Countable set

[a] Equivalently, a set is countable if there exists an injective function from it into the natural numbers; this means that each element in the set may be associated to a unique natural number, or that the elements of the set can be counted one at a time, although the counting may never finish due to an infinite number of elements.

In more technical terms, assuming the axiom of countable choice, a set is countable if its cardinality (the number of elements of the set) is not greater than that of the natural numbers.

[2][3] The terms enumerable[4] and denumerable[5][6] may also be used, e.g. referring to countable and countably infinite respectively,[7] definitions vary and care is needed respecting the difference with recursively enumerable.

[16] In 1878, he used one-to-one correspondences to define and compare cardinalities.

[17] In 1883, he extended the natural numbers with his infinite ordinals, and used sets of ordinals to produce an infinity of sets having different infinite cardinalities.

One way is simply to list all of its elements; for example, the set consisting of the integers 3, 4, and 5 may be denoted

, this gives us the usual definition of "sets of size

,[a] has infinitely many elements, and we cannot use any natural number to give its size.

We call all sets that are in one-to-one correspondence with the integers countably infinite and say they have cardinality

, and vice versa, this defines a bijection, and shows that

Similarly we can show all finite sets are countable.

We can show these sets are countably infinite by exhibiting a bijection to the natural numbers.

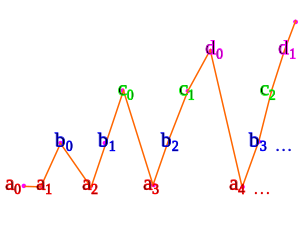

This form of triangular mapping recursively generalizes to

are natural numbers, by repeatedly mapping the first two elements of an

-tuples made by the Cartesian product of finitely many different sets, each element in each tuple has the correspondence to a natural number, so every tuple can be written in natural numbers then the same logic is applied to prove the theorem.

are integers), then for every positive fraction, we can come up with a distinct natural number corresponding to it.

[c] In a similar manner, the set of algebraic numbers is countable.

to be shown as countable is one-to-one mapped (injection) to another set

For example, the set of positive rational numbers can easily be one-to-one mapped to the set of natural number pairs (2-tuples) because

Since the set of natural number pairs is one-to-one mapped (actually one-to-one correspondence or bijection) to the set of natural numbers as shown above, the positive rational number set is proved as countable.

[24][25][e] With the foresight of knowing that there are uncountable sets, we can wonder whether or not this last result can be pushed any further.

The answer is "yes" and "no", we can extend it, but we need to assume a new axiom to do so.

We need the axiom of countable choice to index all the sets

Theorem — The set of all finite-length sequences of natural numbers is countable.

Theorem — The set of all finite subsets of the natural numbers is countable.

These follow from the definitions of countable set as injective / surjective functions.

As an immediate consequence of this and the Basic Theorem above we have: Proposition — The set

For an elaboration of this result see Cantor's diagonal argument.

The Löwenheim–Skolem theorem can be used to show that this minimal model is countable.

The fact that the notion of "uncountability" makes sense even in this model, and in particular that this model M contains elements that are: was seen as paradoxical in the early days of set theory; see Skolem's paradox for more.