Conservation and restoration of ancient Greek pottery

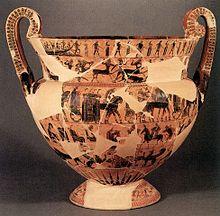

The information learned from vase paintings forms the foundation of modern knowledge of ancient Greek art and culture.

Professional conservator-restorers, often in collaboration with curators and conservation scientists, undertake the conservation-restoration of ancient Greek pottery.

[1] Archaeological discoveries and a surge in the popularity of ancient Greek art in the 18th and 19th centuries created a high demand for objects and artifacts.

[1] Materials used included shellac, protein glues, oil paints, gypsum, plaster of Paris, barium sulfate, calcite, clay, kaolin, and water glass (calcium silicate).

[3] In some cases, decorative imagery was censored and painted over, in order to appeal to the tastes of contemporary society and potential collectors.

Iron is the most common material found in clay, and can add red, grey, or buff coloring to the object.

Vase paintings were primarily created using slip, a thin, transparent layer of clay which turned color after firing.

Most agents of deterioration are due to environment and are inherent to the materials; however, the most common damage is caused by human action.

[7] If a piece of pottery has been buried in salty or alkaline soil or submersed in seawater, the clay may have soaked up soluble salts, such as sulphite, nitrates, or chlorides.

Cotton gloves are not recommended, because the fabric prevents a stable grip and threads can snag on rough surfaces.

Objects on display in museums are secured with mounts or protected by cases to prevent unwanted or accidental contact.

Conservators begin the evaluation of an object with careful visual inspection to identify areas of weakness, loss, delamination, discoloration, or old repairs.

Further examination with a low power microscope can help conservators identify materials and technical features, such as pigment, gilding, or added clay.

Conservators use identifying clues, such as shape, texture, and decorative pattern or painted scenes, to piece together fragments.

Some conservators leave replacement fragments completely undecorated in order to easily distinguish them as modern additions.

Some conservators paint silhouettes of missing figures, using existing fragments, scene narrative, and other extant vases as examples.

This approach helps show the narrative of the painted scene, while still distinguishing the modern restoration from the original fragments.

The Affecter Amphora, in the collection of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, Maryland, is a case study for the history of conservation of Greek vases.

Conservators also discovered that the vase was restored in the late 19th century with materials and methods typical of the time period.

In the year 1900, a member of the museum staff smashed the display case and the vase shattered into over 600 pieces.