Covenanters

In response to the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Covenanter troops were sent to Ireland, and the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant brought them into the First English Civil War on the side of Parliament.

As the Wars of the Three Kingdoms progressed, many Covenanters came to view English religious Independents like Oliver Cromwell as a greater threat than the Royalists, particularly their opposition to state religion.

The Kirk Party now gained political power, and in 1650, agreed to provide Charles II with Scottish military support to regain the English throne, then crowned him King of Britain in 1651.

[7] Many Scots fought in the Thirty Years' War, one of the most destructive religious conflicts in European history, while there were close economic and cultural links with the Protestant Dutch Republic, then fighting for independence from Catholic Spain.

[9] When a revised Book of Common Prayer was introduced in 1637, it caused anger and widespread rioting across Scotland, perhaps the most famous sparked when Jenny Geddes threw a stool at the minister in St Giles Cathedral.

[10] More recently, historians like Mark Kishlansky have argued she was part of a series of carefully planned and co-ordinated acts of protest, the origin being as much political as it was religious.

[11] Supervised by Archibald Johnston and Alexander Henderson, in February 1638 representatives from all sections of Scottish society agreed to a National Covenant, pledging resistance to liturgical "innovations".

Covenanters believed they were preserving a divinely ordained form of religion which Charles was seeking to alter, although debate as to what exactly that meant persisted until finally settled in 1690.

[14] The Marquess of Argyll and six other members of the Scottish Privy Council had backed the Covenant;[15] Charles tried to impose his authority in the 1639 and 1640 Bishop's Wars, with his defeat leaving the Covenanters in control of Scotland.

[16] When the First English Civil War began in 1642, the Scots remained neutral at first but sent troops to Ulster to support their co-religionists in the Irish Rebellion; the bitterness of this conflict radicalised views in Scotland and Ireland.

[17] Since Calvinists believed a "well-ordered" monarchy was part of God's plan, the Covenanters committed to "defend the king's person and authority with our goods, bodies, and lives".

In December 1647, Charles agreed to impose Presbyterianism in England for three years and suppress the Independents but his refusal to take the Covenant himself split the Covenanters into Engagers and Kirk Party fundamentalists or Whiggamores.

The Terms of Incorporation published on 12 February 1652 made a new Council of Scotland responsible for regulating church affairs and allowed freedom of worship for all Protestant sects.

Robert Lilburne, English military commander in Scotland, used the excuse of Resolutioner church services praying for the success of Glencairn's rising to dissolve both sessions.

[31] He therefore encouraged internal divisions within the Kirk, including appointing Gillespie Principal of the University of Glasgow, against the wishes of the James Guthrie and Warriston-led Protestor majority.

[33] In 1662, the Kirk was restored as the national church, independent sects banned, and all office-holders required to renounce the 1638 Covenant; about a third, or around 270 in total, refused to do so and lost their positions as a result.

[33] Most occurred in the south-west of Scotland, an area particularly strong in its Covenanting sympathies; the practice of holding conventicles outside the formal structure continued, often attracting thousands of worshippers.

[34] The government alternated between persecution and toleration; in 1663, it declared dissenting ministers "seditious persons" and imposed heavy fines on those who failed to attend the parish churches of the "King's curates".

[40] The 1681 Scottish Succession and Test Acts made obedience to the monarch a legal obligation, "regardless of religion", but in return confirmed the primacy of the Kirk "as currently constituted".

[41] A number of government figures, including James Dalrymple, chief legal officer, and Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll, objected to inconsistencies in the Act and refused to swear.

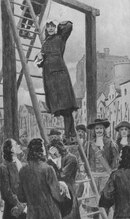

This led to the period known in Protestant historiography as "the Killing Time"; the Scottish Privy Council authorised the extrajudicial execution of any Covenanters caught in arms, policies carried out by troops under John Graham, 1st Viscount Dundee.

[46] Despite his Catholicism, James VII became king in April 1685 with widespread support, largely due to fears of civil war if he were bypassed, and opposition to re-opening past divisions within the Kirk.

Although William wanted to retain bishops, the role played by Covenanters during the Jacobite rising of 1689, including the Cameronians' defence of Dunkeld in August, meant their views prevailed in the political settlement that followed.

[54] Covenanter graves and memorials from the "Killing Time" became important in perpetuating a political message, initially by the small minority of the United Societies who remained outside the Kirk.