Penal transportation

With modifications to the traditional benefit of clergy, which originally exempted only clergymen from the general criminal law, it developed into a legal fiction by which many common offenders of "clergyable" offences were extended the privilege to avoid execution.

Convicts were chosen carefully: the Acts of the Privy Council showed that prisoners "for strength of bodie or other abilities shall be thought fit to be employed in foreign discoveries or other services beyond the Seas".

[15] During the Commonwealth, Oliver Cromwell overcame the popular prejudice against subjecting Christians to slavery or selling them into foreign parts, and initiated group transportation of military[16] and civilian prisoners.

Alternatively, under the second act dealing with Moss-trooper brigands on the Scottish border, offenders had their benefit of clergy taken away, or otherwise at the judge's discretion, were to be transported to America, "there to remaine and not to returne".

[18][19] There were various influential agents of change: judges' discretionary powers influenced the law significantly, but the king's and Privy Council's opinions were decisive in granting a royal pardon from execution.

The reading test, crucial for the benefit of clergy, was a fundamental feature of the penal system, but to prevent its abuse, this pardoning process was used more strictly.

It was arranged that they fail the reading test, but they were then reprieved and held in jail, without bail, to allow time for a royal pardon (subject to transportation) to be organised.

Nevertheless, it could be argued that transportation was economically deleterious because the aim was to enlarge population, not diminish it;[24] but the character of an individual convict was likely to harm the economy.

[33] The Act led to significant changes: both petty and grand larceny were punished by transportation (seven years), and the sentence for any non-capital offence was at the judge's discretion.

With the exception of those years, the Transportation Act led to a decrease in whipping of convicts, thus avoiding potentially inflammatory public displays.

[43] The facts and numbers revealed how transportation was less frequently applied to women and children because they were usually guilty of minor crimes and they were considered a minimal threat to the community.

Parliament claimed that "the transportation of convicts to his Majesty's colonies and plantations in America ... is found to be attended with various inconveniences, particularly by depriving this kingdom of many subjects whose labour might be useful to the community, and who, by proper care and correction, might be reclaimed from their evil course"; they then passed the Criminal Law Act 1776 (16 Geo.

[51] In 1787, when transportation resumed to the chosen Australian colonies, the far greater distance added to the terrible experience of exile, and it was considered more severe than the methods of imprisonment employed for the previous decade.

The act also gave "authority to remit or shorten the time or term" of the sentence "in cases where it shall appear that such felons, or other offenders, are proper objects of the royal mercy"[53]

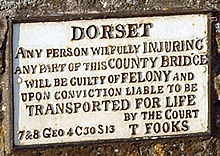

[52] With complaints starting in the 1830s, sentences of transportation became less common in 1840 since the system was perceived to be a failure: crime continued at high levels, people were not dissuaded from committing felonies, and the conditions of convicts in the colonies were inhumane.

Although a concerted programme of prison building ensued, the Short Titles Act 1896 lists seven other laws relating to penal transportation in the first half of the 19th century.

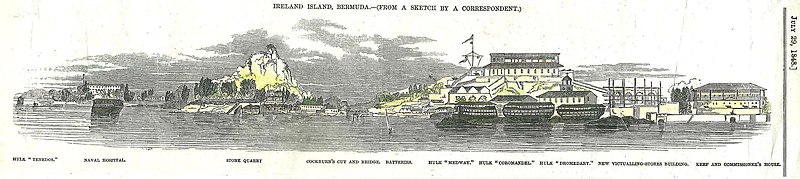

After the termination of transportation to North America, British prisons became overcrowded, and dilapidated ships moored in various ports were pressed into service as floating gaols known as "hulks".

[63] Following an 18th-century experiment in transporting convicted prisoners to Cape Coast Castle (modern Ghana) and the Gorée (Senegal) in West Africa,[64] British authorities turned their attention to New South Wales (in what would become Australia).

[66][67] In the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars, a group of Irish convicts joined the Aboriginal coalition of Eora, Gandangara, Dharug and Tharawal nations in their fight against the colonists.

In 1803, Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania) was also settled as a penal colony, followed by the Moreton Bay Settlement (modern Brisbane, Queensland) in 1824.

However, the Swan River Colony (Western Australia) accepted transportation from England and Ireland in 1851, to resolve a long-standing labour shortage.

[70] In 2013, an estimated 30% of the Australian population (about 7 million) had Irish ancestry – the highest percentage outside of Ireland – thanks partially to historical convict transportation.

[71] In British India – including the province of Burma (now Myanmar) and the port of Karachi (now part of Pakistan) – Indian independence activists were penally transported to the Andaman Islands.

[citation needed] The Cellular Jail in Port Blair, South Andaman Island, also called Kālā Pānī or Kalapani (Hindi for black waters), was constructed between 1896 and 1906 as a high-security prison with 698 individual cells for solitary confinement.

The most significant individual transported prisoner is probably French army officer Alfred Dreyfus, wrongly convicted of treason in a trial in 1894, held in an atmosphere of antisemitism.

The transportations had a twofold objective: to remove potential liabilities from the warfront, and to provide human capital for the settlement and industrialization of the largely underpopulated eastern regions.

The policy continued until February 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev in his speech, "On the Personality Cult and Its Consequences", condemned the transportation as a violation of Leninist principles.

Convicts and guards interact as they rehearse a theatre production, which the governor had suggested as an alternate form of entertainment instead of watching public hangings.

My Transportation for Life, Indian freedom fighter Veer Savarkar's memoir of his imprisonment, is set in the British Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands.

A classic example is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein (1966), in which convicts and political dissidents are transported to lunar colonies in order to grow food for Earth.