Coronal mass ejection

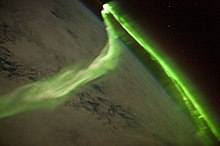

ICMEs are capable of reaching and colliding with Earth's magnetosphere, where they can cause geomagnetic storms, aurorae, and in rare cases damage to electrical power grids.

CMEs release large quantities of matter from the Sun's atmosphere into the solar wind and interplanetary space.

However, the estimated mass values for CMEs are only lower limits, because coronagraph measurements provide only two-dimensional data.

Pre-eruption structures originate from magnetic fields that are initially generated in the Sun's interior by the solar dynamo.

Pre-eruption CME structures can be present at different stages of the growth and decay of these regions, but they always lie above polarity inversion lines (PIL), or boundaries across which the sign of the vertical component of the magnetic field reverses.

[1][2] In order for pre-eruption CME structures to develop, large amounts of energy must be stored and be readily available to be released.

[3][6] Some pre-eruption structures have been observed to support prominences, also known as filaments, composed of much cooler material than the surrounding coronal plasma.

The processes involved in the early evolution of CMEs are poorly understood due to a lack of observational evidence.

The specific processes involved in CME initiation are debated, and various models have been proposed to explain this phenomenon based on physical speculation.

In cases where significant magnetic reconnection does not occur, ideal MHD instabilities or the dragging force from the solar wind can theoretically accelerate a CME.

However, if sufficient acceleration is not provided, the CME structure may fall back in what is referred to as a failed or confined eruption.

[6][3] A coronal dimming is a localized decrease in extreme ultraviolet and soft X-ray emissions in the lower corona.

[16] Observations of CMEs are typically through white-light coronagraphs which measure the Thomson scattering of sunlight off of free electrons within the CME plasma.

CMEs can experience aerodynamic drag forces that act to bring them to kinematic equilibrium with the solar wind.

Aerodynamic drag and snowplow models assume that ICME evolution is governed by its interactions with the solar wind.

The strongest deceleration or acceleration occurs close to the Sun, but it can continue even beyond Earth orbit (1 AU), which was observed using measurements at Mars[21] and by the Ulysses spacecraft.

Historical records show that the most extreme space weather events involved multiple successive CMEs.

For example, the famous Carrington event in 1859 had several eruptions and caused auroras to be visible at low latitudes for four nights.

Other signatures of magnetic clouds are now used in addition to the one described above: among other, bidirectional superthermal electrons, unusual charge state or abundance of iron, helium, carbon, and/or oxygen.

When the magnetosphere reconnects on the nightside, it releases power on the order of terawatts directed back toward Earth's upper atmosphere.

[40] The interaction of CMEs with the Earth's magnetosphere leads to dramatic changes in the outer radiation belt, with either a decrease or an increase of relativistic particle fluxes by orders of magnitude.

[quantify][41] The changes in radiation belt particle fluxes are caused by acceleration, scattering and radial diffusion of relativistic electrons, due to the interactions with various plasma waves.

[44] In 2019, researchers used an alternative method (Weibull distribution) and estimated the chance of Earth being hit by a Carrington-class storm in the next decade to be between 0.46% and 1.88%.

[6] The largest recorded geomagnetic perturbation, resulting presumably from a CME, coincided with the first-observed solar flare on 1 September 1859.

[46] The discovery image (256 × 256 pixels) was collected on a Secondary Electron Conduction (SEC) vidicon tube, transferred to the instrument computer after being digitized to 7 bits.

David Roberts, an electronics technician working for NRL who had been responsible for the testing of the SEC-vidicon camera, was in charge of day-to-day operations.

But on the next image the bright area had moved away from the Sun and he immediately recognized this as being unusual and took it to his supervisor, Dr. Guenter Brueckner,[47] and then to the solar physics branch head, Dr. Tousey.

The spacecraft is a spin axis-stabilized satellite that carries eight instruments measuring solar wind particles from thermal to greater than MeV energies, electromagnetic radiation from DC to 13 MHz radio waves, and gamma-rays.

[citation needed] On 25 October 2006, NASA launched STEREO, two near-identical spacecraft which, from widely separated points in their orbits, are able to produce the first stereoscopic images of CMEs and other solar activity measurements.

The New Horizons spacecraft was at 31.6 AU approaching Pluto when the CME passed three months after the initial eruption, and it may be detectable in the data.