Conte di Cavour-class battleship

In December 1915, and January 1916, when the Serbian army was driven by the German foces under General von Mackensen toward the Albanian coast, 138,000 Serbian infantry and 11,000 refugees were ferried across the Adriatic and landed in Italy in 87 trips by the Conte di Cavour and other shps of the Italian Navy under the command of Admiral Conz.

The two surviving ships, Conte di Cavour and Giulio Cesare, supported operations during the Corfu Incident in 1923.

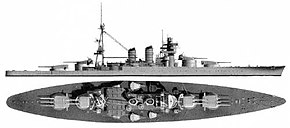

The Conte di Cavour–class ships were designed by Rear Admiral Engineer Edoardo Masdea, Chief Constructor of the Regia Marina, and were ordered in response to French plans to build the Courbet-class battleships.

As upgrading a warship's protection and armament on a similar displacement typically requires a loss in speed, the ships were not designed to reach the 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) of their predecessor.

The Conte di Cavour class was provided with a complete double bottom and their hulls were subdivided by 23 longitudinal and transverse bulkheads.

The ships could store a maximum of 1,450 long tons (1,470 t) of coal and 850 long tons (860 t) of fuel oil[8] that gave them a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), and 1,000 nautical miles (1,900 km; 1,200 mi) at 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph).

Sources disagree regarding these guns' performance, but naval historian Giorgio Giorgerini claims that they fired 452-kilogram (996 lb) armor-piercing (AP) projectiles at the rate of one round per minute and that they had a muzzle velocity of 840 m/s (2,800 ft/s) which gave a maximum range of 24,000 meters (26,000 yd).

[14] The secondary armament on the first two ships consisted of eighteen 50-caliber 120-millimeter (4.7 in) guns,[15] also designed by Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers,[16] mounted in casemates on the sides of the hull.

In 1925–1926 the foremast was replaced by a tetrapodal mast, which was moved forward of the funnels,[22] the rangefinders were upgraded, and the ships were equipped to handle a Macchi M.18 seaplane mounted on the center turret.

[Note 2] The sisters began an extensive reconstruction program directed by Vice Admiral (Generale del Genio navale) Francesco Rotundi in October 1933.

On her sea trials in December 1936, before her reconstruction was fully completed, Giulio Cesare reached a speed of 28.24 knots (52.30 km/h; 32.50 mph) from 93,430 shp (69,670 kW).

The ships now carried 2,550–2,605 long tons (2,591–2,647 t) of fuel oil which provided them with a range of 6,400 nautical miles (11,900 km; 7,400 mi) at a speed of 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph).

[31] The 320 mm AP shells weighed 525 kilograms (1,157 lb) and had a maximum range of 28,600 meters (31,300 yd) with a muzzle velocity of 830 m/s (2,700 ft/s).

[23] The existing underwater protection was replaced by the Pugliese system that consisted of a large cylinder surrounded by fuel oil or water that was intended to absorb the blast of a torpedo warhead.

A major problem of the reconstruction was that the ships' increased draft meant that their waterline armor belt was almost completely submerged with any significant load.

[22] Leonardo da Vinci was also little used and was sunk by an internal magazine explosion at Taranto harbor on the night of 2/3 August 1916 while loading ammunition.

[23] The Regia Marina planned to modernize her by replacing her center turret with six 102-millimeter (4 in) AA guns,[7] but lacked the funds to do so and sold her for scrap on 22 March 1923.

[35] In 1919, Conte di Cavour sailed to North America and visited ports in the United States as well as Halifax, Canada.

[42] Conte di Cavour escorted King Victor Emmanuel III and his wife aboard Dante Alighieri, on a state visit to Spain in 1924 and was placed in reserve upon her return until 1926, when she conveyed Mussolini on a voyage to Libya.

Conte di Cavour was reconstructed at the CRDA Trieste Yard while Giulio Cesare was rebuilt at Cantieri del Tirreno, Genoa between 1933 and 1937.

Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, attempted to interpose his ships between the Italians and their base at Taranto.

Crew on the fleets spotted each other in the middle of the afternoon and the Italian battleships opened fire at 15:53 at a range of nearly 27,000 meters (29,000 yd).

Three minutes after she opened fire, shells from Giulio Cesare began to straddle Warspite which made a small turn and increased speed, to throw off the Italian ship's aim, at 16:00.

Uncertain how severe the damage was, Campioni ordered his battleships to turn away in the face of superior British numbers and they successfully disengaged.

[44] On the night of 11 November 1940, Conte di Cavour and Giulio Cesare were at anchor in Taranto harbor when they were attacked by 21 Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers from the British aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, along with several other warships.

One torpedo exploded underneath 'B' turret at 23:15, and her captain requested tugboats to help ground the ship on a nearby 12-meter (39 ft) sandbank.

In an effort to lighten the ship, her guns and parts of her superstructure were removed and Conte di Cavour was refloated on 9 June 1941.

Her guns were operable by September 1942, but replacing her entire electrical system took longer and she was still under repair when Italy surrendered a year later.

She participated in the First Battle of Sirte on 17 December 1941, providing distant cover for a convoy bound for Libya, again never firing her main armament.

While at anchor in Sevastopol on the night of 28/29 October 1955, she detonated a large German mine left over from World War II.