Constellation

[2] Twelve (or thirteen) ancient constellations belong to the zodiac (straddling the ecliptic, which the Sun, Moon, and planets all traverse).

The origins of the zodiac remain historically uncertain; its astrological divisions became prominent c. 400 BC in Babylonian or Chaldean astronomy.

Some astronomical naming systems include the constellation where a given celestial object is found to convey its approximate location in the sky.

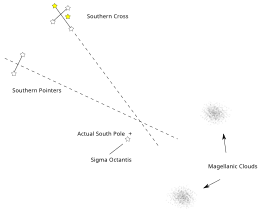

Other star patterns or groups called asterisms are not constellations under the formal definition, but are also used by observers to navigate the night sky.

[6][7] The word constellation comes from the Late Latin term cōnstellātiō, which can be translated as "set of stars"; it came into use in Middle English during the 14th century.

These terms historically referred to any recognisable pattern of stars whose appearance was associated with mythological characters or creatures, earthbound animals, or objects.

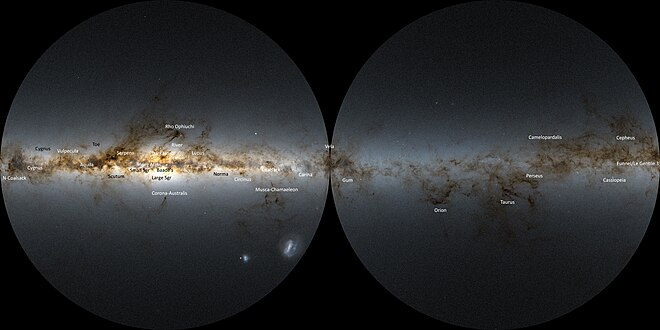

[17] The 88 constellations recognized by the IAU as well as those by cultures throughout history are imagined figures and shapes derived from the patterns of stars in the observable sky.

[21] Constellation positions change throughout the year due to night on Earth occurring at gradually different portions of its orbit around the Sun.

[26] Constellations near the pole star include Chamaeleon, Apus and Triangulum Australe (near Centaurus), Pavo, Hydrus, and Mensa.

[23] It has been suggested that the 17,000-year-old cave paintings in Lascaux, southern France, depict star constellations such as Taurus, Orion's Belt, and the Pleiades.

[27][28] Inscribed stones and clay writing tablets from Mesopotamia (in modern Iraq) dating to 3000 BC provide the earliest generally accepted evidence for humankind's identification of constellations.

[30] Biblical scholar E. W. Bullinger interpreted some of the creatures mentioned in the books of Ezekiel and Revelation as the middle signs of the four-quarters of the Zodiac,[32][33] with the Lion as Leo, the Bull as Taurus, the Man representing Aquarius, and the Eagle standing in for Scorpio.

[36] Greek astronomy essentially adopted the older Babylonian system in the Hellenistic era,[citation needed] first introduced to Greece by Eudoxus of Cnidus in the 4th century BC.

The basis of Western astronomy as taught during Late Antiquity and until the Early Modern period is the Almagest by Ptolemy, written in the 2nd century.

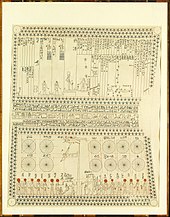

[37] Some of these were combined with Greek and Babylonian astronomical systems culminating in the Zodiac of Dendera; it remains unclear when this occurred, but most were placed during the Roman period between 2nd to 4th centuries AD.

[39] Nonspecific Chinese star names, later categorized in the twenty-eight mansions, have been found on oracle bones from Anyang, dating back to the middle Shang dynasty.

Parallels to the earliest Babylonian (Sumerian) star catalogues suggest that the ancient Chinese system did not arise independently.

Chen Zhuo's work has been lost, but information on his system of constellations survives in Tang period records, notably by Qutan Xida.

[41] A well-known map from the Song period is the Suzhou Astronomical Chart, which was prepared with carvings of stars on the planisphere of the Chinese sky on a stone plate; it is done accurately based on observations, and it shows the 1054 supernova in Taurus.

[41] Influenced by European astronomy during the late Ming dynasty, charts depicted more stars but retained the traditional constellations.

Before astronomers delineated precise boundaries (starting in the 19th century), constellations generally appeared as ill-defined regions of the sky.

[44] Today they now follow officially accepted designated lines of right ascension and declination based on those defined by Benjamin Gould in epoch 1875.0 in his star catalogue Uranometria Argentina.

The southern sky, below about −65° declination, was only partially catalogued by ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese, and Persian astronomers of the north.

Italian explorers who recorded new southern constellations include Andrea Corsali, Antonio Pigafetta, and Amerigo Vespucci.

[34] Many of the 88 IAU-recognized constellations in this region first appeared on celestial globes developed in the late 16th century by Petrus Plancius, based mainly on observations of the Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser[47] and Frederick de Houtman.

[52] Fourteen more were created in 1763 by the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille, who also split the ancient constellation Argo Navis into three; these new figures appeared in his star catalogue, published in 1756.

The northern constellation Quadrans Muralis survived into the 19th century (when its name was attached to the Quadrantid meteor shower), but is now divided between Boötes and Draco.

In 1928, the IAU formally accepted the 88 modern constellations, with contiguous boundaries[59] along vertical and horizontal lines of right ascension and declination developed by Eugene Delporte that, together, cover the entire celestial sphere;[5][60] this list was finally published in 1930.

The consequence of this early date is that because of the precession of the equinoxes, the borders on a modern star map, such as epoch J2000, are already somewhat skewed and no longer perfectly vertical or horizontal.