Matthew Murray

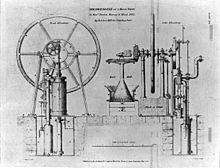

He was an innovative designer in many fields, including steam engines, machine tools and machinery for the textile industry.

John Marshall had rented a small mill at Adel, for the purpose of manufacture but also to develop a pre-existing flax-spinning machine, with the aid of Matthew Murray.

Industry in the Leeds area was developing fast and it became apparent that there was an opportunity for a firm of general engineers and millwrights to set up.

Murray ingeniously got round this difficulty by introducing a Tusi couple hypocycloidal straight line mechanism.

Matthew Murray improved the working of these valves by driving them with an eccentric gear attached to the rotating shaft of the engine.

[2] The success that Fenton, Murray and Wood enjoyed because of the high quality of their workmanship attracted the hostility of competitors, Boulton and Watt.

There was also an attempt by the firm of Boulton and Watt to obtain information from an employee of Fenton, Murray and Wood by bribery.

Finally, James Watt jnr purchased land adjacent to the workshop in an attempt to prevent the firm from expanding.

Murray's patent of 1801, for improved air pumps and other innovations, and of 1802, for a self-contained compact engine with a new type of slide valve, were contested and overturned.

[2] In 1812 the firm supplied John Blenkinsop, manager of Brandling's Middleton Colliery, near Leeds, with the first twin-cylinder steam locomotive (Salamanca).

Because only a lightweight locomotive could work on cast iron rails without breaking them, the total load they were capable of hauling was very much limited.

Once a system had been devised for making malleable iron rails, around 1819, the rack and pinion motion became unnecessary, apart from later use on mountain railways.

The third locomotive intended for Middleton was sent, at Blenkinsop's request, to the Kenton and Coxlodge Colliery waggonway near Newcastle upon Tyne, where it appears to have been known as Willington.

[2] After two of the locomotives exploded, killing their drivers, and the remaining two were increasingly unreliable after at least 20 years’ hard labour, the Middleton colliery eventually reverted to horse haulage in 1835.

In 1811 the firm made a Trevithick-pattern high-pressure steam engine for John Wright, a Quaker of Great Yarmouth, Norfolk.

At the time when these inventions were made the flax trade was on the point of expiring, the spinners being unable to produce yarn to a profit.

The effect of his inventions was to reduce the cost of production, and improve the quality of the manufacture, thus establishing the British linen trade on a solid foundation.

The production of flax-machinery became an important branch of manufacture at Leeds, large quantities being made for use at home as well as for exportation, giving employment to an increasing number of highly skilled mechanics.

Several prominent engineers were trained there, including Benjamin Hick, Charles Todd, David Joy and Richard Peacock.

Murray's only son Matthew (c.1793–1835)[8] served an apprenticeship at the Round Foundry and went to Russia; he founded an engineering business in Moscow,[2] where he died age 42.