Convex set

[1][2] For example, a solid cube is a convex set, but anything that is hollow or has an indent, for example, a crescent shape, is not convex.

The notion of a convex set in Euclidean spaces can be generalized in several ways by modifying its definition, for instance by restricting the line segments that such a set is required to contain.

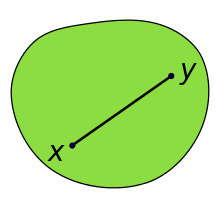

A subset C of S is convex if, for all x and y in C, the line segment connecting x and y is included in C. This means that the affine combination (1 − t)x + ty belongs to C for all x,y in C and t in the interval [0, 1].

This implies that convexity is invariant under affine transformations.

Further, it implies that a convex set in a real or complex topological vector space is path-connected (and therefore also connected).

A set C is strictly convex if every point on the line segment connecting x and y other than the endpoints is inside the topological interior of C. A closed convex subset is strictly convex if and only if every one of its boundary points is an extreme point.

The convex subsets of R (the set of real numbers) are the intervals and the points of R. Some examples of convex subsets of the Euclidean plane are solid regular polygons, solid triangles, and intersections of solid triangles.

The Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra are examples of non-convex sets.

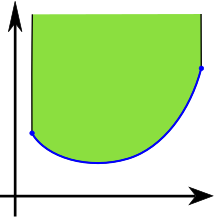

[6][7] The complement of a convex set, such as the epigraph of a concave function, is sometimes called a reverse convex set, especially in the context of mathematical optimization.

The collection of convex subsets of a vector space, an affine space, or a Euclidean space has the following properties:[9][10] Closed convex sets are convex sets that contain all their limit points.

They can be characterised as the intersections of closed half-spaces (sets of points in space that lie on and to one side of a hyperplane).

From what has just been said, it is clear that such intersections are convex, and they will also be closed sets.

To prove the converse, i.e., every closed convex set may be represented as such intersection, one needs the supporting hyperplane theorem in the form that for a given closed convex set C and point P outside it, there is a closed half-space H that contains C and not P. The supporting hyperplane theorem is a special case of the Hahn–Banach theorem of functional analysis.

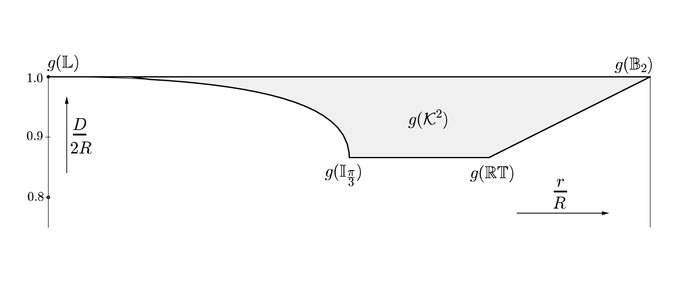

We can inscribe a rectangle r in C such that a homothetic copy R of r is circumscribed about C. The positive homothety ratio is at most 2 and:[13]

and can be visualized as the image of the function g that maps a convex body to the R2 point given by (r/R, D/2R).

can also be parametrized by its width (the smallest distance between any two different parallel support hyperplanes), perimeter and area.

In a real vector-space, the Minkowski sum of two (non-empty) sets, S1 and S2, is defined to be the set S1 + S2 formed by the addition of vectors element-wise from the summand-sets

More generally, the Minkowski sum of a finite family of (non-empty) sets Sn is the set formed by element-wise addition of vectors

in algebraic terminology, {0} is the identity element of Minkowski addition (on the collection of non-empty sets).

[16] Minkowski addition behaves well with respect to the operation of taking convex hulls, as shown by the following proposition: Let S1, S2 be subsets of a real vector-space, the convex hull of their Minkowski sum is the Minkowski sum of their convex hulls

This result holds more generally for each finite collection of non-empty sets:

[19] The following famous theorem, proved by Dieudonné in 1966, gives a sufficient condition for the difference of two closed convex subsets to be closed.

[20] It uses the concept of a recession cone of a non-empty convex subset S, defined as:

The notion of convexity in the Euclidean space may be generalized by modifying the definition in some or other aspects.

Let C be a set in a real or complex vector space.

[21] A set S in the Euclidean space is called orthogonally convex or ortho-convex, if any segment parallel to any of the coordinate axes connecting two points of S lies totally within S. It is easy to prove that an intersection of any collection of orthoconvex sets is orthoconvex.

The definition of a convex set and a convex hull extends naturally to geometries which are not Euclidean by defining a geodesically convex set to be one that contains the geodesics joining any two points in the set.

The subspace Y is a convex set if for each pair of points a, b in Y such that a ≤ b, the interval [a, b] = {x ∈ X | a ≤ x ≤ b} is contained in Y.

Given a set X, a convexity over X is a collection 𝒞 of subsets of X satisfying the following axioms:[9][10][23] The elements of 𝒞 are called convex sets and the pair (X, 𝒞) is called a convexity space.

For the ordinary convexity, the first two axioms hold, and the third one is trivial.

![Three squares are shown in the nonnegative quadrant of the Cartesian plane. The square Q1 = [0, 1] × [0, 1] is green. The square Q2 = [1, 2] × [1, 2] is brown, and it sits inside the turquoise square Q1+Q2=[1,3]×[1,3].](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Minkowski_sum_graph_-_vector_version.svg/220px-Minkowski_sum_graph_-_vector_version.svg.png)