Cotton Mather

After being educated at Harvard College, he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting House in Boston, then part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where he preached for the rest of his life.

[2] A major intellectual and public figure in English-speaking colonial America, Cotton Mather helped lead the successful revolt of 1689 against Sir Edmund Andros, the governor of New England appointed by King James II.

Mather's subsequent involvement in the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693, which he defended in the book Wonders of the Invisible World (1693), attracted intense controversy in his own day and has negatively affected his historical reputation.

James's intention was to curb Massachusetts's religious separatism by incorporating the colony it into a larger Dominion of New England, without an elected legislature and under a governor who would serve at the pleasure of the Crown.

Cotton Mather's reputation, in his own day as well as in the historiography and popular culture of subsequent generations, has been very adversely affected by his association with the events surrounding the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693.

Although Mather had no official role in the legal proceedings,[22] he wrote the book Wonders of the Invisible World, which appeared in 1693 with the endorsement of William Stoughton, the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts and chief judge of the Salem witch trials.

According to Jan Stievermann, of the Heidelberg Center for American Studies, unlike some other ministers [Cotton Mather] never called for an end to the trials, and he afterwards wrote New England's official defense of the court's proceedings, the infamous Wonders of the Invisible World (1693).

[25]In 1689, Mather published Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions, based on his study of events surrounding the affliction of the children of a Boston mason named John Goodwin.

[31]Similar views, on Mather's responsibility for the climate of hysteria over witchcraft that led to the Salem trials, were repeated by later commentators, such as the politician and historian Charles W. Upham in the 19th century.

[33] In May of that year, Sir William Phips, governor of the newly chartered Province of Massachusetts Bay, appointed a special "Court of Oyer and Terminer" to try the cases of witchcraft in Salem.

He also wrote that the identification and conviction of all witches should be undertaken with the greatest caution and warned against the use of spectral evidence (i.e., testimony that the specter of the accused had tormented a victim) on the grounds that devils could assume the form of innocent and even virtuous people.

[35] On June 10, 1692, Bridget Bishop, the thrice-married owner of an unlicensed tavern, was hanged after being convicted and sentenced by the Court of Oyer and Terminer, based largely on spectral evidence.

[36] Robert Calef would later criticize Mather's intervention in The Return of Several Ministers as "perfectly ambidexter, giving a great or greater encouragement to proceed in those dark methods, than cautions against them.

"[37] On August 4, Cotton Mather preached a sermon before his North Church congregation on the text of Revelation 12:12: "Woe to the Inhabitants of the Earth, and of the Sea; for the Devil is come down unto you, having great Wrath; because he knoweth, that he hath but a short time.

According to his Mather's contemporary critic Robert Calef, the crowd was disturbed by George Burroughs's eloquent declarations of innocence from the scaffold and by his recitation of the Lord's Prayer, of which witches were commonly believed to be incapable.

And this did somewhat appease the People, and the Executions went on.As public discontent with the witch trials grew in the summer of 1692, threatening civil unrest, the conservative Cotton Mather felt compelled to defend the responsible authorities.

[40] On September 2, 1692, after eleven people had been executed as witches, Cotton Mather wrote a letter to Judge Stoughton congratulating him on "extinguishing of as wonderful a piece of devilism as has been seen in the world".

At around the same time that the book began to circulate in manuscript form, Governor Phips decided to restrict greatly the use of spectral evidence, thus raising a high barrier against further convictions.

Genuinely Anglo-American in outlook, the book projects a New England which is ultimately an enlarged version of Cotton Mather himself, a pious citizen of "The Metropolis of the whole English America".

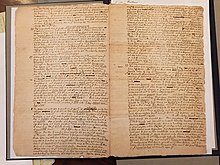

[48] In 1693 Mather also began work on a grand intellectual project that he titled Biblia Americana, which sought to provide a commentary and interpretation of the Christian Bible in light of "all of the Learning in the World".

Contrary to the promises that he had made to the Mathers, Governor Dudley proved a divisive and high-handed executive, reserving his patronage for a small circle composed of transatlantic merchants, Anglicans, and religious liberals such as Thomas Brattle, Benjamin Colman, and John Leverett.

Mather then declared, in a letter to Dr John Woodward of Gresham College in London, that he planned to press Boston's doctors to adopt the practice of inoculation should smallpox reach the colony again.

He believed that not all learned individuals were qualified to doctor others, and while ministers took on several roles in the early years of the colony, including that of caring for the sick, they were now expected to stay out of state and civil affairs.

"[90][full citation needed] While Mather was experimenting with the procedure, prominent Puritan pastors Benjamin Colman and William Cooper expressed public and theological support for them.

Although many were initially wary of the concept, it was because people were able to witness the procedure's consistently positive results, within their own community of ordinary citizens, that it became widely utilized and supported.

After overcoming considerable difficulty and achieving notable success, Boylston traveled to London in 1725, where he published his results and was elected to the Royal Society in 1726, with Mather formally receiving the honor two years prior.

[96] He also argued against the spontaneous generation of life and compiled a medical manual titled The Angel of Bethesda that he hoped would assist people who were unable to procure the services of a physician, but which went unpublished in Mather's lifetime.

Mather also outlined an early form of germ theory and discussed psychogenic diseases, while recommending hygiene, physical exercise, temperate diet, and avoidance of tobacco smoking.

[106] Like the majority of Christians at the time, but unlike his political rival Judge Samuel Sewall, Mather was never an abolitionist, although he did publicly denounce what he regarded as the illegal and inhuman aspects of the burgeoning Atlantic slave trade.

Concerned about the New England sailors enslaved in Africa since the 1680s and 1690s, in 1698 Mather wrote them his Pastoral Letter to the Captives, consoling them, and expressing hope that “your slavery to the monsters of Africa will be but short.”[107] On the return of some survivors of African slavery in 1703, Mather published The History of What the Goodness of God has done for the Captives, lately delivered out of Barbary, wherein he lamented the death of multiple American slaves, the length of their captivity—which he described as between 7 and 19 years,—the harsh conditions of their bondage, and celebrated their refusal to convert to Islam, unlike others who did.