Conspicuous consumption

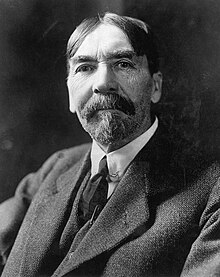

[1] In 1899, the sociologist Thorstein Veblen coined the term conspicuous consumption to explain the spending of money on and the acquiring of luxury commodities (goods and services) specifically as a public display of economic power—the income and the accumulated wealth—of the buyer.

The strength of one's reputation is in direct relationship to the amount of money possessed and displayed; that is to say, the basis "of gaining and retaining a good name, are leisure and conspicuous consumption.

"[7] In the 1920s, economists such as Paul Nystrom proposed that changes in lifestyle as result of the industrial age led to massive expansion of the "pecuniary emulation.

[9][10] Veblen said that conspicuous consumption comprised socio-economic behaviours practised by rich people as activities usual and exclusive to people with much disposable income;[8] yet a variation of Veblen's theory is presented in the conspicuous consumption behaviours that are very common to the middle class and to the working class, regardless of the person's race and ethnic group.

[12] Since the 19th century, conspicuous consumption explains the psychology behind the economics of a consumer society, and the increase in the types of goods and services that people consider necessary to and for their lives in a developed economy.

[21] Scholar Andrew Trigg (2001) defined conspicuous consumption as behaviour by which one can display great wealth, by means of idleness—expending much time in the practice of leisure activities, and spending much money to consume luxury goods and services.

station wagon/estate car), as a form of psychologically comforting conspicuous consumption, because such large vehicles usually are bought by city-dwellers, an urban nuclear family.

[25] Conspicuous consumption is exemplified by purchasing goods that are exclusively designed to serve as symbols of wealth, such as luxury-brand clothing, high-tech tools, and vehicles.

[31] During periods of economic downturn, consumers tend to turn away from "logomania" products and instead purchase luxury goods that signal affluence more subtly.

In 1919, the journalist H. L. Mencken addressed the sociological and psychological particulars of the socio-economic behaviours that are conspicuous consumption, by asking:Do I enjoy a decent bath because I know that John Smith cannot afford one—or because I delight in being clean?

That such socio-economic behaviours, facilitated by easy access to credit, generate macroeconomic volatility and support Veblen's concept of pecuniary emulation used to finance a person's social standing.

[51] In the case where inequality lowers savings, and increases leverage and a tendency to run large current account imbalances via the expenditure cascade mechanism, this has been associated with more frequent and/or severe economic crisis.

When individuals are concerned with their relative income or consumption in comparison to their peers, the optimal degree of public good provision and of progression of the tax system is raised.

[68]The economic case for the taxation of positional, luxury goods has a long history; in the mid-19th century, in Principles of Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy (1848), John Stuart Mill said: I disclaim all asceticism, and by no means wish to see discouraged, either by law or opinion, any indulgence which is sought from a genuine inclination for, any enjoyment of, the thing itself; but a great portion of the expenses of the higher and middle classes in most countries ... is not incurred for the sake of the pleasure afforded by the things on which the money is spent, but from regard to opinion, and an idea that certain expenses are expected from them, as an appendage of station; and I cannot but think that expenditure of this sort is a most desirable subject of taxation.

[69]In the case where conspicuous consumption mediates a link between inequality and unsustainable borrowing, one suggested policy response is tighter financial regulation.