Persian Constitutional Revolution

The revolutionaries – mainly bazaar merchants, the ulama, and a small group of radical reformers – argued that Iran's oil industry was being sold to the British, while tax breaks on imports, exports and manufactured textiles were destroying Iran's economy (which had been supported by the bazaar merchants), and that the shah was selling assets to pay interest on the fortune in foreign debt he had accumulated.

In the late 19th century, like most of the Muslim world, Iran suffered from foreign intrusion and exploitation, military weakness, lack of cohesion, and corruption.

A survey for the British Foreign Office reported: 'There are large tracts of fertile land which remain waste owing to their proximity to the main roads, as no village having cultivators on such spots can possibly prosper or enjoy the least immunity from the pestering visits of Government officials, and thefts and robberies committed by the tribes.

[20] Widows and orphans were hurt, and farmers suffered: by 1894 the price they were paid for wheat harvest dropped to 1/6 what it had been in 1871;[20] irrigation systems had fallen into ruin, "turning fields and villages into desert".

[21] In 1872, Nasir al-Din Shah negotiated a concession granting a British citizen control over Iranian roads, telegraphs, mills, factories, extraction of resources, and other public works in exchange for a fixed sum and 60% of net revenue.

[22] Other concessions to the British included giving the new Imperial Bank of Persia exclusive rights to issue banknotes, and opening up the Karun River to navigation.

In their writings these intellectuals criticized Iran's "autocratic rulers, petty officials, venal clerics, and arbitrary courts, and of the low status of women.

"[24] The "mercantile class" or bazaari became convinced that "law and order, security of property, and immunity from arbitrary power could all be achieved by importing parliamentary democracy" from Europe.

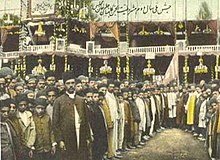

[25] The tobacco protest of 1891–1892 was "the first mass nationwide popular movement in Iran",[23] and described as a "dress rehearsal for the...Constitutional Revolution",[26] formed from an anti-imperialist and antimonarchist coalition of "clerics, mercantile interests, and dissident intellectuals".

At Mozaffar al-Din Shah's accession Iran faced a financial crisis, with annual governmental expenditures far in excess of revenues as a result of the policies of his father.

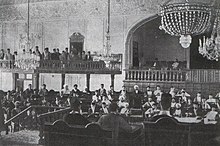

The shah yielded to the demonstrators on January 12, 1906, agreeing to dismiss his prime minister and transfer power to a "house of justice" (forerunner of the Iranian parliament).

[13] In 1908, the shah moved to "exploit the divisions within the ranks of the reformers" and eliminate the majlis,[13] staging a coup d'état and creating a period in Iranian history called the Minor Tyranny.

After shelling the Majles (parliament) of Iran in the capital Tehran, 40,000 of Mohammad Ali Shah's soldiers were ordered to attack Tabriz, where Constitutional rebels were holding out.

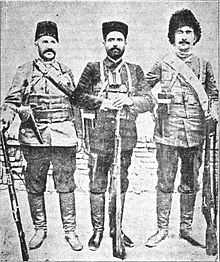

Inspired by this victory, constitutionalists across Iran set up special committees in Tehran, Rasht, Qazvin, Isfahan and other cities, and the powerful Bakhtiyari tribal leaders threw their support to the Tabriz rebels.

A further split in the revolutionary movement occurred in 1910 when "a group of guerrilla fighters headed by Sattar Khan, refused to obey a government order to disarm."

(Usuli Shi'i consider it obligatory for a Muslim not trained in the religious sciences to obey a mujtahid, i.e. a marja', when seeking to determine Islamically correct behavior.)

On the side of constitutional government were three of the highest level clerics (marja') at the time – Akhund Khurasani, Mirza Husayn Tehrani and Shaykh Abdullah Mazandarani – who telegraphed fatwa in favor of the constitution from their schools in Najaf, Iraq; of the three, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, (aka Akhund Khurasani) was the most involved in the issue, he and his student Muhammad Hossein Naini argued that while complete justice was impossible until the return of the Hidden Imam, "human experience and careful reflection" shows "that democracy reduces the tyranny of state" making it a "lesser evil" in governance and something Shi'i must support until the return of the Imam;[37] also supporting constitutionalism was Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi, who argued that only the sources of emulation (highest level clerics) should be heeded when it comes to matters of faith.

[42] In a letter dated June 3, 1907, the parliament told Akhund about a group of anti-constitutionalists who were trying to undermine legitimacy of democracy in the name of religious law.

Akhund Khurasani and the other two members of the trio (Mirza Husayn Tehrani and Shaykh Abdullah Mazandarani) replied: اساس این مجلس محترم مقدس بر امور مذکور مبتنی است.

[45] As a rich and high-ranking Qajar court official responsible for conducting marriages and contracts, handling the wills of wealthy men and collected religious funds,[46] Nouri had a powerful vested interest in maintaining the status quo of Iran's political structure.

[47] In his fight against the institution of parliament, he led a large group of followers and began a round-the-clock sit-in in the Shah Abdol-Azim Shrine on June 21, 1907 which lasted till September 16, 1907.

[48] In Zanjan, Mulla Qurban Ali Zanjani mobilized a force of six hundred thugs who looted shops of pro-democracy merchants, took hold of the city for several days, and killed the representative Sa'd al-Saltanih.

[51] Notified about Nouri's activities, Akhund Khurasani consulted the other Marja' and in a letter dated December 30, 1907, they issued a statement: چون نوری مخل آسائش و مفسد است، تصرفش در امور حرام است.

However, Nouri continued his activities and a few weeks later Akhund Khurasani and his fellow Marja's argued for his expulsion from Tehran: رفع اغتشاشات حادثه و تبعید نوری را عاجلاً اعلام.

He argued Islam contained a complete code of life, whereas democracy would allow for "teaching of chemistry, physics and foreign languages", which would cause the spread of atheism.

[59] He believed that the ruler was accountable to no institution other than God and people had no right to limit the powers or question the conduct of the shah; those who supported democratic form of government were corrupt and apostates from Islam.

They acted as a legitimising force,[62] invoking the Quranic command of 'enjoining good and forbidding wrong' to justify democracy in the period of occultation, and linked opposition to the constitutional movement to 'a war against the Imam of the Age',[63] (essential the worst condemnation possible in Shi'i Islam).

[64] Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi, the Thiqa tul-islam from Tabriz, opposed Nuri saying that only the opinion of the sources of emulation is worthy of consideration in the matters of faith.

[71] While Akhund Khorasani was an eminent Marja' in Najaf, many imitators (followers) prayed behind Kazem Yazdi too, as his lessons on legal rulings (fiqh) were famous.

[77] Ayatullah Yazdi said that as long as modern constitution did not force people to do what was forbidden by Sharia and refrain from religious duties, there was no reason to oppose democratic rule and the government had the right to prosecute wrongdoers.