Corliss steam engine

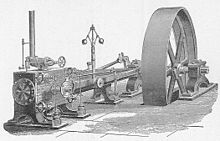

Many were quite large, standing many metres tall and developing several hundred horsepower, albeit at low speed, turning massive flywheels weighing several tons at about 100 revolutions per minute.

Some of these engines have unusual roles as mechanical legacy systems and because of their relatively high efficiency and low maintenance requirements, some remain in service into the early 21st century.

Clark (1891) commented that the Corliss gear "is essentially a combination of elements previously known and used separately, affecting the cylinder and the valve-gear".

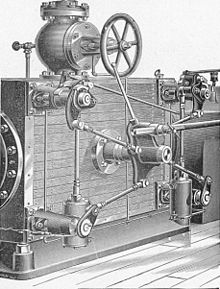

The speed of a Corliss engine is controlled by varying the cutoff of steam during each power stroke, while leaving the throttle wide open at all times.

These cams determine the point during the piston stroke that the pawl will release, allowing that valve to close.

The Corliss valve gearing allowed more uniform speed and better response to load changes, making it suitable for applications like rolling mills and spinning, and greatly expanding its use in manufacturing.

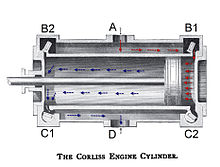

Corliss valves are in the form of a minor circular segment, rotating inside a cylindrical valve-face.

Gas-flow forces acting asymmetrically on this butterfly could lead to poor control of the power in some circumstances.

[9] A common feature of large Corliss engines is one or two sets of narrow gear teeth in the rim of the flywheel.

so it is common to admit low-pressure steam to both sides of the cylinder to warm up the metalwork.

In 1848 the company moved to the Charles Street Railroad Crossing in Providence, Rhode Island.

Patents granted to Corliss and others incorporated rotary valves and crank shafts in-line with the cylinders.

[15] Competing inventors worked hard to invent alternatives to Corliss' mechanisms; they generally avoided Corlis's use of a wrist plate and adopted alternative releasing mechanisms for the steam valves, as in Jamieson's U.S. Patent 19,640, granted March 16, 1858.

[20] In 1905 it was transferred to another Hoadley's firm, the American & British Manufacturing Corporation [de].

The Corliss Centennial Engine was an all-inclusive, specially built rotative beam engine that powered virtually all of the exhibits at the United States Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 through shafts totaling over a mile in length.

Switched on by President Ulysses S. Grant and Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, the engine was in public view for the duration of the fair.