Book of Common Prayer

[4] The forms of parish worship in the late mediaeval church in England, which followed the Latin Roman Rite, varied according to local practice.

[citation needed] The work of producing a liturgy in English was largely done by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, starting cautiously in the reign of Henry VIII (1509–1547) and then more radically under his son Edward VI (1547–1553).

It was no mere translation from the Latin, instead making its Protestant character clear by the drastic reduction of the place of saints, compressing what had been the major part into three petitions.

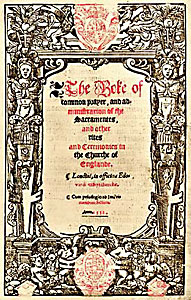

[10] Despite conservative opposition, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity on 21 January 1549, and the newly authorised Book of Common Prayer (BCP) was required to be in use by Whitsunday (Pentecost), 9 June.

Cranmer hoped these would also serve as a daily form of prayer to be used by the laity, thus replacing both the late mediaeval lay observation of the Latin Hours of the Virgin and its English-language equivalent primers.

[31] From the outset, the 1549 book was intended only as a temporary expedient, as German reformer Bucer was assured on meeting Cranmer for the first time in April 1549: "concessions … made both as a respect for antiquity and to the infirmity of the present age", as he wrote.

[45] Consequently, when the accession of Elizabeth I reasserted the dominance of the Reformed Church of England, a significant body of more Protestant believers remained who were nevertheless hostile to the Book of Common Prayer.

[49] Convocation had made its position clear by affirming the traditional doctrine of the Eucharist, the authority of the Pope, and the reservation by divine law to clergy "of handling and defining concerning the things belonging to faith, sacraments, and discipline ecclesiastical.

Cranmer, a good liturgist, was aware that the Eucharist from the mid-second century on had been regarded as the Church's offering to God, but he removed the sacrificial language anyway, whether under pressure or conviction.

"[53] In the meantime, the Scottish and American Prayer Books not only reverted to the 1549 text, but even to the older Roman and Eastern Orthodox pattern by adding the Oblation and an Epiclesis – i.e. the congregation offers itself in union with Christ at the Consecration and receives Him in Communion – while retaining the Calvinist notions of "may be for us" rather than "become" and the emphasis on "bless and sanctify us" (the tension between the Catholic stress on objective Real Presence and Protestant subjective worthiness of the communicant).

However, these Rites asserted a kind of Virtualism in regard to the Real Presence while making the Eucharist a material sacrifice because of the oblation,[54] and the retention of "may be for us the Body and Blood of thy Savior" rather than "become" thus eschewing any suggestion of a change in the natural substance of bread and wine.

The instruction to the congregation to kneel when receiving communion was retained, but the Black Rubric (#29 in the Forty-Two Articles of Faith, which were later reduced to 39) which denied any "real and essential presence" of Christ's flesh and blood, was removed to "conciliate traditionalists" and aligned with the Queen's sensibilities.

Very high attendance at festivals was the order of the day in many parishes and in some, regular communion was very popular; in other places families stayed away or sent "a servant to be the liturgical representative of their household.

Griffith Thomas commented that the retention of the words "militant here in earth" defines the scope of this petition: we pray for ourselves, we thank God for them, and adduces collateral evidence to this end.

This now declared that kneeling in order to receive communion did not imply adoration of the species of the Eucharist nor "to any Corporal Presence of Christ's natural Flesh and Blood"—which, according to the rubric, were in heaven, not here.

The illegal use of elements of the Roman rite, the use of candles, vestments and incense – practices collectively known as Ritualism – had become widespread and led to the establishment of a new system of discipline, intending to bring the "Romanisers" into conformity, through the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874.

[83] The Act had no effect on illegal practices: five clergy were imprisoned for contempt of court and after the trial of the much loved Bishop Edward King of Lincoln, it became clear that some revision of the liturgy had to be embarked upon.

After the communists took over mainland China, the Diocese of Hong Kong and Macao became independent of the Chung Hua Sheng Kung Hui, and continued to use the edition issued in Shanghai in 1938 with a revision in 1959.

Its liturgy, from the first, combined the free use of Cranmer's language with an adherence to the principles of congregational participation and the centrality of the Eucharist, much in line with the Liturgical Movement.

A finished, fully revised Book of Common Prayer for use in the Church in Wales was authorised in 1984, written in traditional English, after a suggestion for a modern language Eucharist received a lukewarm reception.

The translated 1662 BCP has commonly been called Te Rawiri ("the David"), reflecting the prominence of the Psalter in the services of Morning and Evening Prayer, as the Māori often looked for words to be attributed to a person of authority.

The AAPB sought to adhere to the principle that, where the liturgical committee could not agree on a formulation, the words or expressions of the Book of Common Prayer were to be used,[106] if in a modern idiom.

Numerous objections were made and the notably conservative evangelical Diocese of Sydney drew attention both to the loss of BCP wording and of an explicit "biblical doctrine of substitutionary atonement".

The Book of Common Prayer has also been translated into these North American indigenous languages: Cowitchan, Cree, Haida, Ntlakyapamuk, Slavey, Eskimo-Aleut, Dakota, Delaware, Mohawk, Ojibwe.

[112] Joseph Gilfillan was the chief editor of the 1911 Ojibwa edition of the Book of Common Prayer entitled Iu Wejibuewisi Mamawi Anamiawini Mazinaigun (Iw Wejibwewizi Maamawi-anami'aawini Mazina'igan).

Lewis..."[120] According to Robert Duncan, the first archbishop of the ACNA, "The 2019 edition takes what was good from the modern liturgical renewal movement and also recovers what had been lost from the tradition.

John Wesley, an Anglican priest whose revivalist preaching led to the creation of Methodism wrote in his preface to The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America (1784), "I believe there is no Liturgy in the world, either in ancient or modern language, which breathes more of a solid, scriptural, rational piety than the Common Prayer of the Church of England.

… Therefore if any man can shew any just cause, why they may not lawfully be joined together, let him now speak, or else hereafter for ever hold his peace … Blessed Lord, who hast caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant that we may in such wise hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and comfort of thy holy Word, we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which thou hast given us in our Saviour Jesus Christ.

In addition, there are a small number of direct allusions to liturgical texts in the Prayer Book; e.g. Henry VIII 3:2 where Wolsey states "Vain Pomp and Glory of this World, I hate ye!

The primary function for Cambridge University Press in its role as King's Printer is preserving the integrity of the text, continuing a long-standing tradition and reputation for textual scholarship and accuracy of printing.