Convective available potential energy

In meteorology, convective available potential energy (commonly abbreviated as CAPE),[1] is a measure of the capacity of the atmosphere to support upward air movement that can lead to cloud formation and storms.

Some atmospheric conditions, such as very warm, moist, air in an atmosphere that cools rapidly with height, can promote strong and sustained upward air movement, possibly stimulating the formation of cumulus clouds or cumulonimbus (thunderstorm clouds).

By contrast, other conditions, such as a less warm air parcel or a parcel in an atmosphere with a temperature inversion (in which the temperature increases above a certain height) have much less capacity to support vigorous upward air movement, thus the potential energy level (CAPE) would be much lower, as would the probability of thunderstorms.

Any value greater than 0 J/kg indicates instability and an increasing possibility of thunderstorms and hail.

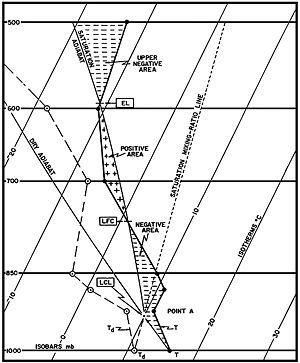

On a sounding diagram, CAPE is the positive area above the LFC, the area between the parcel's virtual temperature line and the environmental virtual temperature line where the ascending parcel is warmer than the environment.

When a parcel is unstable, it will continue to move vertically, in either direction, dependent on whether it receives upward or downward forcing, until it reaches a stable layer (though momentum, gravity, and other forcing may cause the parcel to continue).

[3] Fluid elements displaced upwards or downwards in such an atmosphere expand or compress adiabatically in order to remain in pressure equilibrium with their surroundings, and in this manner become less or more dense.

If the adiabatic decrease or increase in density is less than the decrease or increase in the density of the ambient (not moved) medium, then the displaced fluid element will be subject to downwards or upwards pressure, which will function to restore it to its original position.

Deep, moist convection requires a parcel to be lifted to the LFC where it then rises spontaneously until reaching a layer of non-positive buoyancy.

The atmosphere is warm at the surface and lower levels of the troposphere where there is mixing (the planetary boundary layer (PBL)), but becomes substantially cooler with height.

When the rising air parcel cools more slowly than the surrounding atmosphere, it remains warmer and less dense.

The parcel continues to rise freely (convectively; without mechanical lift) through the atmosphere until it reaches an area of air less dense (warmer) than itself.

The amount, and shape, of the positive-buoyancy area modulates the speed of updrafts, thus extreme CAPE can result in explosive thunderstorm development; such rapid development usually occurs when CAPE stored by a capping inversion is released when the "lid" is broken by heating or mechanical lift.

The amount of CAPE also modulates how low-level vorticity is entrained and then stretched in the updraft, with importance to tornadogenesis.

On these days, it was apparent that conditions were ripe for tornadoes and CAPE wasn't a crucial factor.

However, extreme CAPE, by modulating the updraft (and downdraft), can allow for exceptional events, such as the deadly F5 tornadoes that hit Plainfield, Illinois on August 28, 1990, and Jarrell, Texas on May 27, 1997, on days which weren't readily apparent as conducive to large tornadoes.

The surprise severe weather event that occurred in Illinois and Indiana on April 20, 2004, is a good example.

Owing to thermodynamic processes, as the dry mid-level air is slowly saturated its temperature begins to drop, increasing the adiabatic lapse rate.

Under certain conditions, the lapse rate can increase significantly in a short amount of time, resulting in convection.

High convective instability can lead to severe thunderstorms and tornadoes as moist air which is trapped in the boundary layer eventually becomes highly negatively buoyant relative to the adiabatic lapse rate and escapes as a rapidly rising bubble of humid air triggering the development of a cumulus or cumulonimbus cloud.

To make the process more realistic for tropical cyclones is to use Reversible CAPE (RCAPE for short).

RCAPE assumes the opposite extreme to the standard convention of CAPE and is that no liquid water will be lost during the process.