Cosmic Background Explorer

Its goals were to investigate the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB or CMBR) of the universe and provide measurements that would help shape the understanding of the cosmos.

COBE's measurements provided two key pieces of evidence that supported the Big Bang theory of the universe: that the CMB has a near-perfect black-body spectrum, and that it has very faint anisotropies.

Two of COBE's principal investigators, George F. Smoot III and John C. Mather, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2006 for their work on the project.

The purpose of the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) mission was to take precise measurements of the diffuse radiation between 1 micrometre and 1 cm (0.39 in) over the whole celestial sphere.

It would contain the following instruments:[6] NASA accepted the proposal provided that the costs be kept under US$30 million, excluding launcher and data analysis.

"[8] The Nobel Prize in Physics for 2006 was jointly awarded to John C. Mather, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and George F. Smoot III, University of California, Berkeley, "for their discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation".

[10] The instruments required temperature stability and to maintain gain, and a high level of cleanliness to reduce entry of stray light and thermal emission from particulates.

[10] The spin axis is also tilted back from the orbital velocity vector as a precaution against possible deposits of residual atmospheric gas on the optics as well against the infrared glow that would result from fast neutral particles hitting its surfaces at extremely high speed.

A 900 km (560 mi) altitude orbit with a 99° inclination was chosen as it fit within the capabilities of either a Space Shuttle (with an auxiliary propulsion on COBE) or a Delta launch vehicle.

The orbit combined with the spin axis made it possible to keep the Earth and the Sun continually below the plane of the shield, allowing a full sky scan every six months.

The conical Sun-Earth shield protected the instruments from direct solar and Earth-based radiation as well as radio interference from Earth and the COBE's transmitting antenna.

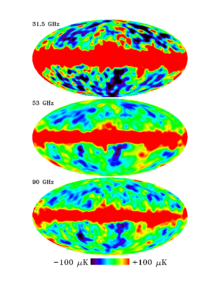

Each radiometer employs a pair of horn antennas viewing at 30° from the spin axis of the spacecraft, measuring the differential temperature between points in the sky separated by 60°.

Each radiometer is a microwave receiver whose input is switched rapidly between the two horn antennas, obtaining the difference in brightness of two fields of view 7° in diameter located 60° apart and 30° from the axis of the spacecraft.

The instrument has a differential input to compare the sky with an internal reference at 3 K. This feature provides immunity from systematic errors in the spectrometer and contributes significantly to the ability to detect small deviations from a blackbody spectrum.

[16] The DMR was able to spend four years mapping the detectable anisotropy of cosmic background radiation as it was the only instrument not dependent on the dewar's supply of helium to keep it cooled.

The cosmic microwave background fluctuations are extremely faint, only one part in 100,000 compared to the 2.73 K average temperature of the radiation field.

The cosmic microwave background radiation is a remnant of the Big Bang and the fluctuations are the imprint of density contrast in the early universe.

It was found that this cloud, which as seen from Earth is Zodiacal light, was not centered on the Sun, as previously thought, but on a place in space a few million kilometers away.

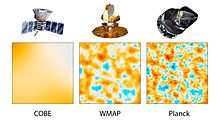

On 30 June 2001, NASA launched a follow-up mission to COBE led by DMR Deputy Principal Investigator Charles L. Bennett.

Following WMAP, the European Space Agency's probe, Planck has continued to increase the resolution at which the background has been mapped.