Convergent evolution

Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last common ancestor of those groups.

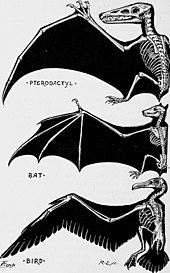

Bird, bat, and pterosaur wings are analogous structures, but their forelimbs are homologous, sharing an ancestral state despite serving different functions.

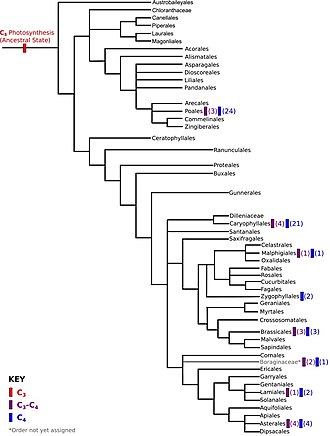

Many instances of convergent evolution are known in plants, including the repeated development of C4 photosynthesis, seed dispersal by fleshy fruits adapted to be eaten by animals, and carnivory.

[4] In biochemistry, physical and chemical constraints on mechanisms have caused some active site arrangements such as the catalytic triad to evolve independently in separate enzyme superfamilies.

"[6] Simon Conway Morris disputes this conclusion, arguing that convergence is a dominant force in evolution, and given that the same environmental and physical constraints are at work, life will inevitably evolve toward an "optimum" body plan, and at some point, evolution is bound to stumble upon intelligence, a trait presently identified with at least primates, corvids, and cetaceans.

Homoplastic traits caused by convergence are therefore, from the point of view of cladistics, confounding factors which could lead to an incorrect analysis.

From a mathematical standpoint, an unused gene (selectively neutral) has a steadily decreasing probability of retaining potential functionality over time.

The time scale of this process varies greatly in different phylogenies; in mammals and birds, there is a reasonable probability of remaining in the genome in a potentially functional state for around 6 million years.

[17][18] When the ancestral forms are unspecified or unknown, or the range of traits considered is not clearly specified, the distinction between parallel and convergent evolution becomes more subjective.

For instance, the striking example of similar placental and marsupial forms is described by Richard Dawkins in The Blind Watchmaker as a case of convergent evolution, because mammals on each continent had a long evolutionary history prior to the extinction of the dinosaurs under which to accumulate relevant differences.

These examples reflect the intrinsic chemical constraints on enzymes, leading evolution to converge on equivalent solutions independently and repeatedly.

[25] Distant homologues of the metal ion transporters ZIP in land plants and chlorophytes have converged in structure, likely to take up Fe2+ efficiently.

The IRT1 proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana and rice have extremely different amino acid sequences from Chlamydomonas's IRT1, but their three-dimensional structures are similar, suggesting convergent evolution.

One well-characterized example is the evolution of resistance to cardiotonic steroids (CTSs) via amino acid substitutions at well-defined positions of the α-subunit of Na+,K+-ATPase (ATPalpha).

[27][29] Convergence occurs at the level of DNA and the amino acid sequences produced by translating structural genes into proteins.

Studies have found convergence in amino acid sequences in echolocating bats and the dolphin;[30] among marine mammals;[31] between giant and red pandas;[32] and between the thylacine and canids.

[34][35] Swimming animals including fish such as herrings, marine mammals such as dolphins, and ichthyosaurs (of the Mesozoic) all converged on the same streamlined shape.

[40] The marsupial fauna of Australia and the placental mammals of the Old World have several strikingly similar forms, developed in two clades, isolated from each other.

Around 20 million years after acquiring that ability, both groups evolved active electrogenesis, producing weak electric fields to help them detect prey.

[43] One of the best-known examples of convergent evolution is the camera eye of cephalopods (such as squid and octopus), vertebrates (including mammals) and cnidarians (such as jellyfish).

[45] Their last common ancestor had at most a simple photoreceptive spot, but a range of processes led to the progressive refinement of camera eyes—with one sharp difference: the cephalopod eye is "wired" in the opposite direction, with blood and nerve vessels entering from the back of the retina, rather than the front as in vertebrates.

[46] Birds and bats have homologous limbs because they are both ultimately derived from terrestrial tetrapods, but their flight mechanisms are only analogous, so their wings are examples of functional convergence.

Convergent evolution of many groups of insects led from original biting-chewing mouthparts to different, more specialised, derived function types.

[56] It appears certain that there was some lightening of skin colour before European and East Asian lineages diverged, as there are some skin-lightening genetic differences that are common to both groups.

[69] This implies convergent evolution under selective pressure, in this case the competition for seed dispersal by animals through consumption of fleshy fruits.