County magistrate

Education in the Confucian Classics included no practical training, but indoctrinated the officials with a shared ideology which helped to unify the empire.

Promotion depended on the magistrate's ability to maintain peace and lawful order as he supervised tax collection, roads, water control, and the census; handled legal functions as both prosecutor and judge; arranged relief for the poor or the afflicted; carried out rituals; encouraged education and schools; and performed any further task that the emperor chose to assign.

Instead, he was an all-around blunderer, a harassed Jack-of-all trades...." [2] The Republic of China made extensive reforms in county government, but the position of magistrate was retained.

[6] Before the Qin unification in 221 BCE, local officials inherited office, which strengthened great families against the central government.

Imperial power undercut the local aristocracy by appointing scholar officials chosen by merit through the examination system who were not necessarily of noble descent.

The Han dynasty regularized the position, and initiated the "rule of avoidance", which forbade a magistrate to serve in his home county because of the danger of nepotism and favoritism to family or friends.

[9] In the Ming and Qing dynasties the growth of the economy and increase in population led magistrates to hire administrative secretaries and to rely on local elite families, or scholar-gentry.

[1] When the People's Republic was founded in 1949, the central government once again appointed local officials who wielded civil, criminal, and bureaucratic power.

Some suggest that workers and villagers feel they cannot question the authority of these "father and mother" officials, making corruption easier and dissent harder.

The emperors believed that Heaven entrusted their government with relations with the physical universe, cosmic morality, human institutions, and social harmony, and the magistrate was his representative in all these matters.

In the counties of the prosperous Lower Yangzi valley, the total staff of clerks, secretaries, yamen runners, medical examiners, jailers, and other such lesser employees might be some 500 people for a population of 100,000 to 200,000.

[4] The eminent historian Kung-chuan Hsiao, however, argued that local government became more despotic and the county magistrate had unlimited powers to control the people.

Each village was required to contribute free labor, or the corvee, for building and maintaining local roads, canals, and dams under the supervision of the county government.

He was allowed to keep a specified amount for local functions such as salaries, stipends for government school students, and relief for the poor, then forward the rest to the provincial treasurer.

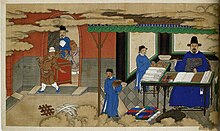

[17] The magistrate lived, worked, and held court in the yamen, a walled compound which housed the local government.

In theory, any commoner could submit a lawsuit, petition, or complaint after striking a large bell at the entrance to the compound.

Cases ranged from murder and theft to accusations that a neighbor did not tie his horse or dog or that someone had been kicked or bitten.

He decided which cases to accept, directed the gathering of evidence and witnesses, then conducted the trial, including the use of torture.

Since he could be reprimanded for not investigating thoroughly, for not following correct procedure, or even for writing the wrong character, magistrates in later dynasties hired specialized clerks or secretaries who had expertise in the law and bureaucratic requirements.

When the accused was brought before him, the magistrate could use torture, such as flogging or making the defendant kneel on an iron chain, but there were clear restrictions.

Ming rulers tightened the rule of avoidance which prevented magistrates from serving in their home districts, where it was justifiably feared that they would favor their friends and families, and the term of office was generally limited to two or three years.

Confucian ideals also held that the state should stay out of the lives of the common people, who were to carry out public security functions on their own.

In the 1720s the Yongzheng Emperor allowed the magistrate to deduct "meltage fees" from the land tax he was required to remit, but this did not address the structural problem.

Many of these unassigned men took positions as secretaries or clerks to county magistrates, forming a virtual sub-profession of experts on various aspects of the law, water-works, taxation, or administration.

[22] The law of avoidance remained in effect, though it too was no longer enforced rigorously, and the political chaos of the period was reflected in rapid turnover and shorter terms of office.

[23] In the years leading up to the founding of the Nationalist government in 1928, however, there was a noticeable improvement in the education and technical training of the magistrates, particularly in law and administration.

They became the heads of the county after the central government streamlined all provinces which effectively downsized to non-self-governing bodies in 1998, and in 2019 all provincial governmental organs were formally abolished.