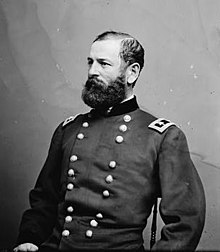

Court-martial of Fitz John Porter

Major General Fitz John Porter was found guilty of disobeying a lawful order and misconduct in front of the enemy, and was removed from command based on internal political machinations of the Union Army.

As he moved his corps into position at Aquia Creek near Fredericksburg, Porter sent a number of telegrams to Major General Ambrose Burnside complaining about Pope's poor leadership and handling of the army.

[4] Burnside, who, along with many others, shared Porter's low opinion of Pope's abilities, forwarded these communications to McClellan, General-in-Chief Henry Halleck, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and President Abraham Lincoln.

McDowell, the senior commander, decided to not move the two corps to Gainesville and attack, but, for unknown reasons, did not forward Buford's report to Pope.

The enemy is massed in the woods in front of us, but can be shelled out as soon as you engage their flank... At 4:30 pm, Pope, frustrated that no attack was occurring on Jackson's right flank and still unaware of Longstreet's presence, despite numerous reports of a large Confederate force forming west of his position, sent an explicit order to attack by way of his nephew.

Even had the message been on time, it was impossible for Porter to both move forward and attack Jackson's right flank and maintain contact with Brigadier General John F. Reynolds's division of McDowell's corps.

In what was arguably the most famous incident of the battle, some Confederate brigades fired so much that they ran out of ammunition and resorted to throwing large rocks.

To support Jackson's exhausted defense, Longstreet's artillery added to the barrage against Union reinforcements attempting to move in, cutting them to pieces.

A bold defensive by several brigades on Chinn Ridge, then of Henry Hill, was all that enabled the Union to stabilize the situation and retreat from Manassas in an orderly fashion.

In the weeks following the battle, McClellan failed to take any decisive action and Lee's army slipped back into Virginia to regroup and fight again.

[8] In the first charge, Pope – through his inspector general – was trying to prove that Porter's failure to follow his orders resulted in the situation which gave the Confederates the upper hand on the battlefield.

Of particular importance to Pope was the assertion that if Porter had moved at 1:00 am as ordered, Longstreet would have been unable to take up the close position on Jackson's right flank and then the Confederates behind the unfinished railroad grade might have been dislodged.

He was a staunchly conservative Democrat who had supported Stephen Douglas against Lincoln and who had argued on behalf of the slave-owning defendant in the infamous Dred Scott case.

McDowell, in the midst of answering to his own court of inquiry regarding actions during the battle that had led to his virtual banishment from the army, was an eager cooperator in pinning much of the blame for the loss on Porter.

Even more damaging than the testimony of prominent Republican generals was that the only maps used during the trial were supplied by Pope and substantiated his version of the time-line for the positioning of Longstreet's corps.

[12] On January 21, the court ordered Fitz John Porter cashiered, or dismissed from the army for disciplinary reasons, and "forever disqualified from holding any office of trust or profit under the Government of the United States.

Coupled with the disastrous loss at Fredericksburg, the near mutiny of Burnside's officers after the Mud March, and the resurgence of the Democratic Party, which was increasingly calling for negotiated settlement, the trial severely unsettled the public perception of competence in the army and administration.

Not long after he had testified as an administration witness against Porter, McDowell's court of inquiry exonerated him of wrongdoing at the Second Battle of Bull Run and recommended he be returned to command.

The New York Times opined that not only was Porter's crusade to overturn his conviction immoral in that it encouraged dissent in the ranks, but that the general himself ought to have been executed.

[16] When the war ended, Porter wrote to both Lee and Longstreet asking for their assistance in the matter and also petitioned to be allowed access to captured papers of the Confederacy.

[17] Resolutions demanding his case be reopened and equally fierce denunciations of those resolution had swirled on the local and national level, barely slowed since January 1863,[18] but Porter supporters – now including such famous generals as Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and George H. Thomas, which contributed greatly to their rapid decline in popularity with their own party – were finally gaining enough headway to reexamine the issue.

Finally, in 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes commissioned a board under Major General John Schofield, who had briefly replaced Stanton as Secretary of War after Johnson forced him out, to investigate.

Schofield was joined by Brigadier General Alfred Terry, in between stints commanding U.S. forces in the Dakota Territory, and Colonel (since wartime brevets had reverted to regular army ranks) George W. Getty, who had been part of Burnside's corps that had not made it in time to the battlefield near Manassas in August 1862.

They reviewed the extensive evidence compiled by Porter during the intervening years and conducted interviews of their own with principals from both sides of the fighting on the day of the battle.

On March 19, 1879, the commission issued a report to President Hayes recommending that "justice requires at [the President's] hands such action as may be necessary to annul and set aside the findings and sentence of the court-martial in the case of Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, and to restore him to the positions of which that sentence deprived him – such restoration to take effect from the date of his dismissal from the service."

The report found Porter guilty of no wrongdoing during the course of action on August 29, 1862, and, in fact, credited him with saving the Union Army from an even greater defeat, declaring: What General Porter actually did do, although his situation was by no means free from embarrassment and anxiety at the time, now seems to have been only the simple, necessary action which an intelligent soldier had no choice but to take.

The Radical Republicans were organized primarily by Senator John A. Logan,[24] one of Grant's top generals during the Vicksburg campaign, and focused on the illegality of the Schofield Commission and the perceived traitorous nature of Porter.

Once on his death bed, General Porter began working with sculptor James E. Kelly to create a monument that reflected how he viewed his legacy.

[25] Though the obsessive, partisan animosity that gripped much of the country during the trial and subsequent attempts to overturn the verdict have been almost entirely forgotten, the effect of the meticulous casework undertaken by Porter and his allies can be seen at Manassas National Battlefield Park, the site of the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Using Porter's extremely detailed maps, they were able to restore the grounds to within one inch of their previous form and replant to create the most historically accurate battlefield in the park system.