Coronavirus

[6] They have characteristic club-shaped spikes that project from their surface, which in electron micrographs create an image reminiscent of the stellar corona, from which their name derives.

[7] The name refers to the characteristic appearance of virions (the infective form of the virus) by electron microscopy, which have a fringe of large, bulbous surface projections creating an image reminiscent of the solar corona or halo.

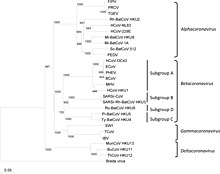

[12] As the number of new species increased, the genus was split into four genera, namely Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Deltacoronavirus, and Gammacoronavirus in 2009.

In 1965, Tyrrell and Bynoe successfully cultivated the novel virus by serially passing it through organ culture of human embryonic trachea.

[28] The isolated virus when intranasally inoculated into volunteers caused a cold and was inactivated by ether which indicated it had a lipid envelope.

[30][31] Scottish virologist June Almeida at St Thomas' Hospital in London, collaborating with Tyrrell, compared the structures of IBV, B814 and 229E in 1967.

[32][33] Using electron microscopy the three viruses were shown to be morphologically related by their general shape and distinctive club-like spikes.

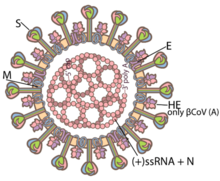

The S2 subunit forms the stem which anchors the spike in the viral envelope and on protease activation enables fusion.

The two subunits remain noncovalently linked as they are exposed on the viral surface until they attach to the host cell membrane.

An exception is the MHV NTD that binds to a protein receptor carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1).

[45] A subset of coronaviruses (specifically the members of betacoronavirus subgroup A) also has a shorter spike-like surface protein called hemagglutinin esterase (HE).

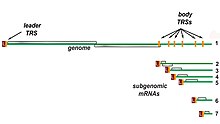

[49] The larger polyprotein pp1ab is a result of a -1 ribosomal frameshift caused by a slippery sequence (UUUAAAC) and a downstream RNA pseudoknot at the end of open reading frame ORF1a.

[63] The exact mechanism of recombination in coronaviruses is unclear, but likely involves template switching during genome replication.

The interaction of the coronavirus spike protein with its complementary cell receptor is central in determining the tissue tropism, infectivity, and species range of the released virus.

[42] SARS coronavirus, for example, infects the human epithelial cells of the lungs via an aerosol route[68] by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.

[69] Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) infects the pig epithelial cells of the digestive tract via a fecal–oral route[67] by binding to the alanine aminopeptidase (APN) receptor.

The large number and global range of bat and avian species that host viruses have enabled extensive evolution and dissemination of coronaviruses.

[87] Besides causing respiratory infections, human coronavirus OC43 is also suspected of playing a role in neurological diseases.

In 2003, following the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) which had begun the prior year in Asia, and secondary cases elsewhere in the world, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a press release stating that a novel coronavirus identified by several laboratories was the causative agent for SARS.

Two confirmed cases involved people who seemed to have caught the disease from their late father, who became ill after a visit to Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

[116] In May 2015, an outbreak of MERS-CoV occurred in the Republic of Korea, when a man who had traveled to the Middle East, visited four hospitals in the Seoul area to treat his illness.

[117] As of December 2019, 2,468 cases of MERS-CoV infection had been confirmed by laboratory tests, 851 of which were fatal, a mortality rate of approximately 34.5%.

[119] On 31 December 2019, the outbreak was traced to a novel strain of coronavirus,[120] which was given the interim name 2019-nCoV by the World Health Organization,[121][122][123] later renamed SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.

[125][126] During a surveillance study of archived samples of Malaysian viral pneumonia patients, virologists identified a strain of canine coronavirus which has infected humans in 2018.

[19] They infect a range of animals including swine, cattle, horses, camels, cats, dogs, rodents, birds and bats.

[128] Significant research efforts have been focused on elucidating the viral pathogenesis of these animal coronaviruses, especially by virologists interested in veterinary and zoonotic diseases.

[131] The virus is of concern to the poultry industry because of the high mortality from infection, its rapid spread, and its effect on production.

[135] Transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), which is a member of the species Alphacoronavirus 1,[136] is another coronavirus that causes diarrhea in young pigs.

[137][138] In the cattle industry bovine coronavirus (BCV), which is a member of the species Betacoronavirus 1 and related to HCoV-OC43,[139] is responsible for severe profuse enteritis in young calves.

Some strains of MHV cause a progressive demyelinating encephalitis in mice which has been used as a murine model for multiple sclerosis.