Su Song

[5][6][7] Su's clock tower also featured the oldest known endless power-transmitting chain drive, called the tian ti (天梯), or "celestial ladder", as depicted in his horological treatise.

[11] Although not as prominent as in the Song period, contemporary Chinese texts of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) described a relatively unbroken history of mechanical clocks in China, from the 13th to the 16th century.

It was thus not fully mechanical like late medieval European clocks, which typically used descending weights to drive their gears and escapement, requiring periodic winding but functioning without continuous external forces.

It was written by his junior colleague and Hanlin scholar Ye Mengde (1077–1148)[16] that in Su's youth, he mastered the provincial exams and rose to the top of the examination list for writing the best article on general principles and structure of the Chinese calendar.

"[24] In 1081, the court instructed Su Song to compile into a book the diplomatic history of Song-Liao relations, an elaborate task that, once complete, filled 200 volumes.

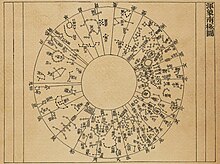

[26] Su Song also created a celestial atlas (in five separate maps), which had the hour circles between the xiu (lunar mansions) forming the astronomical meridians, with stars marked in an equidistant cylindrical projection on each side of the equator,[28] and thus, was in accordance to their north polar distances.

[31] In 1070, Su Song and a team of scholars compiled and edited the Bencao Tujing ('Illustrated Pharmacopoeia', original source material from 1058 to 1061), which was a groundbreaking treatise on pharmaceutical botany, zoology, and mineralogy.

[35] Su's book was also the first pharmaceutical treatise written in China to describe the flax, Urtica thunbergiana, and Corchoropsis tomentosa (crenata) plants.

[38] Su made systematic descriptions of animals and the environmental regions they could be found, such as different species of freshwater, marine, and shore crabs.

[39] For example, he noted that the freshwater crab species Eriocher sinensis could be found in the Huai River running through Anhui, in waterways near the capital city, as well as reservoirs and marshes of Hebei.

[40] Su Song compiled one of the greatest Chinese horological treatises of the Middle Ages, surrounding himself with an entourage of notable engineers and astronomers to assist in various projects.

"Essentials of a New Method for Mechanizing the Rotation of an Armillary Sphere and a Celestial Globe"), written in 1092, was the final product of his life's achievements in horology and clockwork.

[42][43] The emperor had previously commissioned Han Gonglian, Acting Secretary of the Ministry of Personnel, to head the project, but the leadership position was instead handed down to Su Song.

[45] In the end, the clock tower had many impressive features, such as the hydro-mechanical, rotating armillary sphere crowning the top level and weighing some 10 to 20 tons,[45] a bronze celestial globe located in the middle that was 4.5 feet in diameter,[45] mechanically timed and rotating mannequins dressed in miniature Chinese clothes that exited miniature opening doors to announce the time of day by presenting designated reading plaques, ringing bells and gongs, or beating drums,[46] a sophisticated use of oblique gears and an escapement mechanism,[47] as well as an exterior facade of a fanciful Chinese pagoda.

[12] The earliest such design of a sand-clock was made by Zhan Xiyuan around 1370, which featured not only the scoop wheel of Su Song' device, but also a new addition of a stationary dial face over which a pointer circulated, much like new European clocks of the same period.

[54] In Su Song's waterwheel linkwork device, the action of the escapement's arrest and release was achieved by gravity exerted periodically as the continuous flow of liquid filled containers of a limited size.

In his memorial, Su Song wrote about this concept: According to your servant's opinion there have been many systems and designs for astronomical instruments during past dynasties all differing from one another in minor respects.

Thus if the water is made to pour with perfect evenness, then the comparison of the rotary movements (of the heavens and the machine) will show no discrepancy or contradiction; for the unresting follows the unceasing.

[55]In his writing, Su Song credited, as the predecessor of his working clock, the hydraulic-powered armillary sphere of Zhang Heng (78–139 AD), an earlier Chinese scientist.

[57] The mechanical clockworks for Su Song's astronomical tower featured a great driving-wheel that was 11 feet in diameter, carrying 36 scoops, into each of which water poured at a uniform rate from the "constant-level tank" (Needham, Fig.

Its time-announcing function was further fulfilled visually and audibly by the performances of numerous jacks mounted on the eight superimposed wheels of a time-keeping shaft and appearing at windows in the pagoda-like structure at the front of the tower.

Within the building, some 40 ft. high, the driving-wheel was provided with a special form of escapement, and the water was pumped back into the tanks periodically by manual means.

[62]In addition, the motion gear rings and the upper drive wheel both had 600 teeth, which by Su's mathematical precision carefully calculated measured units of the day in a division of 1/600.

The chief difference was that Alfonso's instrument featured an arrangement for making measurements of the azimuth and altitude, which was present in the Arabic tradition, while Su Song's armillary sphere was duly graduated.

[68] The later Ming dynasty/Qing dynasty scholar Qian Zeng (1629–1699) held an old volume of Su's work, which he faithfully reproduced in a newly printed edition.

In 1956, John Christiansen reconstructed a model of Su Song's clocktower in a famous drawing, which garnered attention in the West towards 11th-century Chinese engineering.

[70] A miniature model of Su Song's clock was reconstructed by John Cambridge and is now on display at the National Science Museum at South Kensington, London.