Council of the European Union

The precise membership of these configurations varies according to the topic under consideration; for example, when discussing agricultural policy the Council is formed by the 27 national ministers whose portfolio includes this policy area (with the related European Commissioners contributing but not voting).

Due to disagreements between French President Charles de Gaulle and the Commission's agriculture proposals, among other things, France boycotted all meetings of the Council.

This halted the Council's work until the impasse was resolved the following year by the Luxembourg compromise.

However, at the same time the Parliament and Commission had been strengthened inside the Community pillar, curtailing the ability of the Council to act independently.

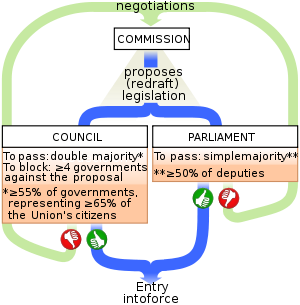

[14] The primary purpose of the Council is to act as one of two vetoing bodies of the EU's legislative branch, the other being the European Parliament.

Finally, before the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, it formally held the executive power of the EU which it conferred upon the European Commission.

[17][18][19] The Council represents the executive governments of the EU's member states[2][15] and is based in the Europa building in Brussels.

[15] In early times, the avis facultatif maxim was: "The Commission proposes, and the Council disposes";[22] but now the vast majority of laws are subject to the ordinary legislative procedure, which works on the principle that consent from both the Council and Parliament are required before a law may be adopted.

If a Committee manages to adopt a joint text, it then has to be approved in a third reading by both the Council and Parliament or the proposal is abandoned.

Then there are directives which bind members to certain goals which they must achieve, but they do this through their own laws and hence have room to manoeuvre in deciding upon them.

Usually the Council's intention is to set out future work foreseen in a specific policy area or to invite action by the Commission.

[32] The legal instruments used by the Council for the Common Foreign and Security Policy are different from the legislative acts.

Common positions relate to defining a European foreign policy towards a particular third-country such as the promotion of human rights and democracy in Myanmar, a region such as the stabilisation efforts in the African Great Lakes, or a certain issue such as support for the International Criminal Court.

A common position, once agreed, is binding on all EU states who must follow and defend the policy, which is regularly revised.

Common strategies defined an objective and commits the EUs resources to that task for four years.

[34] An exception to this rule exists via Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union, which stipulates circumstances in which qualified majority voting is permissible for the Council in discussing Common Foreign and Security Policy.

[35][37] Additionally, Article 31 stipulates derogation for "a decision defining a Union action or position".

[35][37] In late 2023 and early 2024, unanimity voting on foreign affairs issues by the Council made headlines due to the resistance of Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary, to passing European Union aid to Ukraine.

The EU's budget (which is around 155 billion euro)[41] is subject to a form of the ordinary legislative procedure with a single reading giving Parliament power over the entire budget (prior to 2009, its influence was limited to certain areas) on an equal footing with the Council.

From 2007, every three member states co-operate for their combined eighteen months on a common agenda, although only one formally holds the presidency for the normal six-month period.

[43][44] The exception however is the foreign affairs council, which has been chaired by the High Representative since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty.

Similarly, the Economic and Financial Affairs Council is composed of national finance ministers, and they are still one per state and the chair is held by the member coming from the presiding country.

As of 2020[update], there are ten formations:[48][49] Complementing these, the Political and Security Committee (PSC) brings together ambassadors to monitor international situations and define policies within the CSDP, particularly in crises.

However, the broad ideological alignment of the government in each state does influence the nature of the law the Council produces and the extent to which the link between domestic parties puts pressure on the members in the European Parliament to vote a certain way.

[66] Between 1952 and 1967, the ECSC Council held its Luxembourg City meetings in the Cercle Municipal on Place d'Armes.

In practice this was to be in the Château of Val-Duchesse until the autumn of 1958, at which point it moved to 2 Rue Ravensteinstraat in Brussels.

[clarification needed] However, its staff was still increasing, so it continued to rent the Frère Orban building to house the Finnish and Swedish language divisions.

Staff continued to increase and the Council rented, in addition to owning Justus Lipsius, the Kortenberg, Froissart, Espace Rolin, and Woluwe Heights buildings.

The focal point of the new building, the distinctive multi-storey "lantern" shaped structure in which the main meeting room is located, is utilised in both EU institutions' new official logos.