Coptic architecture

Some authorities trace the origins of Coptic architecture to Ancient Egyptian architecture, seeing a similarity between the plan of ancient Egyptian temples, progressing from an outer courtyard to a hidden inner sanctuary to that of Coptic churches, with an outer narthex or porch, and (in later buildings) a sanctuary hidden behind an iconostasis.

The ruins of the cathedral at Hermopolis Magna (c.430–40) are the major survival of the single brief period when the Coptic Orthodox Church represented the official religion of the state in Egypt.

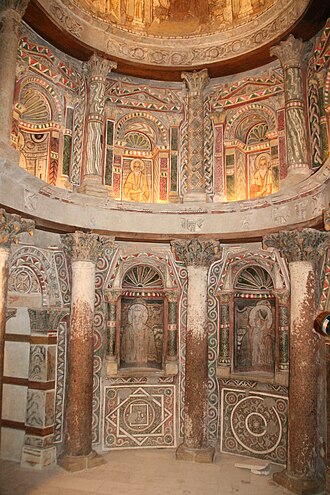

Thus, from its early beginnings Coptic architecture fused indigenous Egyptian building traditions and materials with Graeco-Roman and Christian Byzantine styles.

The fertile styles of neighbouring Christian Syria had a greatly increased influence after the 6th century, including the use of stone tympani.

[2] Over a period of two thousand years, Coptic architecture incorporated native Egyptian, Graeco-Roman, Byzantine and Western European styles.

Well before the break of 451, Egyptian Christianity had pioneered monasticism, with many communities being established in deliberately remote positions, especially in Southern Egypt.

Many Coptic monasteries and churches scattered throughout Egypt are built of mudbrick on the basilica plan inherited from Graeco-Roman architectural styles.

They usually have heavy walls and columns, architraves and barrel-vaulted roofs, and end in a tripartite apse, but many variant plans exist.

The iconostasis of Saint Mary Church in Harat Zewila in Old Cairo, rebuilt after 1321, shows the mixture of stylistic elements in Coptic architecture.

The older woodwork is Islamic in style, as are the Muqarnas in the pendentives, and a Gothic revival rood cross surmounts the iconostasis.

Early Coptic buildings contain elaborate and vigorous decorative carving on the capitals of columns, or friezes, some of which include interlace, confronted animals, and other motifs.