Convection

Heat transfer by natural convection plays a role in the structure of Earth's atmosphere, its oceans, and its mantle.

In treatise VIII by William Prout, in the book on chemistry, it says:[1] [...] This motion of heat takes place in three ways, which a common fire-place very well illustrates.

If, for instance, we place a thermometer directly before a fire, it soon begins to rise, indicating an increase of temperature.

In this case the heat has made its way through the space between the fire and the thermometer, by the process termed radiation.

Later, in the same treatise VIII, in the book on meteorology, the concept of convection is also applied to "the process by which heat is communicated through water".

The pressure at the bottom of a submerged object then exceeds that at the top, resulting in a net upward buoyancy force equal to the weight of the displaced fluid.

In nature, convection cells formed from air raising above sunlight-warmed land or water are a major feature of all weather systems.

In engineering applications, convection is commonly visualized in the formation of microstructures during the cooling of molten metals, and fluid flows around shrouded heat-dissipation fins, and solar ponds.

[5] For example, gravitational convection can be seen in the diffusion of a source of dry salt downward into wet soil due to the buoyancy of fresh water in saline.

[6] Variable salinity in water and variable water content in air masses are frequent causes of convection in the oceans and atmosphere which do not involve heat, or else involve additional compositional density factors other than the density changes from thermal expansion (see thermohaline circulation).

In the presence of a temperature gradient this results in a nonuniform magnetic body force, which leads to fluid movement.

In a zero-gravity environment, there can be no buoyancy forces, and thus no convection possible, so flames in many circumstances without gravity smother in their own waste gases.

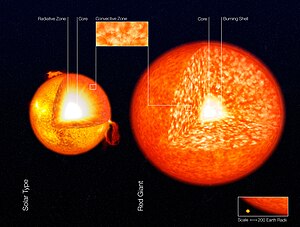

On astronomical scales, convection of gas and dust is thought to occur in the accretion disks of black holes, at speeds which may closely approach that of light.

[8][9] Another common experiment to demonstrate thermal convection in liquids involves submerging open containers of hot and cold liquid coloured with dye into a large container of the same liquid without dye at an intermediate temperature (for example, a jar of hot tap water coloured red, a jar of water chilled in a fridge coloured blue, lowered into a clear tank of water at room temperature).

When the card is removed, if the jar containing the warmer liquid is placed on top no convection will occur.

If the jar containing colder liquid is placed on top, a convection current will form spontaneously.

Additionally, convection cells can arise due to density variations resulting from differences in the composition of electrolytes.

Latitudinal circulation occurs because incident solar radiation per unit area is highest at the heat equator, and decreases as the latitude increases, reaching minima at the poles.

Some more localized phenomena than global atmospheric movement are also due to convection, including wind and some of the hydrologic cycle.

If enough instability is present in the atmosphere, this process will continue long enough for cumulonimbus clouds to form, which support lightning and thunder.

Generally, thunderstorms require three conditions to form: moisture, an unstable airmass, and a lifting force (heat).

At the consumption edges of the plate, the material has thermally contracted to become dense, and it sinks under its own weight in the process of subduction at an ocean trench.

As the flow develops and the water cools further, the decrease in density causes a recirculation current at the bottom right corner of the cavity.

This causes the water at that wall to become supercooled, create a counter-clockwise flow, and initially overpower the warm current.

In this way, natural circulation will ensure that the fluid will continue to flow as long as the reactor is hotter than the heat sink, even when power cannot be supplied to the pumps.

Notable examples are the S5G [43][44][45] and S8G[46][47][48] United States Naval reactors, which were designed to operate at a significant fraction of full power under natural circulation, quieting those propulsion plants.

Then: Natural convection is highly dependent on the geometry of the hot surface, various correlations exist in order to determine the heat transfer coefficient.

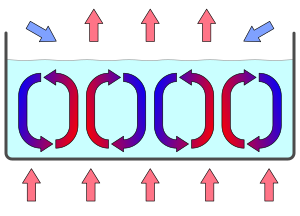

When heat is fed into the system from one direction (usually below), at small values it merely diffuses (conducts) from below upward, without causing fluid flow.

This breaks the symmetry of the system, and generally changes the pattern of up- and down-moving fluid from stripes to hexagons, as seen at right.

As the Rayleigh number is increased even further above the value where convection cells first appear, the system may undergo other bifurcations, and other more complex patterns, such as spirals, may begin to appear.