 20th century, it was found that infinitesimals could serve as a basis for calculus and analysis (see hyperreal numbers).

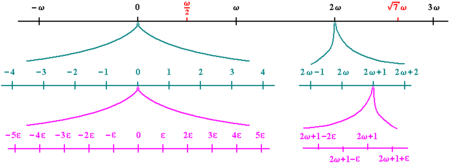

In extending the real numbers to include infinite and infinitesimal quantities, one typically wishes to be as conservative as possible by not changing any of their elementary properties.

We can distinguish three levels at which a non-Archimedean number system could have first-order properties compatible with those of the reals: Systems in category 1, at the weak end of the spectrum, are relatively easy to construct but do not allow a full treatment of classical analysis using infinitesimals in the spirit of Newton and Leibniz.

Increasing the analytic strength of the system by passing to categories 2 and 3, we find that the flavor of the treatment tends to become less constructive, and it becomes more difficult to say anything concrete about the hierarchical structure of infinities and infinitesimals.

This property of being able to carry over all relations in a natural way is known as the transfer principle, proved by Jerzy Łoś in 1955.

Synthetic differential geometry or smooth infinitesimal analysis have roots in category theory.

This approach departs from the classical logic used in conventional mathematics by denying the general applicability of the law of excluded middle – i.e., not (a ≠ b) does not have to mean a = b.

to write down a unit impulse, infinitely tall and narrow Dirac-type delta function

The article by Yamashita (2007) contains bibliography on modern Dirac delta functions in the context of an infinitesimal-enriched continuum provided by the hyperreals.

The method of constructing infinitesimals of the kind used in nonstandard analysis depends on the model and which collection of axioms are used.

The method may be considered relatively complex but it does prove that infinitesimals exist in the universe of ZFC set theory.

Calculus textbooks based on infinitesimals include the classic Calculus Made Easy by Silvanus P. Thompson (bearing the motto "What one fool can do another can"[15]) and the German text Mathematik fur Mittlere Technische Fachschulen der Maschinenindustrie by R.

[19] The authors introduce the language of first-order logic, and demonstrate the construction of a first order model of the hyperreal numbers.

The text provides an introduction to the basics of integral and differential calculus in one dimension, including sequences and series of functions.

In a related but somewhat different sense, which evolved from the original definition of "infinitesimal" as an infinitely small quantity, the term has also been used to refer to a function tending to zero.

More precisely, Loomis and Sternberg's Advanced Calculus defines the function class of infinitesimals,

,[21] coinciding with the traditional notation for the classical (though logically flawed) notion of a differential as an infinitely small "piece" of F. This definition represents a generalization of the usual definition of differentiability for vector-valued functions of (open subsets of) Euclidean spaces.