Broiler

[3] Due to extensive breeding selection for rapid early growth and the husbandry used to sustain this, broilers are susceptible to several welfare concerns, particularly skeletal malformation and dysfunction, skin and eye lesions and congestive heart conditions.

Management of ventilation, housing, stocking density and in-house procedures must be evaluated regularly to support good welfare of the flock.

The breeding stock (broiler-breeders) do grow to maturity but also have their own welfare concerns related to the frustration of a high feeding motivation and beak trimming.

Before the development of modern commercial meat breeds, broilers were mostly young male chickens culled from farm flocks.

Besides the breeds normally favored, Cornish Game, Plymouth Rock, New Hampshire, Langshans, Jersey Black Giant, and Brahmas were included.

Broiler breeds have been selected specifically for growth, causing them to develop large pectoral muscles, which interfere with and reduce natural mating.

[12] Modern commercial broilers, for example, Cornish crosses and Cornish-Rocks,[citation needed] are artificially selected and bred for large-scale, efficient meat production.

Recent genetic analysis has revealed that the gene for yellow skin was incorporated into domestic birds through hybridization with the grey junglefowl (G. sonneratii).

[15] Modern crosses are also favorable for meat production because they lack the typical "hair" which many breeds have that must be removed by singeing after plucking the carcass.

[16] The same study shows that in the outdoors group, surprisingly little use is made of the extra space and facilities such as perches – it was proposed that the main reason for this was leg weakness as 80 per cent of the birds had a detectable gait abnormality at seven weeks of age.

The decline in libido is not enough to account for reduced fertility in heavy cocks at 58 weeks and is probably a consequence of the large bulk or the conformation of the males at this age interfering in some way with the transfer of semen during copulations which otherwise look normal.

[2] Breeding for increased breast muscle affects the way chickens walk and puts additional stresses on their hips and legs.

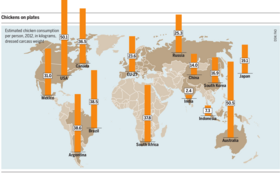

Mass production of chicken meat is a global industry and at that time, only two or three breeding companies supplied around 90% of the world's breeder-broilers.

[27] Average daily temperatures of around 33 °C (91 °F) are known to interfere with feeding in both broilers and egg hens, as well as lower their immune response, with outcomes such as reduced weight gain/egg production or greater incidence of salmonella infections, footpad dermatitis or meningitis.

Multiple studies show that dietary supplementation with chromium can help to relieve these issues due to its antioxidative properties, particularly in combination with zinc or herbs like wood sorrel.

[34] Though the effect of supplementation is limited, it is much cheaper than interventions to improve cooling or simply stock fewer birds, and so remains popular.

[35] While the majority of literature on poultry heat stress and dietary supplementation focuses on chickens, similar findings were seen in Japanese quails, which eat less and gain less weight, suffer reduced fertility and hatch eggs of worse quality under heat stress, and also seem to benefit from mineral supplementation.