Copernican Revolution

[1] Beginning with the 1543 publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, contributions to the “revolution” continued until finally ending with Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

The "Copernican Revolution" is named for Nicolaus Copernicus, whose Commentariolus, written before 1514, was the first explicit presentation of the heliocentric model in Renaissance scholarship.

Martianus Capella (5th century CE) expressed the opinion that the planets Venus and Mercury did not go about the Earth but instead circled the Sun.

[2] Capella's model was discussed in the Early Middle Ages by various anonymous 9th-century commentators[3] and Copernicus mentions him as an influence on his own work.

[a] Otto E. Neugebauer in 1957 argued that the debate in 15th-century Latin scholarship must also have been informed by the criticism of Ptolemy produced after Averroes, by the Ilkhanid-era (13th to 14th centuries) Persian school of astronomy associated with the Maragheh observatory (especially the works of Al-Urdi, Al-Tusi and Ibn al-Shatir).

He is known to have studied the Epitome in Almagestum Ptolemei by Peuerbach and Regiomontanus (printed in Venice in 1496) and to have performed observations of lunar motions on 9 March 1497.

Copernicus went on to develop an explicitly heliocentric model of planetary motion, at first written in his short work Commentariolus some time before 1514, circulated in a limited number of copies among his acquaintances.

He continued to refine his system until publishing his larger work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543), which contained detailed diagrams and tables.

[10] In his article about heliocentrism as a model, author Owen Gingerich writes that in order to persuade people of the accuracy of his model, Copernicus created a mechanism in order to return the description of celestial motion to a “pure combination of circles.”[11] Copernicus’s theories made a lot of people uncomfortable and somewhat upset.

Even with the scrutiny that he faced regarding his conjecture that the universe was not centered around the Earth, he continued to gain support- other scientists and astrologists even posited that his system allowed a better understanding of astronomy concepts than did the geocentric theory.

Further advancement in the understanding of the cosmos would require new, more accurate observations than those that Nicolaus Copernicus relied on and Tycho made great strides in this area.

For eighteen months, it shone brightly in the sky with no visible parallax, indicating it was part of the heavenly region of stars according to Aristotle's model.

Galileo Galilei came after Kepler and developed his own telescope with enough magnification to allow him to study Venus and discover that it has phases like a moon.

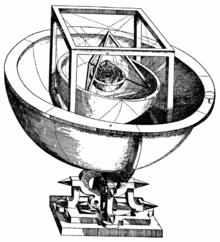

[15] In 1596, Kepler published his first book, the Mysterium Cosmographicum, which was the second (after Thomas Digges, in 1576) to endorse Copernican cosmology by an astronomer since 1540.

[12] The book described his model that used Pythagorean mathematics and the five Platonic solids to explain the number of planets, their proportions, and their order.

[19] This was a radical discovery because, according to Aristotelian cosmology, all heavenly bodies revolve around the Earth and a planet with moons obviously contradicted that popular belief.

[14] In the sixteenth century, a number of writers inspired by Copernicus, such as Thomas Digges,[22] Giordano Bruno[23] and William Gilbert[24] argued for an indefinitely extended or even infinite universe, with other stars as distant suns.

Although opposed by Copernicus and (initially) Kepler, in 1610 Galileo made his telescopic observation of the faint strip of the Milky Way, which he found it resolves in innumerable white star-like spots, presumably farther stars themselves.

Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason (1787 edition) drew a parallel between the "Copernican revolution" and the epistemology of his new transcendental philosophy.

For simplicity, Mars' period of revolution is depicted as 2 years instead of 1.88, and orbits are depicted as perfectly circular or epitrochoid .